S'pore sets sights on being regional centre for clinical trials, from diabetes to cancer

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

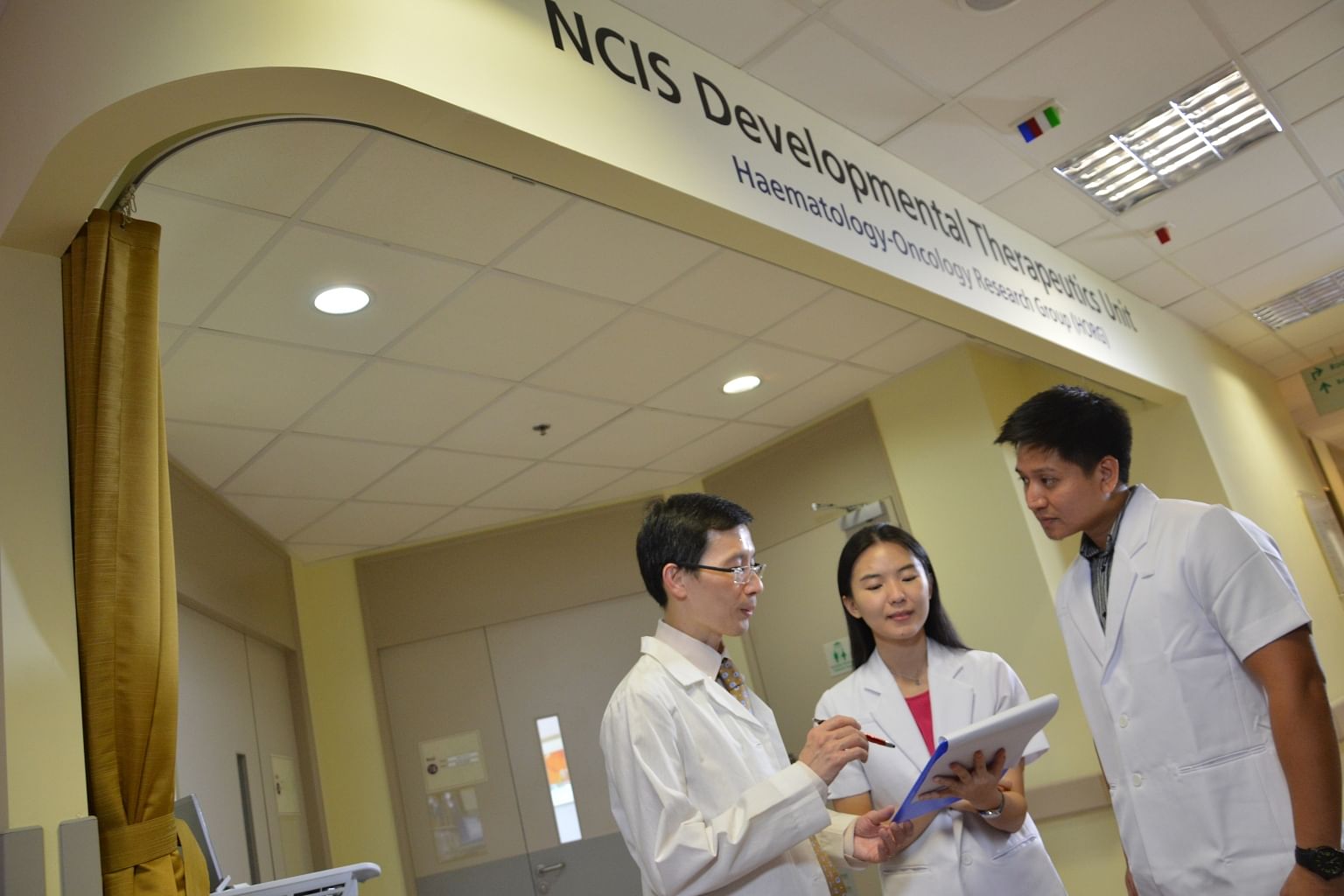

Associate Professor David Tan is a senior consultant at the haematology-oncology department in NCIS.

PHOTO: NATIONAL UNIVERSITY CANCER INSTITUTE SINGAPORE

SINGAPORE - Singapore has set its sights on becoming a regional centre for clinical trials as these will give Singaporeans early access to new treatments and drugs.

In view of World Clinical Trials Day last Friday, The Straits Times looks at three different trials and explores how the nature of clinical trials has changed over the years.

World Clinical Trials Day was started to recognise the work done by Scottish doctor James Lind on May 20, 1747, when he started what is often considered the first randomised clinical trial aboard a ship.

How clinical trials have changed

Clinical trials, which are the bedrock of modern medicine, have changed significantly over the years.

"Trials need not involve drug interventions. For example, trials can involve the follow-up of groups of individuals with specific characteristics to better understand the factors that contribute to development of disease," Dr Sue-Anne Toh, an adjunct associate professor of medicine at the National University of Singapore, told ST in an exclusive interview.

"From there, we can potentially learn about how we can enhance interventions, whether they be medications or specific lifestyle changes, to alter the course of progression to disease or complications," said Dr Toh, who is also leading some clinical trials on diabetes at the National University Hospital.

Such observational trials likely involve healthy participants too and are not limited to people with or at risk of disease.

With technology, the manner in which trials can be conducted has also evolved, and they no longer necessarily involve a face-to-face meeting. Instead, they can be conducted through virtual platforms, polls and structured questionnaires, and they can be a mix of all these different modes, Dr Toh added.

Finally, a globally connected world has also facilitated multicentred trials, where participant profiles can come from different geographical locations.

Diabetes: Progression of disease in Asian population

Dr Toh and her team conducted one of the world's largest comprehensive scientific studies on the progression to diabetes in Asian populations. The three-year study ended at the start of this year.

Type 2 diabetes is an increasing epidemic in the region, and it is projected that its prevalence in Singapore's population will double from 7.3 per cent in 1990 to 15 per cent in 2050. The total economic cost of the disease alone is expected to increase by 2.4 fold.

In the West, where there is a higher prevalence of obesity, there is a stronger correlation between weight loss and a reduced risk of developing diabetes. However, this is not necessarily true in the Asian context, Dr Toh said.

"We may be lean and even underweight and yet have diabetes. And there may be certain aspects of biology that are different in us compared with Caucasians and telling these thin people to lose weight is not helpful. In fact, it can be demoralising," she said.

"But with this study, we will have our own local data that is relevant to the Asia-Pacific region, which will help contribute to our understanding of what other factors - be they biological, environmental or lifestyle - also contribute to the progression of diabetes in our population."

The study involved 1,679 Singaporeans with pre-diabetes or normal blood glucose levels.

It was found that having an impaired ability to secrete insulin was a landmark feature of those with pre-diabetes.

"We know that type 2 diabetes occurs when the body cannot respond well to the actions of insulin (insulin resistance), and the pancreas cannot make enough insulin to keep glucose levels within normal range. However, the exact contribution of each defect and the timing at which it occurs in the progression of diabetes is incompletely understood, especially in Asians," Dr Toh said.

"Our study has shown that in the Singapore population, those with pre-diabetes have mild insulin resistance but a disproportionately greater inability to produce enough insulin. Our findings provide important insights into the main factors that drive the development of abnormal glucose levels in Asians."

"This suggests that interventions that focus on not overworking the pancreas could be particularly effective in lowering the risk of type 2 diabetes in Asians," Dr Toh added.

ccpatient - Tang Wen You, a manager in her 30s, participated in the APT-2D study to monitor her blood sugar levels once every 6 months over three years from 2018 to 2021. Photo taken on 16 May, 2022.

PHOTO: ST

A study participant, who wanted to be known only as Ms Tang, was glad that she volunteered. It was through this study that Ms Tang, a manager in her 30s, found out she had pre-diabetes.

She knew of the study through an e-mail that was sent to all employees at her previous workplace.

"It was my first time participating in a clinical trial, and the process was generally smooth," she said.

The study team closely monitored her blood sugar levels once every six months over three years - from 2018 to last year.

"As I am of a healthy weight and generally do not consume food that is too unhealthy, I did not think that I'd have pre-diabetes," she added.

Ms Tang, who was sedentary in the past, now puts in effort to incorporate some physical activity, such as Zumba classes or brisk walking, into her daily routine to keep her glucose levels in check.

Costly cancer drugs: Looking at reducing doses

Newer cancer drugs have come with increasingly higher costs, making it harder for those who need treatment to gain access to them.

"In Asia, cancer diagnosis can be catastrophic for households who are unable to afford it. Though some of these costs are borne by insurance and the Government, there needs to be a way for these costs to be optimised," said Professor Goh Boon Cher, deputy director of research at the National University Cancer Institute, Singapore.

One way is to relook the dose of the drug given, he added.

In a rush for a drug to get registered, it is sometimes given at higher doses in the hope that this will lead to a better outcome.

The same result can actually be obtained with a lower dose, but this option is not tested as the trial may not have been as extensive, Prof Goh said.

One example is epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutant lung cancer, where a mutation in the gene for EGFR can make it grow too much, leading to cancer.

This particular mutation occurs in more than 40 per cent of tumours in Singaporean lung cancer patients.

The drug to treat this cancer costs about $8,500 a month.

After examining the pharmacology of the drug, Prof Goh and his team started a trial to recruit 60 patients to find out if halving the dose would achieve the same clinical benefits.

However, funding is a stumbling block. Conventionally, trials are funded by pharmaceutical companies, but such a trial would hold little incentive for them, given an erosion of profits should the dose be halved.

"We, hence, turn to philanthropy," Prof Goh said.

"Our trial remains underfunded at this stage, but such trials are hugely beneficial to patients - they are able to pay less for the same outcome and potentially experience fewer side effects."

Additionally, patients can take part in more than one trial, and there should not be a misconception that the elderly cannot participate in trials, Prof Goh added.

Madam Hee Poh Lian, 83, who has nasopharyngeal cancer, is one example.

Her first clinical trial experience was an immunotherapy trial, which she started after completing a round of chemotherapy treatment. Her second clinical trial was an oral chemotherapy type.

"The process has been smooth and the staff have been nice. They calmed me down and always made sure to check on me," said Madam Hee, whose condition has improved after both trials.

Infections: 'Trojan horse' trial to fight antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance is a common problem in infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections and wound or surgical site infections.

This is especially so as all antibiotics that are currently used to treat these infections belong to the same class and have similar modes of action.

However, the discovery of Cefiderocol, a new antibiotic with a Trojan horse mechanism that acts on these infections, has proved to be a game changer, said Associate Professor David Lye, director at the Infectious Disease Research and Training Office in the National Centre for Infectious Diseases.

A Trojan horse refers to any kind of deception that involves getting a target (the bacteria) to willingly allow an enemy (the antibiotic) into a secure place (the cell of the bacteria).

Cefiderocol acts on the channel that transports potassium across the cell membrane.

Potassium is a salt that is important to the cell's function.

Cefiderocol enters the bacteria through the potassium channel and kills the bacteria once it is inside, Prof Lye said.

Traditionally, antibiotics destroy the integrity of the bacterial membranes and cause the cells to burst.

However, some of these bacteria soon adopt a unique structure of their outer membrane, preventing certain drugs and antibiotics from entering the cell, resulting in resistance.

A clinical trial on Cefiderocol, aptly named Gamechanger, investigates this new mode of action.

The trial is led by Professor David Paterson, director at The University of Queensland Centre for Clinical Research.

Retiree Ang Hwee Kheng, 55, who was recruited to be part of the trial earlier this month when he was hospitalised as bacteria was detected in his blood, said the trial process has been smooth so far.

"I wanted to join the trial to contribute to medicine so that better care can be given to others in the future," said Mr Ang, whose doctor had recommended that he joined the trial.

Mr Ang takes the antibiotic via an intravenous drip and does not have to pay for medical tests or antibiotics as they are funded by the trial.

Ongoing study

Nurture (NUh Repository of TissUe and data for Research in Endocrinology) is the National University Hospital's (NUH) initiative to build a secure biorepository of tissue and health records data for research in the National University Health System. This provides resources to investigators in diabetes-related studies ranging from genetics and diagnosis to diets/lifestyles and clinical care treatment.

Those who want to be part of the study can call 9072- 4185 or 9071-9782 during office hours or send an e-mail to NUH_nurture@nuhs.edu.sg