S'pore scientist finds way to extract collagen from fish skin for bone regeneration, wound healing

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

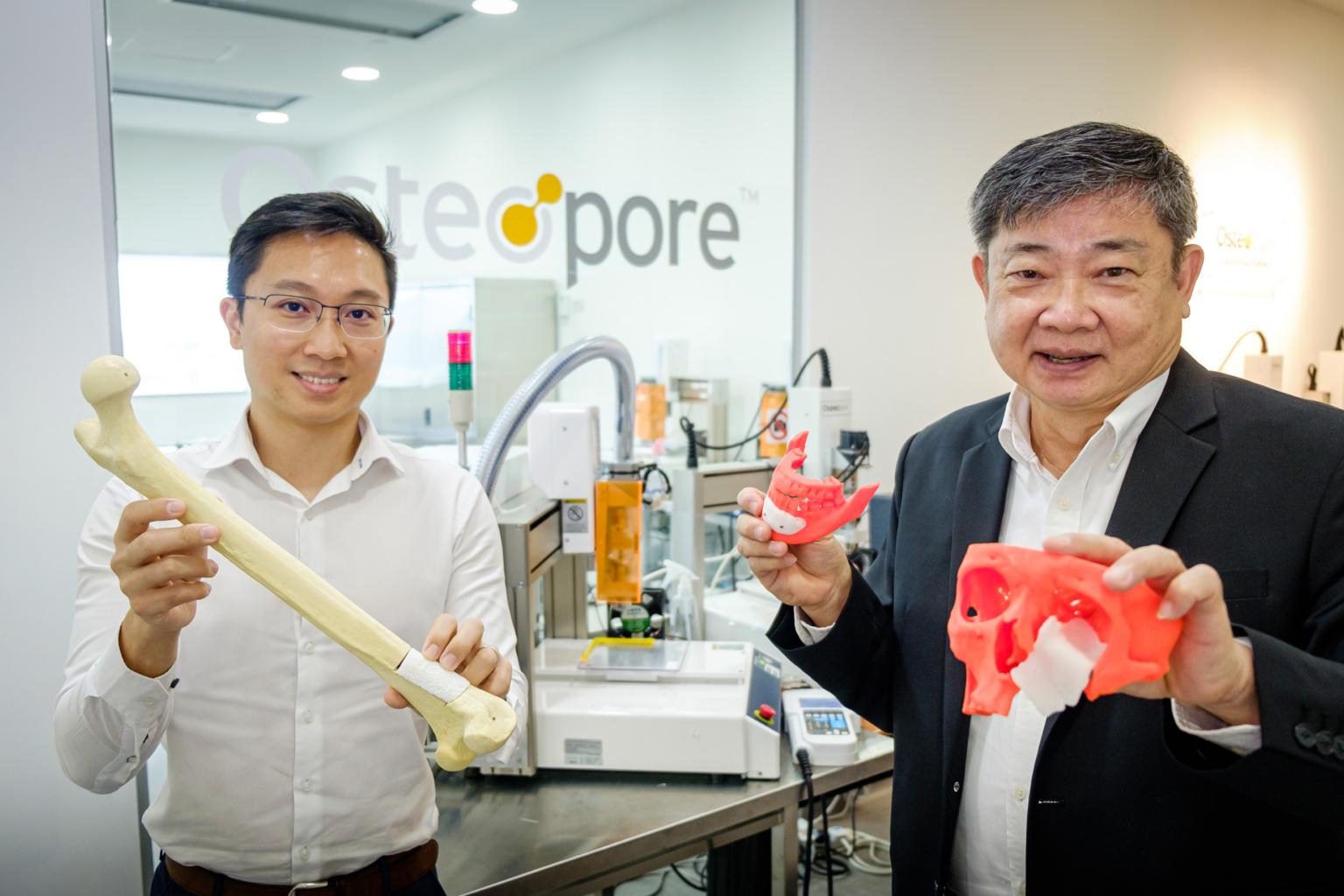

Osteopore's chief technology officer Lim Jing (left) and Osteropore co-founder Teoh Swee Hin with 3D-printed bone implant samples.

PHOTO: NANYANG TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY

SINGAPORE - While discarded fish skin may seem unappealing to many, one scientist here is fishing for ways to unlock its potential for wound healing and bone regeneration.

Fish skin is a rich source of collagen - a natural material that is abundant in the skin - which promotes the regeneration of skin, bone and cartilage.

"In Brazil, the skin of tilapia fish has been used on burn victims. They wash it, sterilise it and wrap it around the wound area. The result is that the skin grows back without much observable scarring," said Professor Teoh Swee Hin, who recently retired from Nanyang Technological University (NTU) and has been looking into the potential of fish skin in medical use for the past three to four years.

Scientists believe that there are important ingredients in marine collagen found in fish skin, said Prof Teoh, 67, who was the president's chair in Chemical and Biomedical Engineering at NTU until he retired in February this year.

In 2017, Brazilian researchers began experimenting with the use of this unorthodox method to ease the pain of burn victims while aiming to cut medical costs.

In the past, frozen pig skin and human tissue were used to allow the transfer of collagen - but the lack of these supplies in Brazil prompted researchers to look for alternative sources.

"Fish skin is a sustainable source of collagen, as discarded fish parts account for around 70 per cent to 85 per cent of the catch from fishing and aquaculture industries," he added.

When used in bone regeneration, collagen acts as a glue for bone cells to attach to it, proliferate and grow.

"This can help to shorten the recovery process after bone implant surgery," said Prof Teoh.

The healing time post-implant usually takes at least three months.

In a research study published last month in the journal Current Opinion In Biotechnology, Prof Teoh showed the viability of extracting collagen from tilapia skin - a fish that is readily available from local farms.

The collagen has also been successfully fabricated into the scaffolds needed for surgical implants, though more studies will be needed to determine the long-term cellular and tissue response when used in the human body.

Prof Teoh was a pioneer in 3D-printed implants for biomedical use in the 1980s.

The 3D printing allows implants to be customised to each patient's needs. The implants' porous structure also enables them to trap the patients' own cells and promote the growth and regeneration of new tissue.

However, aside from being able to replace injured or diseased bone, Prof Teoh's implants have an added benefit. They are biodegradable, meaning that they gradually break down over 18 to 24 months, while serving as a scaffold for new bone to grow onto.

"It's like when we're constructing a tall building, we need a scaffold so the architecture can be properly installed," he added.

These implants are made primarily from a material known as polycaprolactone (PCL), a type of biodegradable polymer that has been used in tissue engineering and surgical implants.

While other polymeric implants can produce toxic by-products when they break down in the body, PCL has only two - carbon dioxide and water - which are the body's natural by-products.

In 2003, he co-founded a start-up, Osteopore International, that commercialised such implants. They have benefited some 50,000 patients worldwide to date.

But PCL forms only a very basic structure for the implants, and more can be done to nourish the bone and help support its growth, said Prof Teoh.

He has worked with Dr Lim Jing, who is Osteopore's chief technology officer, to incorporate tricalcium phosphate - a natural mineral found in bone that gives it its density - into the implants.

Dr Lim has also studied the possibility of infusing minerals like magnesium into the bone implants, which can then be released to nourish the surrounding bones and tissue once the implant has fully degraded.

Said Prof Teoh: "We are constantly innovating, but while doing so, it is also important to consider the environmental, economic and social impact of our work."

"Collagen from fish skin is a sustainable source as it comes entirely from waste in the aquaculture industry. At the same time, we can support fishermen who may be facing falling incomes as they struggle to catch enough fish - especially in Singapore and Malaysia, where competition is tough with big fish trawlers," he added.

Being able to process fish skin for sale can help make a difference in their income, he added.

Above all, he hopes that there will soon be commercial interest in extracting and producing fish collagen at scale for biomedical use or in regenerative medicine.

"This is especially because Singapore encourages land-based fish farming where the feedstock is controlled and free from antibiotics, making it a plus for collagen extraction as there is good traceability. In addition, the collagen would also be of high quality and purity," said Prof Teoh, who is hoping to continue his research into fish collagen.