Social workers say the system failed to protect Megan Khung; pre-school not solely responsible

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Megan Khung was abused by her mother Foo Li Ping and the woman's then boyfriend Wong Shi Xiang for months before she died.

PHOTO: INSTAGRAM

SINGAPORE – It was a collective failure of the system that led to the unfortunate demise of four-year-old Megan Khung, said the Singapore Children’s Society and other social workers on April 9.

While there might have been shortcomings in terms of how the pre-school had surfaced its concerns, Megan’s teachers had been “very quick” to pick up on the physical signs of abuse when it first started, the society said in a statement.

Its remarks came a day after the authorities laid out the sequence of events that took place before Megan died in February 2020, saying that Beyond Social Services – which runs the pre-school she attended – did not “fully describe the severity” of her injuries.

The girl had been abused by her mother Foo Li Ping and the woman’s then boyfriend Wong Shi Xiang for months before Wong inflicted a fatal punch on the girl.

The Children’s Society noted that the pre-school and Beyond had tried multiple times to raise their concerns to the relevant agencies, like the Early Childhood Development Agency (ECDA) and a child protection specialist centre, to seek their advice on managing the case.

Beyond also assisted Megan’s grandmother with lodging a police report. The Straits Times has reached out to the police for more details on how they followed up after the report was made.

While pre-school educators have a vantage point for keeping an eye on the well-being of children and spotting signs of suspected abuse, their primary training and duty is in nurturing and teaching, a spokesman for the Children’s Society said.

Teachers need to be supported to know how to manage suspected abuse concerns and escalate them appropriately, he said.

A social worker who works at an agency that helps disadvantaged children said on condition of anonymity that she felt it was unfair for Beyond to shoulder the blame.

“They did what they could, with what information and resources they had. Social workers are not in this line of work for money or fame, we do this because we care. I can imagine that the Beyond workers in this case tried their best,” said the 29-year-old.

“The larger system could have done better in protecting her. It took her death for protocols to be enhanced,” she added.

Ms Lin Shiyun, founder of 3Pumpkins, a non-profit group that works with children, said there is a need to look at the different layers of the child safeguarding ecosystem and see which areas have to be improved.

“For those who interact with the children most regularly, like the teachers or community workers, they need training and resources for child safeguarding work.

“For the child protection services, there needs to be a review of their ability to follow up with cases as the speed of their actions is usually very dependent on how effectively the community escalates the situation,” she said.

“It shouldn’t be the onus of the party reporting to know which exact button to push to get the right resources,” she added.

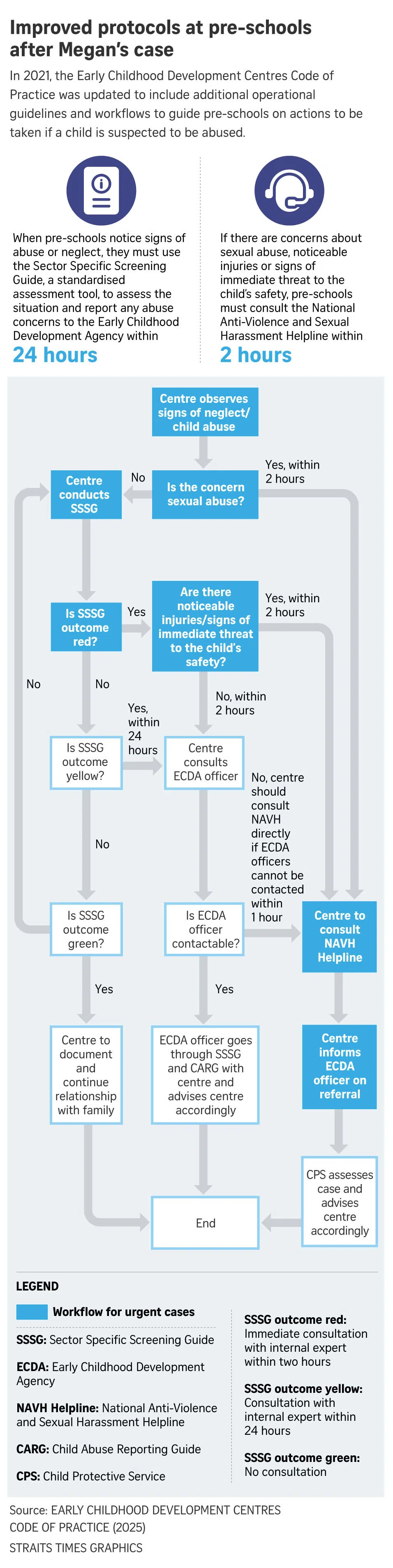

In 2021, guidelines were introduced so that pre-schools know the specific actions to take if a child is suspected to be a victim of abuse. They are required to assess the situation and report any child abuse concerns to ECDA within 24 hours.

If a child with such concerns has been regularly absent or is withdrawn from pre-school without valid reasons, the pre-school is also required to inform the social worker or the Ministry of Social and Family Development’s (MSF) child protection officer working with the child.

Touch Community Services’ chief executive James Tan told ST that the case has deeply shaken many in the organisation, and has deepened the agency’s commitment to not look away when any signs of abuse are spotted. Like Beyond, Touch runs childcare centres.

“We want to partner with community first responders – residents, schools and neighbourhood shops and volunteers – to build awareness of early warning signs of abuse; offer spaces for honest conversations about child safety and community care; and make it easier for anyone to reach out, and to know how to do so if they are worried about someone they know,” he said.

Children’s Aid Society director of home Cindy Tay said in a LinkedIn post on April 8 that when such incidents occur, the responsibility typically falls on the entire system, not just one person or one agency.

The approach of singling out one social service agency can undermine the relationships and trust between community agencies, potentially hindering collaborative efforts for years to come, she said.

“It may also lead community workers to feel hesitant to take necessary actions or make decisions, fearing that any errors could result in public criticism.”

Over the last 10 years, there have been at least eight cases that were not known to social services when the child was killed, MSF had said.

One of the recommendations by the Children’s Society is for ECDA to appoint child safety officers to manage child protection concerns within each pre-school centre.

These officers can be educators who step up to receive dedicated and specialised training in child protection, including knowledge of how to utilise the Sector-Specific Screening Guide, the society’s spokesman said.

The guide was rolled out by MSF in 2016 to guide front-line professionals in handling child abuse concerns.

“However, the availability of the tool does not necessarily mean that it is effectively disseminated and utilised in the sector,” the Children’s Society’s spokesman said.

He added that in 2017, a survey the society conducted to understand the knowledge of pre-school educators in managing suspected child abuse and neglect concerns found that only 27.1 per cent of 336 respondents were aware of the guide.

The society is now conducting a follow-up survey to find out if there has been any change in awareness since then.