Slightly fewer people recorded sleeping rough in 2025; new fund launched to trial solutions

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

A new $450,000 fund will provide grants for organisations to trial solutions that address the underlying causes of rough sleeping.

PHOTO: ST FILE

- Singapore's street count in 2025 found 496 rough sleepers, a 6 per cent decrease from 530 in 2022.

- A new $450,000 Fund will provide grants to organisations to come up with ideas to aid rough sleepers with housing, medical, psychological, and social support.

- Many rough sleepers have housing options but cite family conflicts or personal preference as reasons for sleeping rough, highlighting complex relational issues.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – The number of people who spend the night on Singapore’s streets has dipped by 6 per cent, from 530 in 2022 to 496 in 2025, according to a Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) report released on Jan 9.

To strengthen support for this group, MSF announced a new $450,000 fund that would provide grants for organisations to trial solutions that address the underlying causes of rough sleeping.

It will also redesign units at two transitional shelters in Yio Chu Kang and Jalan Kukoh to improve privacy and provide more storage space for residents, with the aim of improving the take-up rate for these spaces.

The ministry conducted a nationwide street count of rough sleepers on July 18, 2025, building on the data from its previous street count done in 2022. Earlier counts had been carried out by the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in 2019 and 2021.

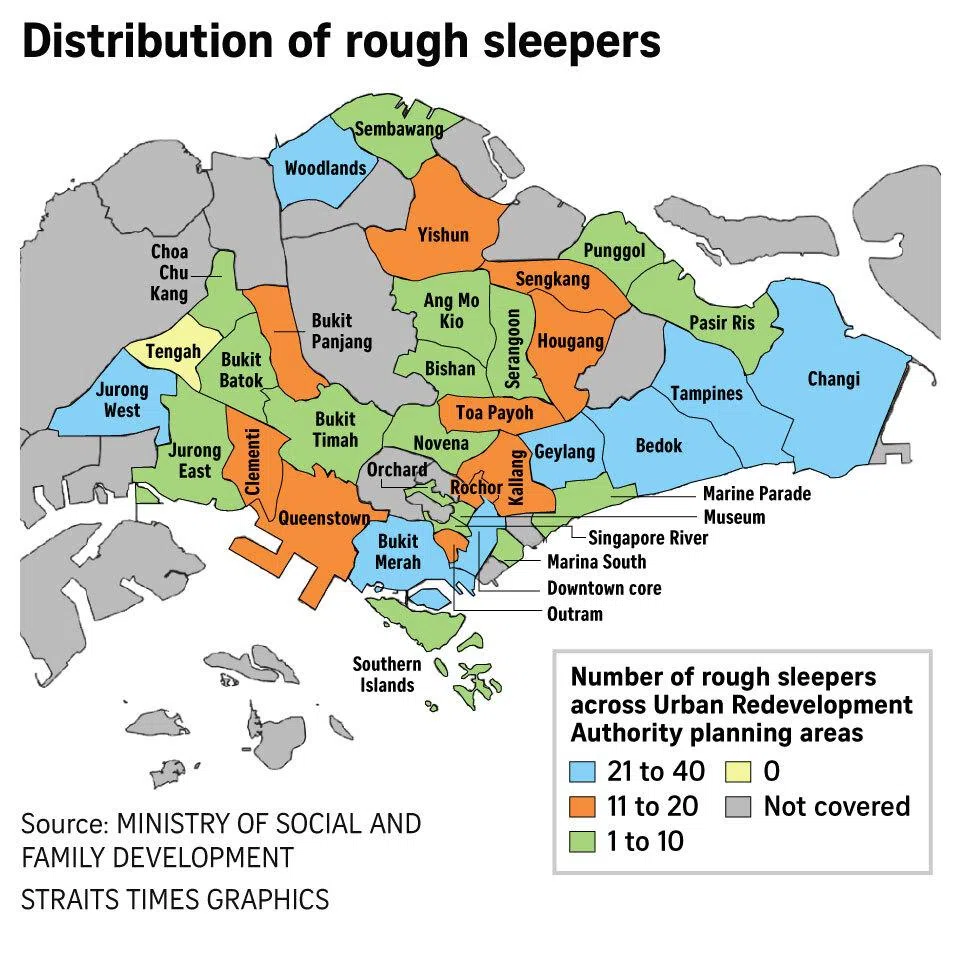

In 2025, the highest number of rough sleepers was found in Bukit Merah, Jurong West and Bedok.

The demographics of those found sleeping rough were similar to those of 2022, with about 85 per cent male and more than half aged above 50. About half were Chinese, while Malays and Indians each made up about 20 per cent of this population.

Most slept near HDB blocks and in sheltered and well-lit places such as parks and commercial areas like malls and offices, which was similar to 2022’s findings.

Volunteers then carried out a survey that involved 128 rough sleepers, or about a quarter of the number sighted during the street count.

About two-thirds of those surveyed were in some form of employment, with 35 per cent working full-time and 20 per cent working part-time. A large majority of those working earned less than $2,000 a month.

About three-quarters of the respondents had been sleeping in public spaces for more than a year, and almost all regularly slept in the same location.

Nearly half of those surveyed were sleeping rough despite having alternative housing options, and the main reason they cited was relationship breakdowns. Around 17 per cent had a public rental flat, 16 per cent had a purchased property, while another 15 per cent had a relative’s, friend’s or open market rental home they could return to.

Disagreements with family, friends or cohabitants were the most cited reason for sleeping rough, followed by problems securing housing and financial issues.

Close to a third of respondents cited multiple reasons for sleeping rough, which highlighted the complex personal circumstances that make sleeping at home difficult, said the ministry.

One rough sleeper, known as Mr J in the report, started sleeping rough in 2024 due to conflicts with his family. He moved out of the home after his family refused to forgive him after a heated argument, despite his attempt at making amends.

Due to an unstable income, he could not afford hostel accommodation or a private rented room, and chose to sleep rough. He refused shelter support as he saw rough sleeping as a way to make amends for causing the family conflicts, and slept in public for nearly a year before finding alternative housing arrangements.

“Similar to Mr J’s experience, some rough sleepers may take longer to find or accept a solution,” said the report. “Nevertheless, assistance remains available whenever they are ready to seek help.”

The survey also found that eight in 10 had never stayed in a shelter, while 75 per cent of respondents were unreceptive to doing so. Among those who had stayed in a shelter before, the majority were not willing to stay in a shelter or residential home again.

Respondents said the top factor that would encourage them to stay in a shelter was the availability of personal and private space, followed by better locations and more flexible rules on shelter entry and exit.

MSF said these findings could inform the design of new shelters, even as current ones are being enhanced to provide greater personal privacy to encourage rough sleepers to take up shelter support. About two-thirds of the 730 beds in Singapore’s seven transitional shelters are currently occupied.

As at September 2025, there were about 240 individuals and 120 families across the seven shelters here. MSF said individuals stayed at these transitional shelters for an average of 10 months.

Factors that would encourage rough sleepers to stay in a shelter include the availability of personal and private space.

ST PHOTO: KUA CHEE SIONG

Senior Parliamentary Secretary for Social and Family Development Eric Chua told reporters on Jan 7 that rough sleepers face a complex mix of issues, and that the Government will continue to work with partners on the ground, academia, social service agencies and community groups to help.

Volunteers and officers reaching out to rough sleepers must have a relationship with them to better understand their circumstances and render help, he said. “Just as their presenting issues are relational in nature, the solution then is also one that is relational.”

Senior Parliamentary Secretary for Social and Family Development Eric Chua (left) at transitional shelter Transit Point@Yio Chu Kang on Jan 7.

ST PHOTO: KUA CHEE SIONG

When asked about young people sleeping rough, Mr Chua said a deeper dive into the issue is needed.

The proportion of rough sleepers aged 30 and below rose from 3 per cent in 2022 to 6 per cent in 2025, and some community groups said they have seen a rise in the number of young rough sleepers seeking help

MSF said, in response to queries, that young people tended to exhibit different rough sleeping behaviours like couchsurfing instead of sleeping rough on the streets, and the ministry recognised that the street count findings may not fully reflect the state of youth homelessness.

“Although it is not a big number, we do think there are nuances that we need to further unpack, so we are looking for youth agencies to do that,” Mr Chua said.