Singapore's microbial data added to the global atlas of microbes

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The team of around 30 scientists from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research collecting samples around Singapore in 2017.

PHOTO: A*STAR

SINGAPORE - To understand the diversity of life that is invisible to the naked eye, scientists have been collecting samples of microorganisms in cities around the world.

A team of around 30 scientists from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research's (A*Star) Genome Institute of Singapore has been collaborating with scientists in 60 cities, such as Paris and New York, to collect samples from public spots like subways, benches and parks to build a global atlas of microorganisms.

More than 4,700 samples, collected over three years, have been analysed so far. And from these, over 10,000 viruses and 1,000 bacteria have been newly identified.

Over 100 samples were collected from around Singapore, from frequent touch points islandwide such as traffic light buttons and surfaces outside MRT stations, at bus stops and in local parks.

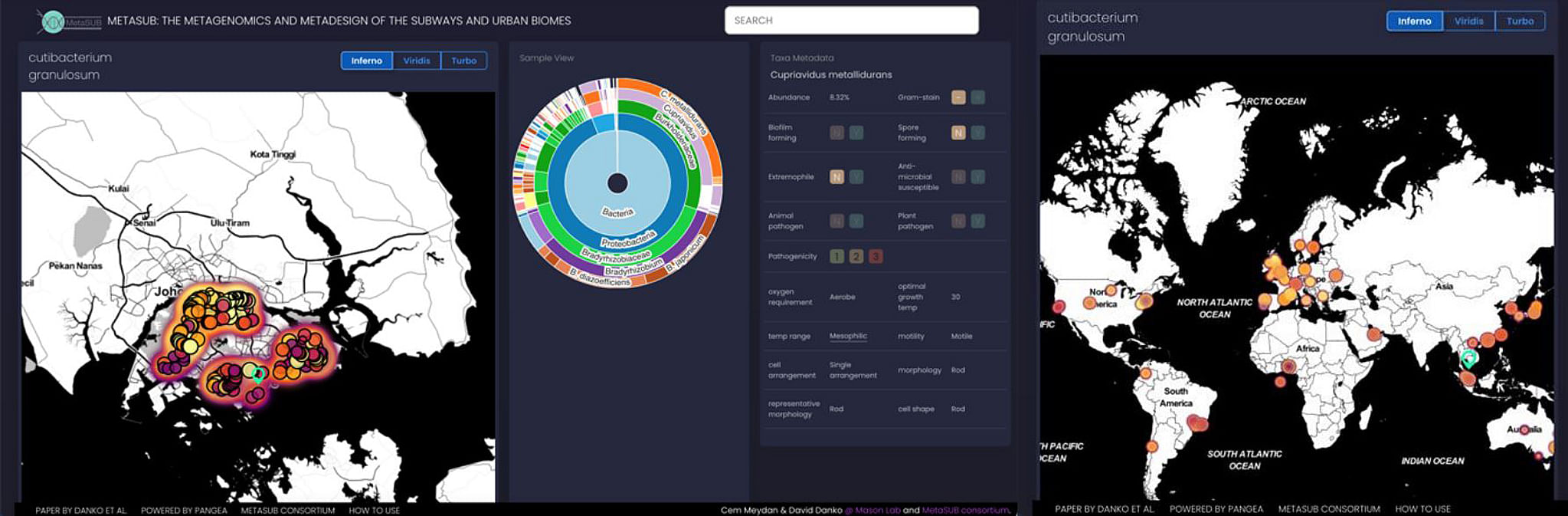

The work was part of an international project known as MetaSub (Metagenomics and Metadesign of the Subways and Urban Biomes), and the study findings were published on May 27 in the scientific journal Cell.

Professor Niranjan Nagarajan, who was the principal investigator of the Singapore arm of the project, told The Straits Times that the global study showed that each city had its own unique microbial fingerprint, and any sample from the city can be identified with nearly 90 per cent accuracy on average.

Each city's unique and endemic microbes are a "biodiversity resource" that can be associated with its geographical location, elevation, average temperature and other environmental characteristics, said Prof Nagarajan.

This can inform researchers on the kind of microbes that people are exposed to, and more can be done to "manipulate these lifeforms" to create new organisms, or give them new capabilities, he added.

In Singapore, 10 key microbes were identified from all the samples, the majority of which were bacteria and are not harmful to humans.

Examples of these include a nitrogen-fixing bacterium known as the Mesorhizobium sp. WSM1497 which is found in plants. It helps to convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form that can be used by plants.

Other types of organisms also include a virus species known as Synechococcus phage S-PM2 which infects photosynthetic bacteria, thus increasing their light-harvesting capacity.

Prof Nagarajan said that little is known about these microorganisms as yet, with more research needed to understand them and what they could potentially do.

One of the 10 key microbes, the Klebsiella quasipneumoniae usually found in both animals and humans, was discovered to have caused hospital-acquired infections such as sepsis, said Prof Nagarajan.

This is a type of blood infection which could trigger widespread inflammation and lead to organ damage.

Other notable observations from Singapore include that the microbes have a moderate diversity of antimicrobial resistance genes - meaning that many of these microbes, which are primarily bacteria, could be resistant to some of the drugs that are usually used to treat infections.

ctnmicrobes07 - Screengrab. Singapore on the world microbial map. The pie chart depicts the different microbes that were found in each sample at a particular location. Credit: A*star

PHOTO: A*STAR

Singapore also has limited viral diversity compared with other travel hubs in the world, he noted, though he added that it is not yet clear why.

The MetaSub project will continue to build on these findings to refine its global microbial map, with the next Global Sampling Day taking place on June 21.

This is a synchronised event, taking place for the fifth year running, with scientists in cities around the world collecting samples from public spaces to build on the global microbial database.