Singapore researchers develop material able to reduce heat in personal protective gear

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Assistant Professor Tan Swee Ching's concern about heat stress grew when he realised healthcare workers endured a felt temperature of about 64 deg C when donning personal protective equipment at room temperature.

SINGAPORE - While most people resign themselves to sweating it out in the tropics, a professor returning to Singapore after seven years abroad in cooler climates was spurred to develop a material that could battle the heat.

When Assistant Professor Tan Swee Ching at the National University of Singapore (NUS) came back in 2014 from his last stop Hong Kong, he found he was no longer acclimatised to the heat and humidity here.

"I thought to myself, if only we had something to reduce relative humidity, we will not need to turn on the air-conditioner," said the researcher from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering.

High amounts of moisture in the air, or humidity, on tropical islands such as Singapore make it harder for sweat to evaporate, thus making temperatures feel hotter than they are.

Prof Tan's concern about heat stress grew as the Covid-19 pandemic hit and he realised that healthcare workers endured a felt temperature of about 64 deg C when donning personal protective equipment at room temperature.

Citing a 2020 study, he noted that such suits often caused these workers to experience thermal strain, leading to exhaustion and dizziness.

So he led a team of NUS researchers to develop a composite film that lowers felt temperatures to 40 deg C in protective suits by enhancing sweat evaporation.

Through trial and error over about eight months last year, the team created a non-toxic, moisture-trapping material composed of a metallic salt, rubber and several other chemicals.

To test the feasibility of applying the composite film in clothing, Home Team Science and Technology Agency (HTX) scientists helped incorporate the film in a protective suit and tested its efficacy with a manikin that can move and simulate human sweat.

Through experiments, the researchers found that the suit could reduce humidity at peak performance for at least two hours.

At a media briefing on Thursday (March 24), researchers demonstrated the material's cooling capabilities to increase sweat evaporation within a closed environment.

Reporters experienced what it felt to be inside a suit fitted with the material by comparing the temperature difference between wearing a glove and placing their hand inside a box fitted with the sweat absorbing film.

The material can be dried and reused for a minimum of 30 times, said Prof Tan.

The suit is also highly energy-efficient, compared with other materials, he added.

For example, silicon gel, typically used in food packaging to absorb fluid, can absorb 30 per cent of its own weight in water and needs to be heated to 110 deg C to release the moisture.

In contrast, the composite film can absorb its own weight in moisture and release it when heated in the sun for two hours, or half an hour in the oven at 50 deg C.

Assistant Professor Tan Swee Ching (centre) and Dr Saravana Kumar (right) testing a sheet of the moisture-trapping film in a climatic chamber.

PHOTO: ST

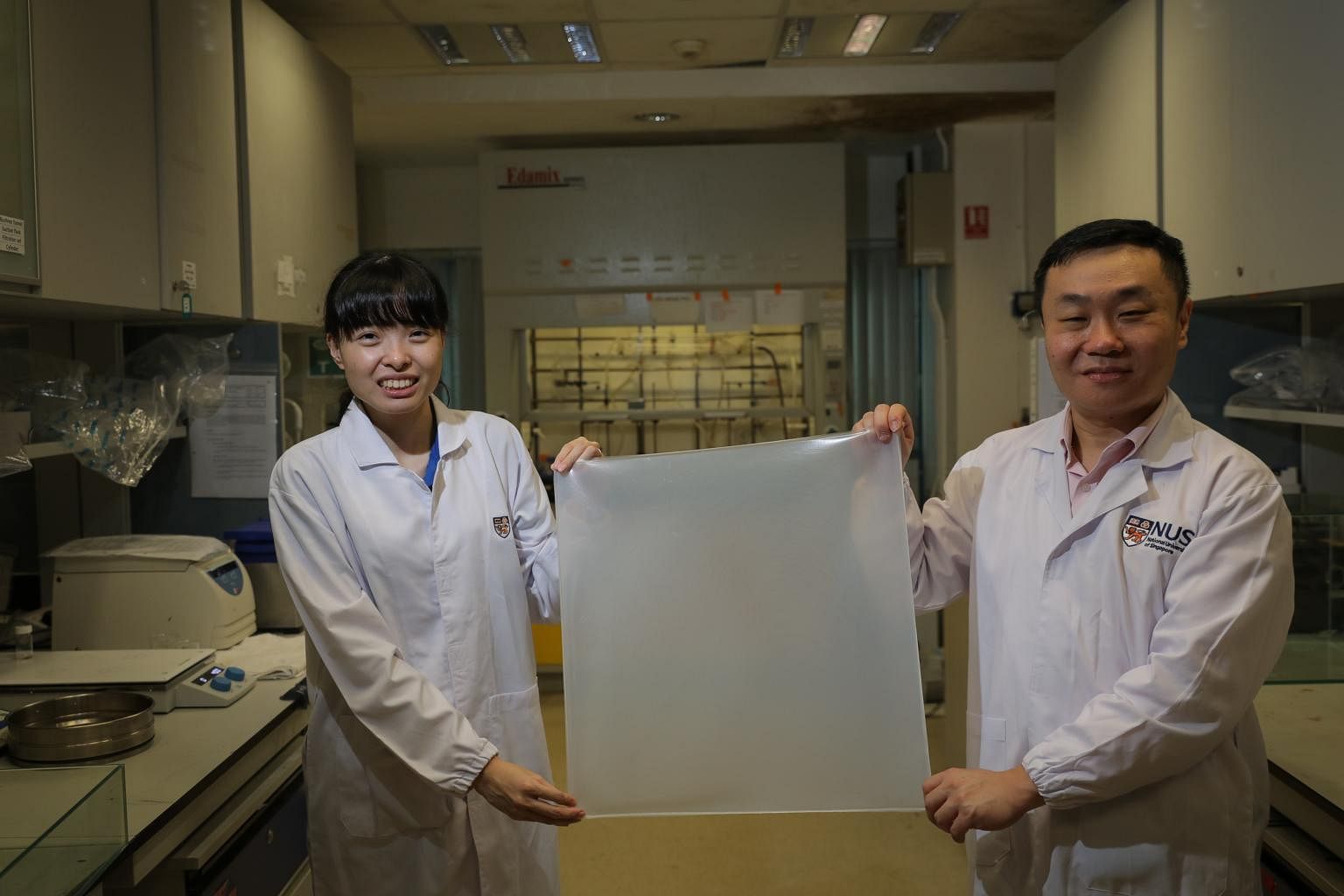

Prof Tan Swee Ching (right) and doctoral student Ms Yang Jiachen with the moisture-trapping material.

ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

When produced at scale, the light-weight, low-cost material has the potential to make uncomfortably hot clothing items from face masks to soldier uniforms more cooling, said Prof Tan.

HTX scientists hope to further optimise the material for equipment and clothing worn by firefighters, emergency medical services and other front-line officers who work under hot and humid conditions for long hours.

Currently, the material still needs to be improved for open environments, because its ability to capture sweat is hindered when exposed to ambient moisture.

Dr Saravana Kumar, HTX deputy director of the Human Factors and Simulation Centre of Expertise, said: "We are keen to explore the possibility of enhancing the efficacy of the material for non-encapsulated suits like firefighter suits, such that it can also deliver a significant cooling effect despite absorption of ambient moisture."

Meanwhile, the NUS team is looking for partners to commercialise the film.

Said Prof Tan: "The material for one suit costs $4 to produce in a lab environment, but this can be lowered when scaled up."

A personal protection suit costs around $10 online.