Science Journals: A long journey to restore carbon-rich peatlands in Indonesia’s Riau province

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Mr Wahyudi, a conservation and certification officer at Arara Abadi, planting a meranti sapling at the peat dome restoration site on Aug 14.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Trudging through vegetation three hours away from Riau’s capital, loose, dark earth and dry twigs crunched under my shoes.

Clumps of elephant dung were scattered across the area, a sign that a herd of endangered Sumatran elephants had paid a visit not long before us.

Five-year-old meranti and gelam trees – peat trees neatly arranged in rows – towered over us, and a line of saplings stood next to dug-up soil, waiting to be planted.

Holding the dry, crumbly soil in my hand, it was hard to believe that this was peat, which should be damp and spongy. But it was also difficult to picture the site as a former pulpwood plantation.

We were at a recovering peat dome under restoration in the middle of Asia Pulp and Paper (APP) Group’s plantation in Nilo district, a three-hour drive from Pekanbaru, the capital of the Indonesian province of Riau, on Aug 14. The plantation is run by the company’s subsidiary, PT Arara Abadi.

Part of the peat dome under restoration in Nilo district in Riau, Indonesia.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

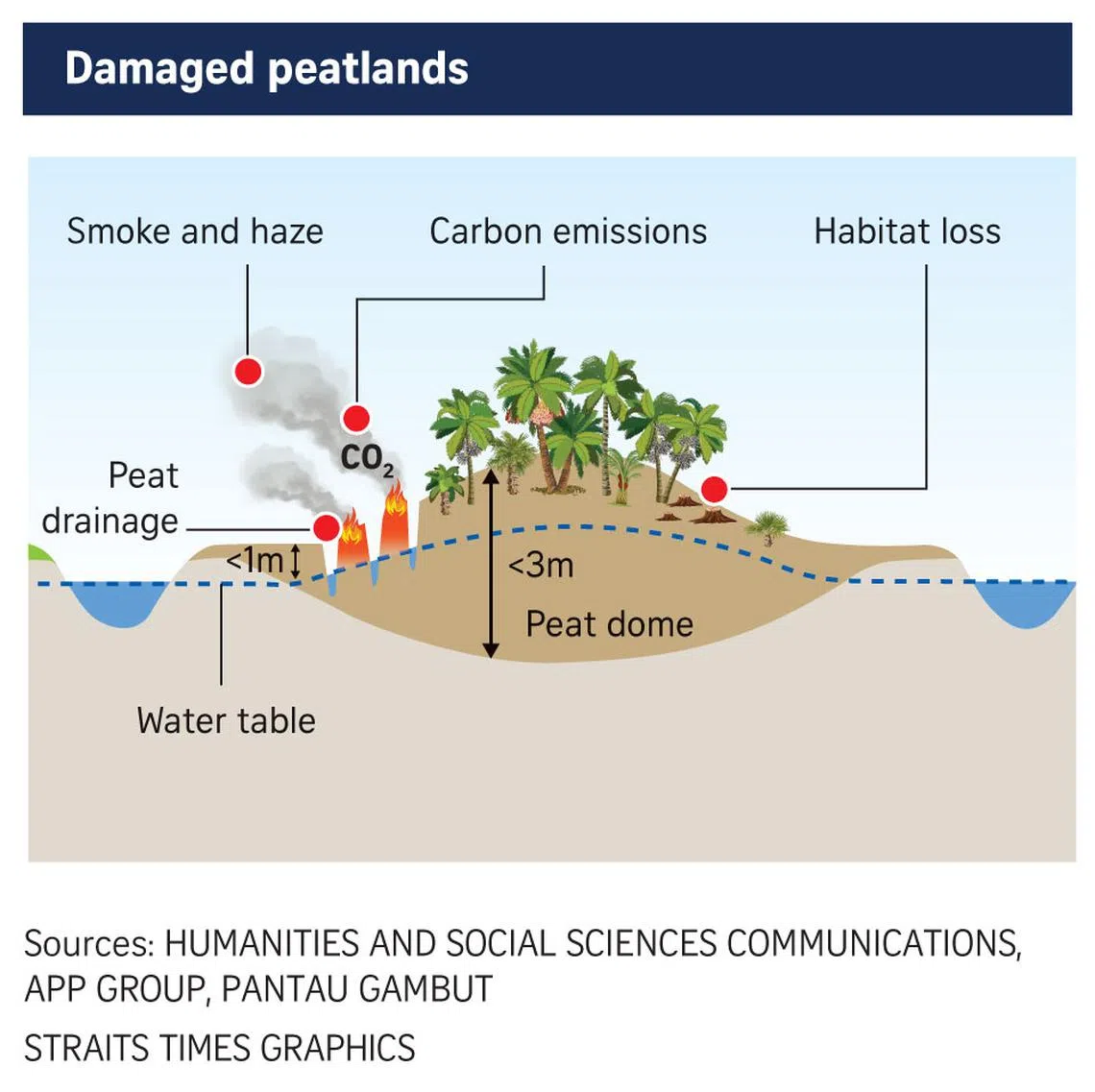

A peat dome lies on an elevated area above its surrounding peatland. Domes are of conservation value because they store more carbon and water, while supporting biodiversity, according to World Resources Institute Indonesia.

“We want to bring back the area’s previous ecosystem, but that would take about 100 years from now. So what we want now is for the ecological functions to come back first,” said Ms Jasmine Doloksaribu, head of landscape conservation and environment at APP’s forestry arm.

Unlike ordinary forest soil, peat is an accumulation of partially decayed plants, roots and branches over thousands of years. This makes peatlands rich in carbon, and Indonesia is home to the largest tropical peatlands in the world, mostly across Sumatra, Kalimantan and Papua.

Although peatlands cover just 3 per cent of the earth’s land surface, they store twice as much carbon as all the world’s forests combined. But peatlands have for decades been viewed in Indonesia as wasteland, eyed by agriculture giants and farmers for conversion into oil palm and pulpwood plantations, and farmland.

An area that was part of the peatlands APP was looking to conserve, but instead it was converted into an oil palm plantation by another party.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

When turning peatland into agricultural land, drains are carved into the land to bleed out the water that gives peat life. The parched peat turns into a vast tinderbox, setting off fast-spreading wildfires when land is torched for agriculture and production, or even when a cigarette butt falls or lightning strikes the land during dry seasons.

Peatland fires caused the 2015 haze that shrouded Singapore and South-east Asia, and APP was among several corporate culprits behind the haze crisis.

The firm, which has a presence in Singapore, was investigated by the National Environment Agency under the Transboundary Haze Pollution Act. Its paper products were temporarily banned by some supermarket chains.

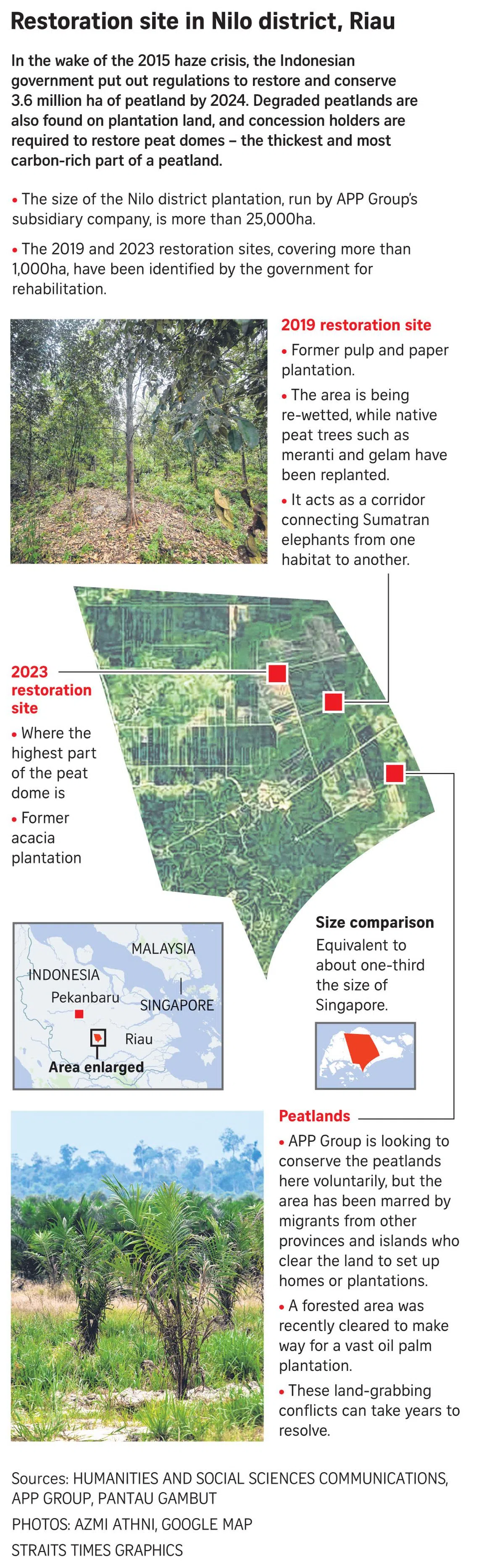

In the wake of the 2015 haze crisis, the Indonesian government put out regulations to restore and conserve 3.6 million ha of peatland by 2024. Degraded peatlands found on plantation land must be restored by the concession holders, especially peat domes – the thickest and most carbon-rich part of a peatland.

An aerial view of the plantations at APP Group’s pulpwood supplier Arara Abadi in Perawang, Riau, on Aug 13.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

Of its 2.6 million ha of concession land, APP said it has promised to set aside about 650,000ha, or 25 per cent of it, for conservation and restoration. The area includes both peatland and mineral soil land.

Some of the 650,000ha comprises peat domes identified by the Indonesian government for restoration and protection, and one of them is the more than 1,000ha peat area in Nilo district – the size of some 1,400 football fields.

Reviving degraded peat

APP took The Straits Times to the southern portion of the peat dome, where restoration works began in 2019 on the former acacia plantation. In 2023, restoration began on the northern portion – the highest peak of the peat dome.

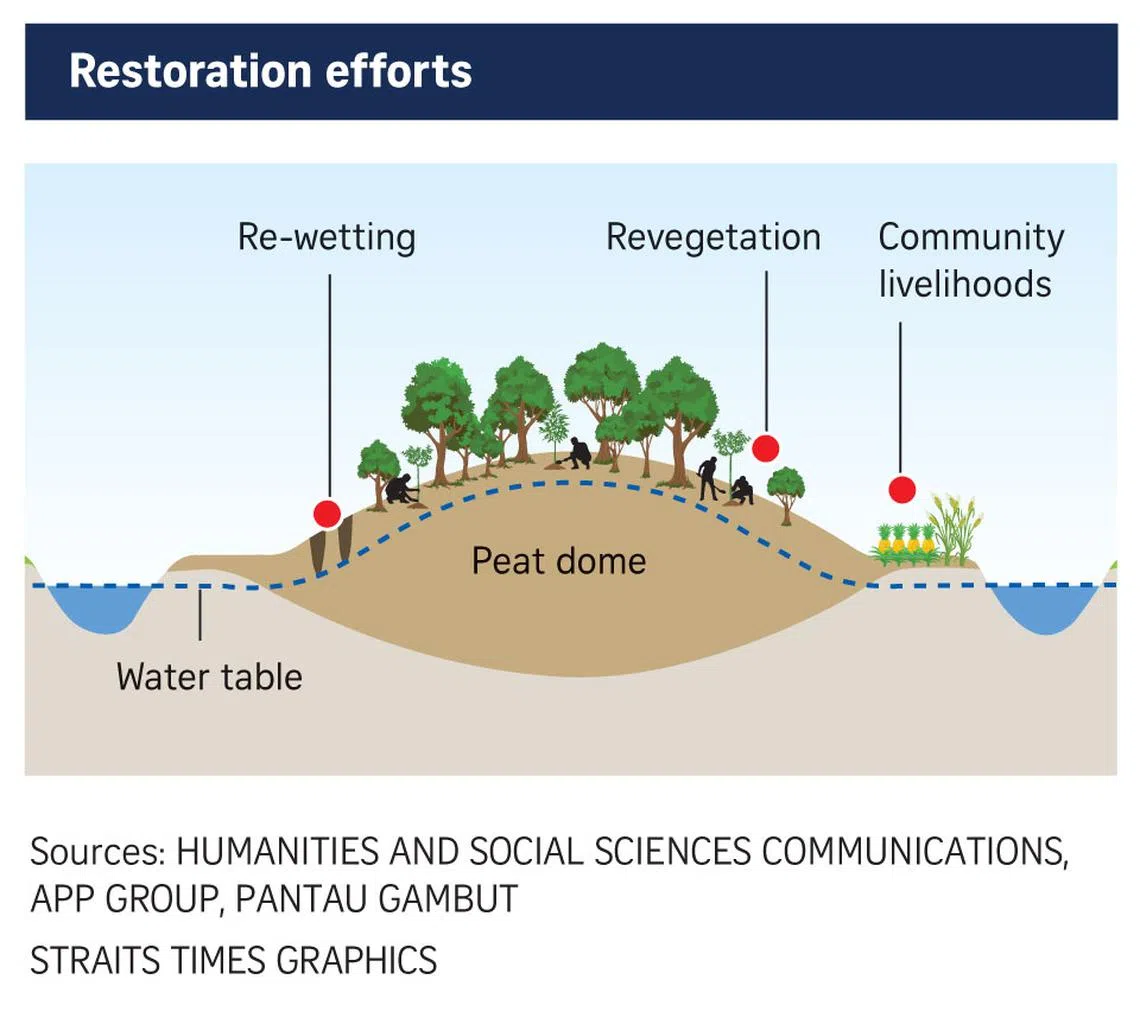

In restoring a peat dome, the most critical thing is to return water to the parched soil. The canals must be blocked so that rainwater can seep back into the peat, eventually raising the water table of the peatland. Six canal blocks have been constructed to rehydrate the southern 2019 site.

According to the Indonesian authorities, the water levels of peatland under restoration should be no lower than 40cm below the surface. Ms Doloksaribu said the water table of the site tends to be 20cm to 40cm below the surface.

One of the canal blocks (foreground) in Nilo district.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

Yet, the surface of the dome was very dry, even accounting for August being the dry season.

Mr Benjamin Tay, strategic adviser at Singapore-based environmental charity PM.Haze, said: “A dry landscape is quite common for degraded peatlands. Water will flow away from the dome through canals that may be constructed to facilitate agriculture.”

Revegetation is the next step after re-wetting the peat, and most of the southern area was planted with native peat swamp trees such as meranti, gelam and tenggek burung. The five-year-old trees have yet to form a dense canopy.

Ms Jasmine Doloksaribu interacting with a Sumatran elephant named Melina who is under the care of APP Group at an arboretum in Perawang, Riau, on Aug 13.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

For every hectare of land, 500 trees are planted, and their survival rate is 80 per cent.

Ms Doloksaribu said: “Wild elephants love to snack on the leaves and shrubs.” She noted that herds of 40 to 70 of the mammals have used the peat dome area as a corridor, connecting them from one habitat to another.

Can peat trees be used for pulp and paper?

To marry paper production and peat conservation, scientists and non-governmental organisations have called for companies to look into alternative pulpwood trees that can grow in waterlogged peat, to reduce the reliance on industrial acacia and eucalyptus trees, which grow only on drained peatlands.

In 2016, APP’s research and development (R&D) centre in Perawang, Riau, started exploring such alternative species for pulp production. Out of 30 native species studied, four were shortlisted – gelam, balangeran, bush merah and geronggang. The balangeran was later deemed unsuitable for pulp-paper material because it is sticky.

The native plant nursery at the R&D centre of APP Group’s pulpwood supplier Arara Abadi in Perawang, Riau, on Aug 13.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

While the remaining three species are still under study, they grow more slowly than the commercial acacia and eucalyptus, making them unsuitable at the moment for producing paper.

APP then decided to prioritise those native species, including terentang, for reforestation on conserved APP land. Occasionally, local plants used for replanting come from the R&D centre’s native species nursery.

Research is still ongoing into using peat-suitable trees for pulp and paper production. Dr Abdul Gafur, R&D head for Riau at the centre, said its current focus is on improving the growth and properties of the crop trees. While the native alternatives also merit study, that will come later.

Mr Tay said: “Looking at it from an ecosystem perspective, what’s important is the fact that plantation owners like APP and others have embarked on projects to restore peatlands within their concession areas.

“The rate of transition, of course, can be contested. We can definitely say they should move faster. But at the end of the day, these are private companies with very strong commercial interests... Of course, they need to answer for whatever environmental degradation they’ve caused.”

Land rife with conflict

Ms Doloksaribu added that Nilo district is a complex area where land conflict is rife. The eastern edge of the district comprises peatlands that APP has been looking to conserve, but parts of them have been encroached on by migrants from other provinces or Indonesian islands since about 2016. These migrants illegally set up houses and grow oil palm, among other farming activities.

We drove past a vast area that had recently been converted into a plantation; young oil palm trees sprouting out of dried, carved peatland. When these illegal tree farms are discovered, they are reported to the police, but law enforcement takes awhile, said Ms Doloksaribu.

In 2017, heavy machinery used for logging was seized from a separate area in Nilo district that had been marked for conservation. The perpetrator was in 2023 sentenced to four years in prison.

Conflicts with the squatters can flare up if the illegal oil palm plantations obstruct APP’s operations, said Ms Doloksaribu.

The reality also is that concession lands must continue to be scrutinised by various environmental watchdogs.

Mr Agiel Prakoso from Jakarta-based Pantau Gambut – which tracks peatland health – noted that during the dry season in 2020 and 2023, peatlands under restoration at oil palm and acacia plantations had water table levels below 40cm, suggesting they were not being watered well.

A 2021 field study of 43 concession areas in seven provinces by Pantau Gambut found that 91 per cent of concession areas marked for peat restoration had no restoration infrastructure.

At PT Arara Abadi’s concessions in the Siak and Bengkalis region, Pantau Gambut found burnt areas replanted with acacia. According to government regulations, plantations are prohibited on burnt peatlands.

A 2023 Greenpeace Indonesia report alleged that between 2013 and 2022, up to 75,000ha of land was deforested by APP’s supplier concessions or companies connected to the paper giant. These allegations came 10 years after APP pledged to halt deforestation and peatland conversion in 2013.

- Marshy peatlands, long viewed as undesirable landscapes, have for decades been drained of water and deforested, and converted into palm oil, and pulp and paper plantations.

- The parched peat turns into a vast tinderbox, setting off fast-spreading wildfires when the land is torched for agriculture. Peatland fires caused the 2015 haze that shrouded Singapore and South-east Asia.

- The flames and smoke unleash peat’s locked-in carbon, contributing to the bulk of Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Re-wetting

Man-made canals are dammed up to prevent water from draining out further. When rain falls, water can seep into the peat, raising the water table of the peatland. Wet peat is also less likely to catch fire.

Re-vegetation

Native peat swamp species are replanted on a degraded site to reforest the area. At times, an area can regenerate on its own without much human intervention.

Community livelihoods

Villagers can be allowed to grow crops that are suitable for waterlogged soil, such as water chestnut, water spinach and swamp jelutung, which can produce timber and latex.