S’pore consumers unlikely to see big hike in electricity prices from clean imports: Observers

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The imported electricity – produced from sources such as solar, wind and hydropower – is expected to be priced at a premium.

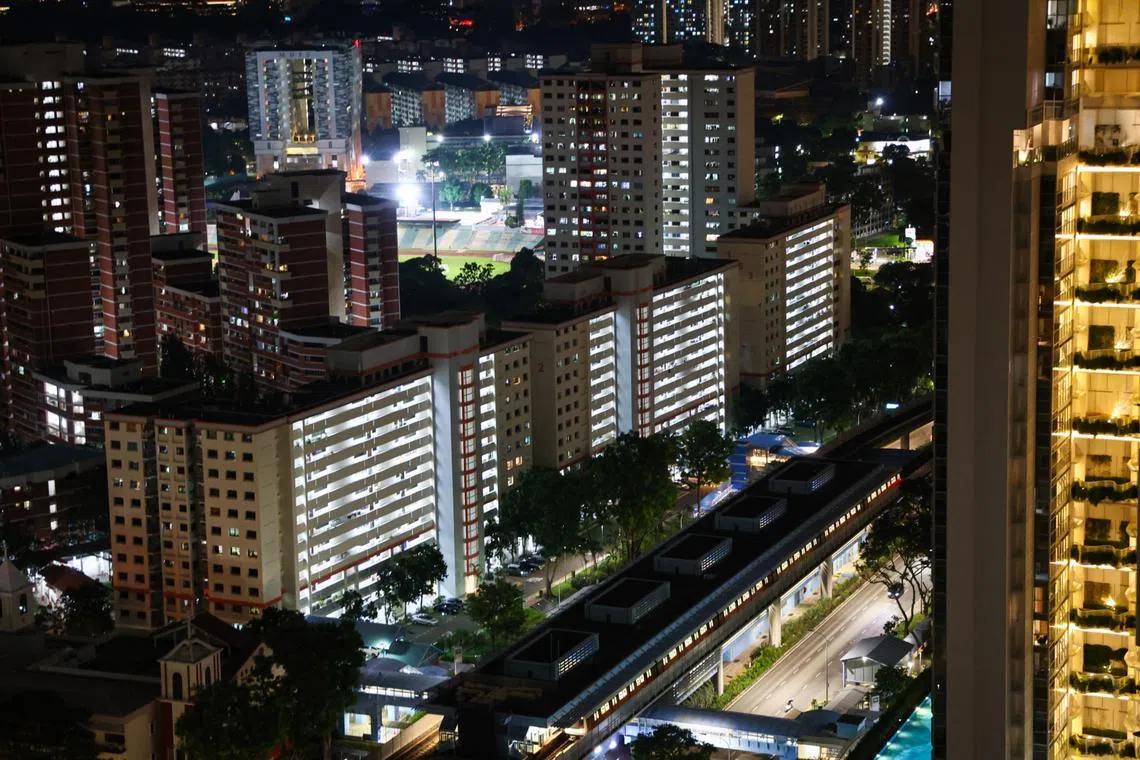

PHOTO: LIANHE ZAOBAO

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – The average consumer will likely not face a marked increase in his electricity bills when Singapore begins its renewable energy imports over the next few years, said observers. They added that the clean power will mostly be purchased by companies looking to slash their emissions.

The imported electricity – produced from sources such as solar, wind and hydropower – is expected to be priced at a premium, as a result of the hefty price tag that comes with the necessary battery storage solutions and electricity transmission cables.

In September, Singapore raised its electricity import target

Seven companies will be importing around 3.4GW of solar energy from Indonesia, five of which are expected to start commercial operations for their projects from 2028.

In response to queries from The Straits Times, a spokesman for the Energy Market Authority (EMA) said the cost of low-carbon electricity imports may not be more expensive than other sources of low-carbon electricity.

Renewable imports aside, Singapore is considering a host of other clean energy options

“In evaluating the various electricity import proposals, EMA considers a range of factors, including price-competitiveness and source diversity. (The agency) is actively collaborating with importers to optimise their projects and reduce costs, such as by optimising landing sites and sea corridors,” said the spokesman.

A spokesman for Vena Energy, which received conditional approval earlier in September to import 400MW of solar power from Indonesia’s Riau province, told ST that the firm is committed to keeping the cost of its electricity at a “competitive price”.

The eventual price will depend on several factors, such as the development of transmission infrastructure, regulatory approvals and prevailing market conditions at the time of the project’s construction.

The renewable energy company has partnered Shell Eastern Trading for the development of the import project, with the oil giant committing to purchase clean electricity from it.

Shell has a target of getting to net-zero emissions by 2050, which means it has to reduce emissions from its operations and from fuels and energy products it sells to its customers.

A spokesman for Pacific Medco Solar Energy, which will be importing 600MW of electricity from Indonesia’s Bulan island, said it will be conducting tenders for all its onshore and offshore assets to ensure that the electricity delivered to Singapore is cost-competitive. It also expects its buyers to be large corporate energy users.

Mr Melvin Chen, Wood Mackenzie’s head of power and renewables consulting for the Asia-Pacific, said he expects the electricity imports to be purchased by companies with sustainability targets, and therefore the average Singaporean would likely not bear the brunt of higher prices.

In particular, big tech companies with data centres may have more urgency to source clean energy to reduce their emissions, he said. For example, companies such as Meta and Google, which have operations in Singapore, have targets of getting to net-zero emissions by 2030.

Renewables now make up only about 5 per cent of electricity generated from the grid, which makes decarbonisation a challenge.

Dr Victor Nian, founding co-chairman of the Centre for Strategic Energy and Resources, an independent think-tank based in Singapore, said having more renewable energy imports will allow companies here to secure more low-carbon electricity, albeit at a potentially higher price.

However, he said that part of the cost will likely be passed on to the regular consumer, as all imported low-carbon electricity will be sent to the grid by default.

As the share of renewable energy imports increases, Mr Chen said, Singapore will inevitably require more backup gas-fired generation capacity for energy security reasons.

And while electricity importers will likely have to bear the costs of such infrastructure, some costs will inevitably be passed through to end consumers, he added.

Clean electricity import projects will be priced at a premium, even as the price of renewables has fallen over the years, Mr Chen said.

A solar import project from Indonesia, for instance, could cost upwards of $300 per megawatt hour (MWh) of electricity, he added.

For comparison, the cost of electricity from natural gas in Singapore is around $214 per MWh, while a solar project in Indonesia could cost about US$60 (S$78) per MWh locally.

But these costs could vary widely, depending on the distance of the project from Singapore, and the type of renewable energy produced.

Given the intermittent nature of renewables, battery storage solutions, which are still costly, will be required to store excess solar power for use during night-time when the sun does not shine, or when there is no wind.

High-voltage subsea cables – which transmit the electricity – will also add to the project’s cost substantially, amid a looming shortage of these cables as factories struggle to ramp up production.

In addition, all electricity import projects must have a load factor – or power efficiency – of at least 75 per cent in order to meet the power generation requirements of the import agreements, said Mr Chen.

This means that the average amount of electricity produced by a solar or wind farm must be at around 75 per cent of the plant’s total generation capacity.

However, the EMA’s newly launched Future Energy Fund could help reduce the costs of these import projects, Mr Chen said, though the structure of the fund has not yet been announced.

The fund, which can be used to offset the cost of infrastructure like high-voltage subsea cables, will be set up later in 2024 and will receive an initial tranche of $5 billion from the Government.