Institute of Policy Studies report wants Singapore families, society to discuss and better plan end-of-life matters

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Although Singapore tops the world in life expectancy, with the average Singaporean enjoying the longest span of living in good health, there has also been a rise in the number of unhealthy years people here live.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE - When it comes to talking about death and dying, Singaporeans uncharacteristically leave things to the last minute.

But this has to change as the country ages, with a robust national plan needed to prepare people for their final days, recommended the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) in a comprehensive new report on Friday (July 12).

"As Singaporeans, we plan for almost everything, from the first house that we purchase to the child's first school," said IPS research associate Yvonne Arivalagan, one of the study's authors. "But this is a really important aspect of life that very few people actually plan for."

The 97-page report highlighted aspects of end-of-life care where gaps remain and recommended improvements, including in the areas of costs, family support, and the ease of planning out and communicating one's final wishes. It is based on the findings of a group of experts from various fields, who studied the issue over a two-year period.

"We find that one of the most common scenarios is that people just don't talk about this until it's too late," Ms Arivalagan added. "At that moment, it's very distressing and there are a lot of financial considerations to think about... The idea is to talk about this issue much earlier."

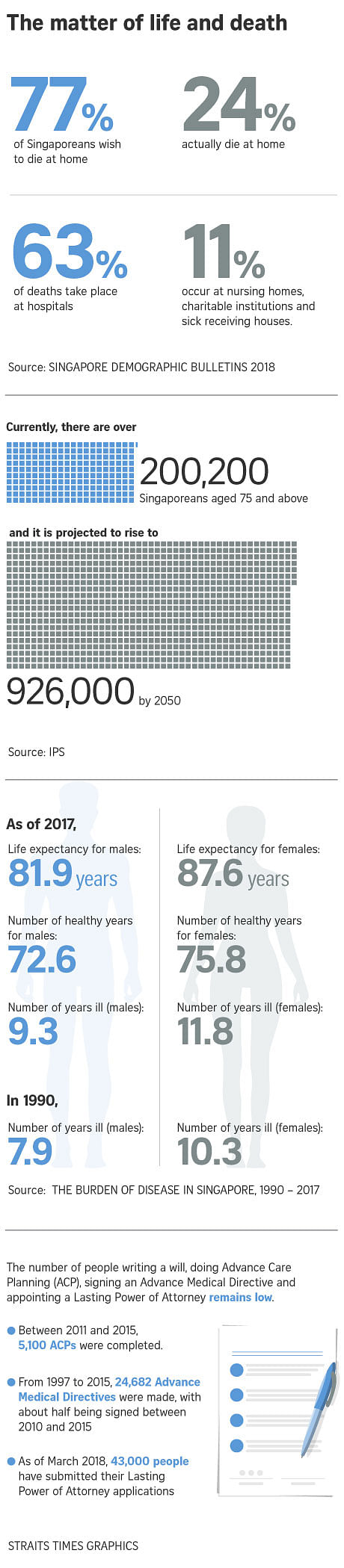

A Lien Foundation survey in 2014 found that 77 per cent of people preferred to die at home. But data from last year's Singapore Demographic Bulletin showed that only 24 per cent achieved this, with 69 per cent dying in hospitals or nursing homes.

And although Singapore tops the world in life expectancy, with the average Singaporean enjoying the longest span of living in good health, there has also been a rise in the number of unhealthy years people here live.

When it came to costs, the report's authors noted that people may find it cheaper to die in a hospital than at home, simply because of how government subsidies are structured.

Financing programmes for end-of-life care services are also less developed than in the rest of the healthcare system, since most care is informal and provided by families or the community.

In fact, healthcare costs can be the source of familial rifts, especially when patients decline treatment so that their loved ones will not have to shoulder the burden of their medical bills.

IPS senior research fellow Christopher Gee, who co-authored the study, noted that Singapore has traditionally invested heavily in acute hospitals, and less in long-term care. Although this is changing , subsidies are still skewed towards the old model, he said.

"It's not easy to level this up. But going forward, we will need to think about how we can incentivise people to seek care at home or in the community, rather than in the hospital, because that's a big reason why so many of us end up dying there."

At the same time, the authors noted that families often have a "culture of silence" when it comes to end-of-life issues, making it difficult for the tough conversations about a person's care preferences to take place.

For instance, a critically-ill person may not want to inform family members of a poor diagnosis in order to avoid upsetting them, or vice versa. Others may have a superstitious aversion to talking about death, or be reluctant to dampen a loved one's will to live.

These cultural and emotional barriers must be tackled in any programme dealing with end-of-life issues, the study's authors said.

They also pointed out that there needs to be more awareness of advance care plans and the Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) scheme, which help a person's family make decisions according to their wishes if they are no longer able to do so.

While advance care plans serve as guides to a person's treatment preferences, LPAs are legally-binding documents through which they can appoint someone to make decisions for them should they lose their mental capacity.

Documentation processes for these and other related services could be merged under a single administrative body, simplifying matters for families, the authors suggested.

On a national level, schools, workplaces and even religious organisations can encourage people to start conversations on these issues and normalise them as part of life, they added.