Remembering Lee Kuan Yew

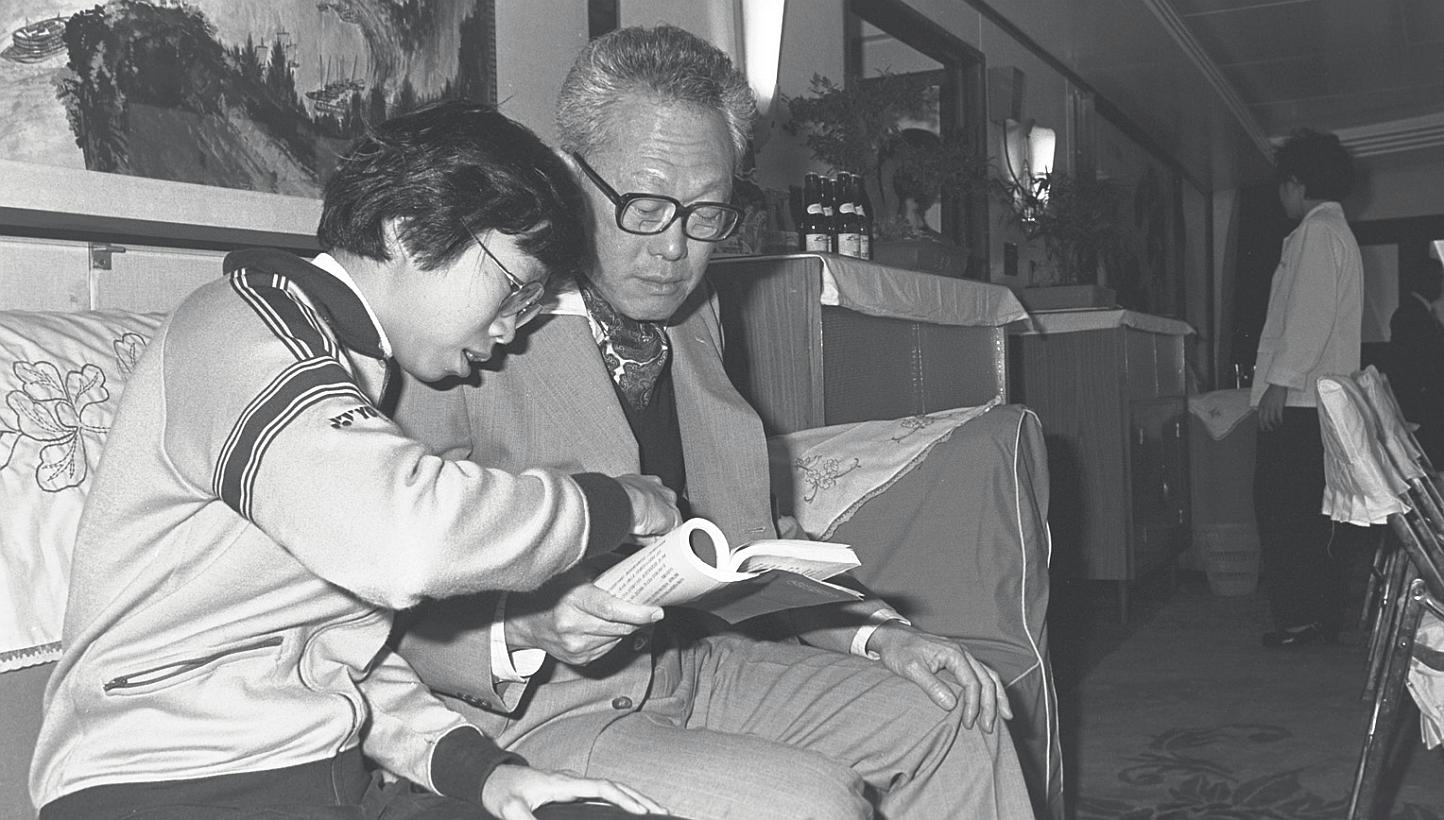

Remembering Lee Kuan Yew: Daughter Lee Wei Ling on Mr Lee as a father

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

SINGAPORE - Dr Lee Wei Ling, 60, the only daughter of the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew, pays tribute to her father in a piece published in The Straits Times on March 24, 2015.

In it, she notes how he wasn't one to panic because "doing so would never positively affect the outcome of any situation".

Mr Lee died at the age of 91 on March 23.

In previous essays for The Sunday Times, Dr Lee, who is the director of the National Neuroscience Institute, also offered glimpses into the private life of her parents. We reproduce some of her pieces here.

Published March 24, 2015

My father was a workaholic

My parents and I were in hospital waiting for my father to have a stent put in, but none of us said a word.

It was not because of an unspoken tension over the state of his health - we were all too busy working.

There my father sat on his hospital bed huddled over his laptop with my mother, who was checking his draft, while I, too, had a computer on my lap.

As I watched the three of us in the room, it occurred to me that any passer-by would get no sense at all that my father would soon be going in for an angioplasty.

Yes, my father was a workaholic, and as a 73-year-old holding the post of senior minister in 1996, he did not see his impending surgery as reason enough to stop working.

But the episode also showed me how my father stoically approached the challenges before him without a hint of emotion or anxiety. He was unflappable.

He found it was never helpful to panic, because doing so would never positively affect the outcome of any situation.

I believe these were the steely qualities that took him through his 31 tumultuous years as prime minister, but they may not always work as well at home.

In my family, I am most like my father in temperament, and when you have two strong-willed people in one house, it can get difficult to control.

Occasionally, we would get into fights when neither of us would back down.

In 2002, one such disagreement resulted in my moving out of our Oxley Road home.

My father wanted me, an exercise fiend, to stop working out because my bones had become so fragile that I suffered repeated fractures.

He called me into his study and gave me an ultimatum.

"The doctors told me you could cripple yourself with the exercise. As long as you are staying in this house, I've to look after your welfare," he said.

Not wanting to give up my exercise, I decided to move out to live with my brother Loong.

It was probably not the response my father had anticipated, but he realised then that I was a 47-year-old adult who was going to make up my own mind on things.

The next year, when I told my father I was going to hike a volcanic crater in Hawaii immediately after I was discharged from hospital, he gave a very different response.

"Be careful."

He said nothing more.

Published Aug 5, 2012

At Oxley Road, we value the frugal life

I grew up in a middle-class family. Though they were well-off, my parents trained my brothers and me to be frugal from young.

We had to turn off water taps completely. If my parents found a dripping tap, we would get a ticking off. And when we left a room, we had to switch off lights and air-conditioners.

My father's frugality extends beyond lights and air-conditioners. When he travelled abroad, he would wash his own underwear, or my mother did so when she was alive. He would complain that the cost of laundry at five-star hotels was so high he could buy new underwear for the price of the laundry service.

One day in 2003, the elastic band on my father's old running shorts gave way. My mother had mended that pair of shorts many times before, so my father asked her to change the band.

But my mother had just had a stroke and her vision was impaired. So she told my father: "If you want me to prove my love for you, I will try."

I quickly intervened to say: "My secretary's mother can sew very well. I will ask her to do it."

My parents and I prefer things we are used to. For instance, the house we have lived in all my life is more than 100 years old.

When we first employed a contractor-cum-housekeeper, Mr Teow Seong Hwa, more than 10 years ago, he asked me: "Your father has worked so hard for so many years. Why doesn't he enjoy some luxuries?"

I explained we were perfectly comfortable with our old house and our old furniture. Luxury is not a priority.

Mr Teow has since become a family friend, so he now understands we are happy with our simple lifestyle.

For instance, my room has a window model air-conditioner. Most houses now have more sophisticated air-conditioning systems. So Mr Teow shopped for a window unit in Malaysia, so I would have a spare unit if my current one broke down.

All the bathrooms in our house have mosaic tiles. It is more practical than marble which can be slippery if wet. But it is now difficult to buy mosaic in Singapore. So again, Mr Teow bought mosaic tiles from Malaysia to keep in reserve in case some of our current tiles broke or were chipped.

I have three Casio watches, but use only one. Recently, when I woke up in the middle of the night and could not find the Casio I usually wore, I looked around for the other two. I found them in a drawer, together with two Tag Heuer watches that my brother Hsien Yang had given me recently, as well as a Seiko that my father had given me decades ago but which is still working fine.

My instinct had first led me to look frantically around for the original Casio. After 30 minutes, I knew that I was not going to find it that night. So I strapped on another of my Casios, comforting myself that I would not have got round to wearing my other watches if I had not misplaced my usual one.

I am frugal about my clothing too. I had only two batik wrap-around skirts that I bought in Indonesia more than 20 years ago. My girlfriends and my sister-in-law Ho Ching noticed that I wore the same two skirts almost all the time, and probably thought I looked scruffy. So they bought me more than 20 new skirts.

I have begun using three of the 20, and plan to wear them out before using the rest. And I have not discarded my two original wrap-arounds.

I have stuffed one into my backpack so I can whip it out as and when the occasion demands and I have to appear somewhat more respectable than in my usual shorts and T-shirt.

Frugality is a virtue that my parents inculcated in me. In addition to their influence, I try to lead a simple life partly because I have adopted some Buddhist practices and partly because I want to be able to live simply if for some reason I lose all that I have one day.

It is easy to become accustomed to a luxurious lifestyle. Some people believe that they will not miss their luxuries if for some reason they were to lose them, I think they are mistaken. I think they will miss them and be unable to reconcile themselves to a simpler lifestyle.

So I have trained myself to be satisfied with necessities and forgo luxuries.

Published Oct 23, 2011

Living a life with no regrets

When all is said and done, my father has led a rich, meaningful and purposeful life

About 20 years ago, when I was still of marriageable age, my father Lee Kuan Yew had a serious conversation with me one day. He told me that he and my mother would benefit if I remained single and took care of them in their old age. But I would be lonely if I remained unmarried.

I replied: "Better lonely than be trapped in a loveless marriage."

I have never regretted my decision.

Twenty years later, I am still single. I still live with my father in my family home. But my priorities in life have changed somewhat.

Instead of frequent trips overseas by myself, to attend medical conferences or to go on hikes, I only travel with my father nowadays.

Like my mother did when she was alive, I accompany him so that I can keep an eye on him and also keep him company. After my mother became too ill to travel, he missed having a family member with whom he could speak frankly after a long tiring day of meetings.

At the age of 88, and recently widowed, he is less vigorous now than he was before May 2008 when my mother suffered a stroke. Since then I have watched him getting more frail as he watched my mother suffer. After my mother passed away, his health deteriorated further before recovering about three months ago.

He is aware that he can no longer function at the pace he could just four years ago. But he still insists on travelling to all corners of the Earth if he thinks his trips might benefit Singapore.

We are at present on a 16-day trip around the world. The first stop was Istanbul for the JPMorgan International Advisory Council meeting. We then spent two days in the countryside near Paris to relax. Then it was on to Washington DC, where, in addition to meetings at the White House, he received the Ford's Theatre Lincoln Medal.

As I am writing this on Thursday, we are in New York City where he has a dinner and a dialogue session with the Capital Group tonight, and Government of Singapore Investment Corporation meetings tomorrow. After that, we will spend the weekend at former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger's country home in Connecticut. Influential Americans will be driving or flying in to meet my father over dinner on Saturday and lunch on Sunday.

Even for a healthy and fit man of 88, the above would be a formidable programme. For a recently widowed man who is still adjusting to the loss of his wife, and whose level of energy has been lowered, it is even more challenging.

But my father believes that we must carry on with life despite whatever personal setbacks we might suffer. If he can do something that might benefit Singapore, he will do so no matter what his age or the state of his health. For my part, I keep him company when he is not preoccupied with work, and I make sure he has enough rest.

Though I encourage him to exercise, I also dissuade him from over exerting himself. I remind him how he felt in May last year when, after returning from Tokyo, he delivered the eulogy at Dr Goh Keng Swee's funeral the next day.

He had exercised too much in the two days preceding the funeral, against my advice. So naturally, he felt tired, and certainly looked tired on stage, as he delivered his tribute to an old and treasured comrade-in-arms. A few of my friends were worried by how he looked and messaged me to ask if my father was OK. Now when I advise him not to push himself too hard, he listens.

The irony is I did not take my own advice at one time and it was he who stopped me from over-exercising. Once, in 2001, while I was recovering from a fracture of my femur, he limited my swimming. He went as far as to ask a security officer to time how long I swam. If I exceeded the time my physician had prescribed, even if it was just by a minute, he would give me a ticking off that evening.

Now the situation is reversed. But rather than finding it humorous, I feel sad about it.

Whether or not I am in the pink of health is of no consequence. I have no dependants, and Singapore will not suffer if I am gone. Perhaps my patients may miss me, but my fellow doctors at the National Neuroscience Institute can take over their care. But no one can fill my father's role for Singapore.

We have an extremely competent Cabinet headed by an exceptionally intelligent and able prime minister who also happens to be my brother. But the life experience that my father has accumulated enables him to analyse and offer solutions to Singapore's problems that no one else can.

But I am getting maudlin. Both my father and I have had our fair share of luck, and fate has not been unfair to us. My father found a lifelong partner who was his best friend and his wife. Together with a small group of like-minded comrades, he created a Singapore that by any standards would be considered a miracle. He has led a rich, meaningful and purposeful life.

Growing old and dying occurs to all mortals, even those who once seemed like titanium. When all is said and done, my father - and I too, despite my bouts of ill health - have lived lives that we can look back on with no regrets. As he faces whatever remains of his life, my father's attitude can be summed up by these lines in Robert Frost's poem Stopping By Woods On A Snowy Evening:

The woods are lovely, dark, and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

Published Oct 2, 2011

Love does indeed spring eternal

Emotional ties don't come to an end with the passing away of a loved one

My friend Balaji Sadasivan passed away on Sept 27 last year. In the obituaries section of The Straits Times last Tuesday, exactly one year after his death, there was a sonnet by Balaji himself: "But even in gloom, one truth is fundamental, from time immemorial, love springs eternal."

A week after Balaji died, on Oct 2, my mother passed away peacefully at home. "Love springs eternal" - but what comfort is that to the one who has departed and can no longer reciprocate our love?

This thought slipped randomly in and out of my mind as I was exercising last week. Then my Blackberry buzzed. I read the incoming e-mail. It was from my father - brief, concise, a mere statement of fact, yet what was unsaid but obvious was his love and concern for us, his children.

I suddenly realised that love does spring eternal. Papa, my brothers Hsien Loong and Hsien Yang, and my sisters-in-law Ho Ching and Suet Fern, and I are still bound by our love for Mama and will continue to be for many more years.

For the first few weeks after her devastating stroke on May 12, 2008, my family and the doctors met often to discuss how best to minimise her suffering and perhaps enable her to recover to some extent.

The physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech therapists all did their best, but Mama did not improve. The May 12 stroke was more extensive, and involved more brain regions controlling movement than her first stroke on Oct 25, 2003.

But Papa remembered how well she had recovered from that first stroke, which had occurred while my parents were visiting London. By the end of that year, we were celebrating Mama's 83rd birthday on Dec 21 in a private room at Goodwood Hotel in Singapore.

Now, in October 2008, Papa knew that if Mama survived she would never be able to walk independently. But he felt that so long as she knew she was an important part of his life, she would still find life worth living.

He told her: "We have been together for most of our lives. You cannot leave me alone now. I will make your life worth living in spite of your physical handicap."

She replied: "That is a big promise."

Papa said: "Have I ever let you down?"

Mama tried her best to cooperate with the therapists. But it seemed a useless struggle. Even swallowing a teaspoon of semi-solid food was a huge effort. Then more bleeds occurred and her condition deteriorated. We, her family, decided that no further active treatment should be sought. We arranged to bring her home and nurse her there.

Before we brought her home for the final time, Papa arranged for her to stop at the Istana, to see her favourite spots in the grounds. We wheeled her to where she had planted sweet-smelling flowers such as the Sukudangan and the Chempaka. Then we wheeled her to the swimming pool, where she had swum daily.

We showed her the colourful little "windmills" she had arranged around the pool. She also saw the colourful wetsuits that Papa had arranged to be made for her to keep her warm in the water.

He and I had been convinced that she had to exercise to remain fit. So come rain or shine, she would don a wetsuit and swim. Even when travelling, she would swim in the hotel pool.

On one trip, Mama said to Papa: "Today is a public holiday in Singapore. Can I take a break from swimming."

Papa replied: "No, have a swim. You will feel better after that."

As a neurologist, I knew that after the first bleed in 2003, a second was likely. But I did not want to burden Papa or Mama with this knowledge.

Still, unknown to me, Papa had sensed that she could easily rebleed. He told us later that they had both discussed death. They had concluded that the one who died first would be the lucky one. The one remaining would suffer loneliness and grief.

Mama deteriorated further after she returned home. Finally, she reached a stage when she could not even speak and seemed unaware of her surroundings. But she was always aware of Papa's presence.

When Papa travelled, she would stay awake at night waiting for his phone call. When I began travelling with him, he usually would tell her on the phone: "Bye dear, I am passing the phone to Ling." Those were the times when I could hear her actively trying to vocalise.

When Mama passed away, I was at her bedside, watching her fade as her respiration became more shallow and feeble until it finally stopped. I did not try cardiopulmonary resuscitation. It would have been futile to have done so and cruel.

I called to ask my family physician to sign the death certificate, then returned to my room in a daze. Papa waited until the people from the Singapore Casket Company arrived. He showed them the jacket he wished Mama to wear and asked them to do their best to make her look attractive.

The wake lasted for three days. Hsien Loong and Hsien Yang, together with their wives, took turns to stand by the coffin and greet well-wishers.

I was tired and rested at home, only attending the wake on the first evening to greet my friends and colleagues. I hoped that by resting I would recover by the day of the funeral.

Most of the time, my mind was blank. I thought I had my emotions under control. It was only at the funeral, when it was my turn to deliver the eulogy, that the finality of Mama's passing hit me. I managed to control my tears but my voice was strained with emotion.

Three days after the cremation, the urn containing my mother's ashes was delivered to our home. We all stood and bowed as the urn was brought into the dining room.

A few days later, I noticed that Papa had moved from his usual place at the dining table so as to face a wall, on which were placed photographs of Mama and himself in their old age. He tried various arrangements of the photos for a week before he was satisfied.

He also moved back to the bedroom he had shared with Mama for decades before her final illness. At the foot of his bed were another three photographs of Mama and himself.

The health of men often deteriorates after they lose their wives. The security officers and I watched Papa getting more frail every day. His facial features were grim, perhaps to mask his sadness and grief. I took one day at a time and persuaded him not to undertake any arduous trips to America or Europe. China and Japan were near enough and manageable. I was pleased to get him out of the house.

By July this year, Papa's health had stabilised and even begun to improve gradually. I reminded myself of the analogy I used for him - titanium. Titanium is light but strong. It can bend a little, but it will not snap unless it is under overwhelming force.

Physically, we all eventually succumb. Papa is also mortal. But he is psychologically stronger than most people. Life has to carry on, and he will keep going so long as he can contribute to Singapore.

As I was halfway through writing this article, I went out of my room for a drink of water and saw a note from Papa addressed to all three of his children. It read:

"For reasons of sentiment, I would like part of my ashes to be mixed up with Mama's, and both her ashes and mine put side by side in the columbarium. We were joined in life and I would like our ashes to be joined after this life."

Published Aug 14, 2011

Remembering the childhood years

Our parents were firm but they never put pressure on their three children to perform well

My father became prime minister of Singapore in 1959. At that time, we had two "black-and-white" Chinese maids.

When the election results became known, one said to me: "Now that your father is prime minister, we ought to call you 'Big Little Mistress'".

I replied: "It is my father who is prime minister, not me. Please call me by my own name."

My parents always emphasised to my siblings and me that we should not behave like the PM's children. As a result, we treated everyone - friends, labourers and Cabinet ministers - with equal respect. My father's security officers became our friends. We called them by their personal names, and they did the same with us. One security officer who retired in 1970 still calls me Ling.

When strangers asked me who my father was, I used to reply truthfully that he worked for the Government.

I entered kindergarten just before age three. On the first day at school I was anxious and weepy. The teacher tried to pacify me by playing the piano. Eventually, she took me out of the classroom and showed me a very old cempaka tree that still bore flowers with a wonderful fragrance. I integrated into the kindergarten with no further problems, except for being naughty.

At the end of my kindergarten years, when I was nearly seven, there was a graduation ceremony, complete with mortarboard and black graduation gown. My father came to watch the graduation ceremony and had photographs taken with me by the press. My brothers and I knew even then that our father used us for larger purposes. He wanted us to be models for other children, though he never said so to us.

When I was in Primary 1, I was so far ahead of the other children that I did not listen to the teacher and became rather disobedient. At the end of the year, my teachers decided to solve my naughtiness by awarding me a double promotion to Primary 3.

As a result, I went from being top student in Primary 1 to eighth in Primary 3. From then on, I worked extremely hard, and I have at times wondered in later life whether my tenacity was the result of this double promotion.

It wasn't till Primary 6 that I again topped my cohort. At the graduation ceremony, I was asked to deliver a speech on behalf of the students, and my father turned up in his white-and-white. Even his daughter's school ceremony was for him part and parcel of nation building.

In both Nanyang Primary and Nanyang Secondary, the dress code required a skirt not more than 2.5cm above the knee, and we were required to wear our hair not more than 2.5cm below the ear. I had no problems complying with either rule. I had always wanted to get my hair cut as short as possible, and running in a short skirt would have been embarrassing.

As for languages, my father wanted me to be trilingual. So instead of geography, I studied Malay in school. I still remember Chegu Amin who came to our house to give my brothers and me tuition twice a week.

My Malay was good enough to earn me a distinction in the Secondary 4 school leaving examination. I also won a Malay essay-writing competition. My father, of course, attended the prize-giving ceremony.

I was streamed into the sciences in Secondary 3. I found my science teachers teaching us in Mandarin but using English textbooks. I thought that this was an inefficient way to teach and so switched to an English school, Raffles Institution, for my pre-university education.

I chose RI, not National Junior College, because NJC, then new, had poached the best teachers from other schools, and had the best facilities. I have always had a sense of reverse snobbery, and so chose RI.

In my first year in Pre-U, the school was still at its old Bras Basah address. At that time, I already had a black belt in karate. In one sparring session, when I blocked a kick, my block was slightly off and so the impact of the kick was felt in my metacarpal bones. It was rather painful.

I completed the training session, went home, told my mother about the accident, whereupon she rushed me to Singapore General Hospital. The orthopaedic surgeon said there was nothing to be done about the fracture other than put on a bandage, and made light of the whole thing. But my mother ordered me to stop my karate from that day. By that time, my curricula and extra-curricular activities - which included cross-country running and swimming - were taking up so much of my time that I did not protest.

In my second year in Pre-U, the school moved to its Grange Road site. The buildings were bigger and brighter, and there was no longer any danger of the roof suddenly collapsing on us. But most of us had on our minds the A-level exams that we had to sit at the end of the year.

I had always been a consistent student, not the type who studied at the last minute. Still, my self-confidence was low, and after every single paper, I imagined that I had done poorly.

After the exam, I travelled with my parents and my brother Hsien Yang to Britain, France and Egypt. The trip was great fun, except that I woke up every morning dreaming that I had failed all my papers.

The results came out in early 1973. To my astonishment, I had topped my science cohort for the whole of Singapore. I was awarded the President's Scholarship.

My mother advised me: "Take the prestige. Don't take the money, so you won't be bonded."

My father said: "No, take the money. It makes no difference whether you are bonded or not."

So I took the money, which was then only enough to cover the fees at Singapore University, with a couple of hundred dollars left over for pocket money.

I enjoyed my childhood and adolescence. My parents were firm but never put pressure on us to perform well. I studied hard and trained hard, not because my parents told me to, but because I wished to. In fact, they often tried to persuade me to ease off.

I take after my father in this respect. Indeed, he often chastises me for being even more intense than he is. He once told me: "Your misfortune is that you have my genetic traits, but in so exaggerated a form that they have become a disadvantage for you."

Well, there is nothing I can do about that.