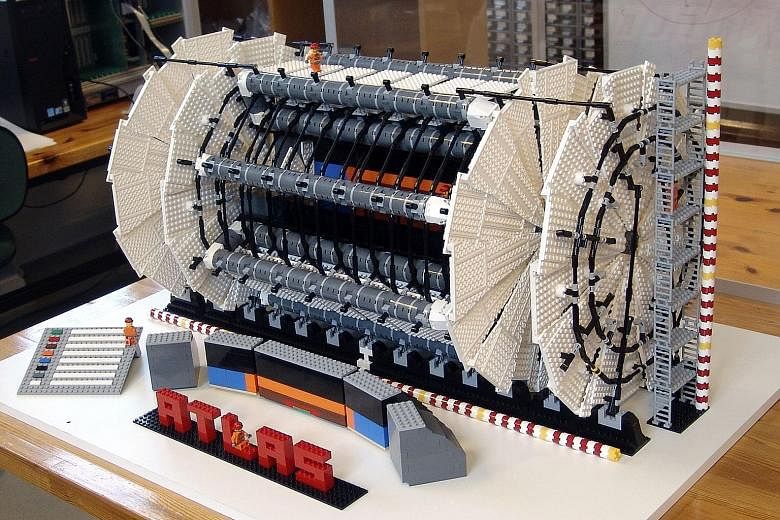

Whether you are a child or an adult, the sight of a 9,500-piece Lego scale model of one of the largest and most sophisticated scientific instruments in the world is sure to fire your imagination. Especially when it looks almost as hard to put together as the real thing.

It is a testimony to the object's beauty and significance to society, because only extraordinary things command extraordinary numbers of Lego blocks.

As for the machine which inspired the Lego work, a vast amount of brain power went into it.

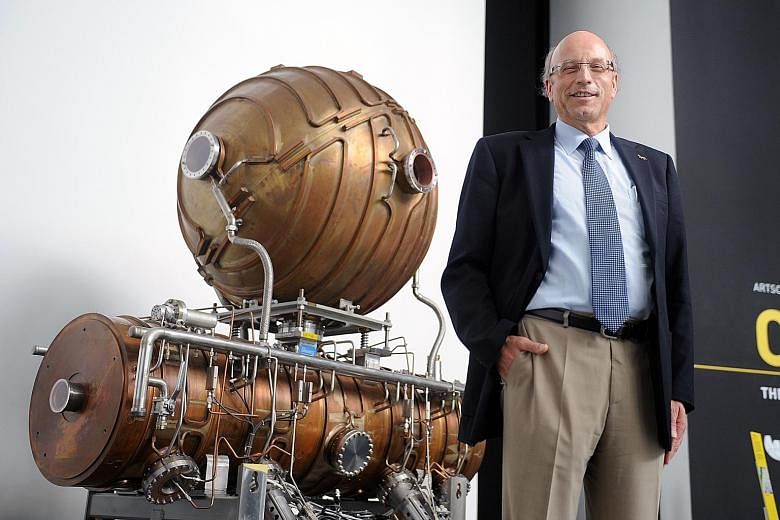

"The ideas were not the work of a single person," renowned Swiss physicist Peter Jenni tells The Straits Times, as he proudly shows photos of both real and Lego versions of Atlas, a 46m-by-25m monster machine residing 100m below the ground on the border between France and Switzerland.

Atlas may be big, but it is part of something much bigger: the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), an underground tunnel 27km long that goes in a circle and uses incredibly powerful magnets to accelerate subatomic particles to 99.99999999999973 per cent of the speed of light.

When two beams of particles travelling at this speed smash into each other, strange new particles may be produced. It is the job of Atlas, the largest of several particle detectors, to measure the characteristics of these particles in the hope of validating mind-bending theories of how matter and energy behave in the universe.

One of these new particles was the Higgs Boson, announced to much fanfare in 2012. It is this particle which gives other particles their mass.

Professor Jenni was in Singapore this month to give a public lecture at the ArtScience Museum in conjunction with an exhibition on the collider, which ended on Feb 14.

The 67-year-old is one of the veterans of this scientific research odyssey at the LHC that is coordinated by the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (Cern). He has been at Cern since the 1970s, when he arrived as a summer student, and recently retired as spokesman for the research team known as the Atlas Collaboration.

In his youth, he was among the top players on the Swiss junior national chess team, and even competed in the Soviet Union, which was known then as the land of chess masters. "But fortunately I did not do it (become a professional chess player), as it would have been very difficult to make a living."

Instead, another passion took hold when he went to university. "I was really infected by the virus of particle physics."

Prof Jenni points out, however, that a career in particle physics is not just about smashing protons and fabricating bosons that seem to have no relevance to modern-day society.

In fact, work done at Cern has transformed the world in a revolutionary - and practical - way. The World Wide Web was invented there in 1989 by Tim Berners-Lee to facilitate communication between scientists in different parts of the world. The world's very first website, set up at Cern and containing information such as researcher details, technical manuals and bibliography, has even been restored and is accessible to the public.

Furthermore, Prof Jenni says, Cern researchers have made career switches into fields as distant as finance. They take with them transferable skills prized by any global industry, such as the ability to work with people from all over the world and the skills to deal with unconventional problems, he added.

In fact, every year, the National University of Singapore sends a few students to Cern on stints of up to a year to collaborate with resident researchers on a wide range of projects, not only learning about particle physics, but also joining social activities such as board games, football matches and movie nights.

Nanyang Technological University also conducts a three-week workshop, called Particle Physics and Cosmology and Implication for Technology, every two years in collaboration with Cern and other institutions.

International collaboration played a role in the success of the LHC - where another such huge enterprise fell apart.

The Superconducting Super Collider, an 87km behemoth of a tunnel that would have been even more powerful than the LHC, was planned for Texas in the United States in the 1980s. To the dismay of the American scientific community, the project was scrapped by the US Congress in 1993 as it was deemed too expensive.

Prof Jenni explains that Cern, being run by 21 member states, would not be able to make the kind of unilateral decision that Congress did.

Today, researchers at Cern hail from almost 40 countries, ensuring that the journey of exploration and discovery crosses national boundaries and never stops.

"When you sleep, the Americans are awake and when you wake up, the Japanese are already very busy," Prof Jenni says. "It is very important that these projects are open to global collaboration."

But this is just the beginning.

Physicists like Prof Jenni are now talking about a hypothetical Very Large Hadron Collider, one that is a hundred kilometres in circumference. It would smash particles with 10 times the energy, potentially creating even heavier and more exotic new particles that could ultimately allow the human race to develop technology that even science fiction has not dreamt up, he says.

"It's really going into the unknown."

On the first conceptual stirrings of the LHC in the 1980s, he recalls: "People were saying it was crazy. But one should not give up so quickly.

"Building a machine at the edge of what is possible gives a lot of dreams to young people and encourages them to study science."