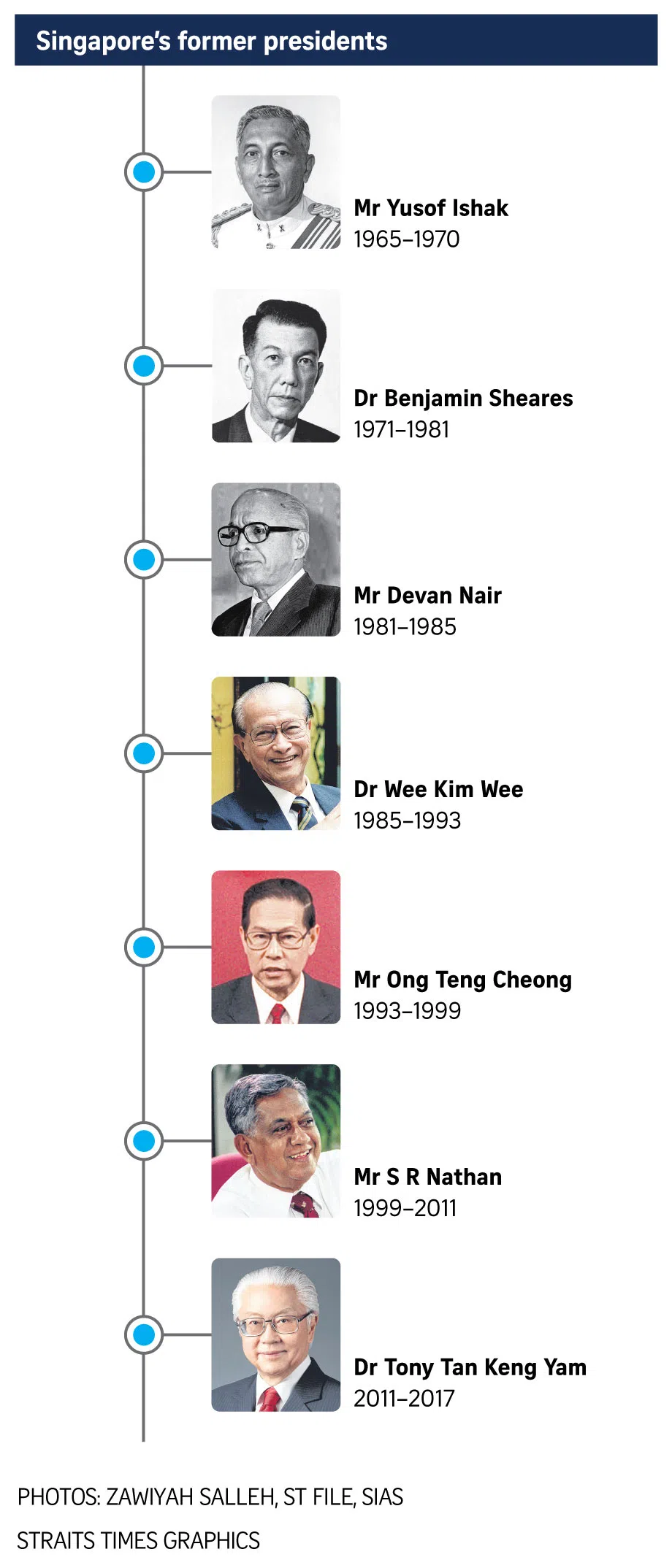

Countdown to Singapore’s Presidential Election: The who and the what

By September, Singaporeans will know who their next president is going to be. Will Madam Halimah Yacob, the nation’s first female head of state, who has served since 2017, run again? What does the role involve, and what challenges will the president face? How might this election differ from previous ones? Insight speaks to observers to find out.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Madam Halimah Yacob, flanked by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong (left) and Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon, at her inauguration as the eighth President of Singapore at the Istana on Sept 14, 2017.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Amid global uncertainty and domestic anxiety over the cost of living, the next president of Singapore must be a unifying figure in whom Singaporeans have confidence.

The job of the head of state has not changed much over the years, but people have come to expect more, observers told The Straits Times.

They said the election, which is called on a regular six-year cycle, will likely be held close to the deadline in September, after the National Day celebrations – and after the National Day Rally speech by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, usually in the second half of August.

This would be a time when issues and challenges confronting Singapore, as well as a sense of national identity and unity, would be at the forefront of people’s minds, they noted.

Issues and challenges facing Singapore

Dr Gillian Koh, deputy director of research at the Institute of Policy Studies, said that the conditions today are similar to those in 2011.

Then, people felt that the world had seen an end to the “long boom” post-World War II, and markets were anticipating another crisis in the United States and Europe which could affect Asia.

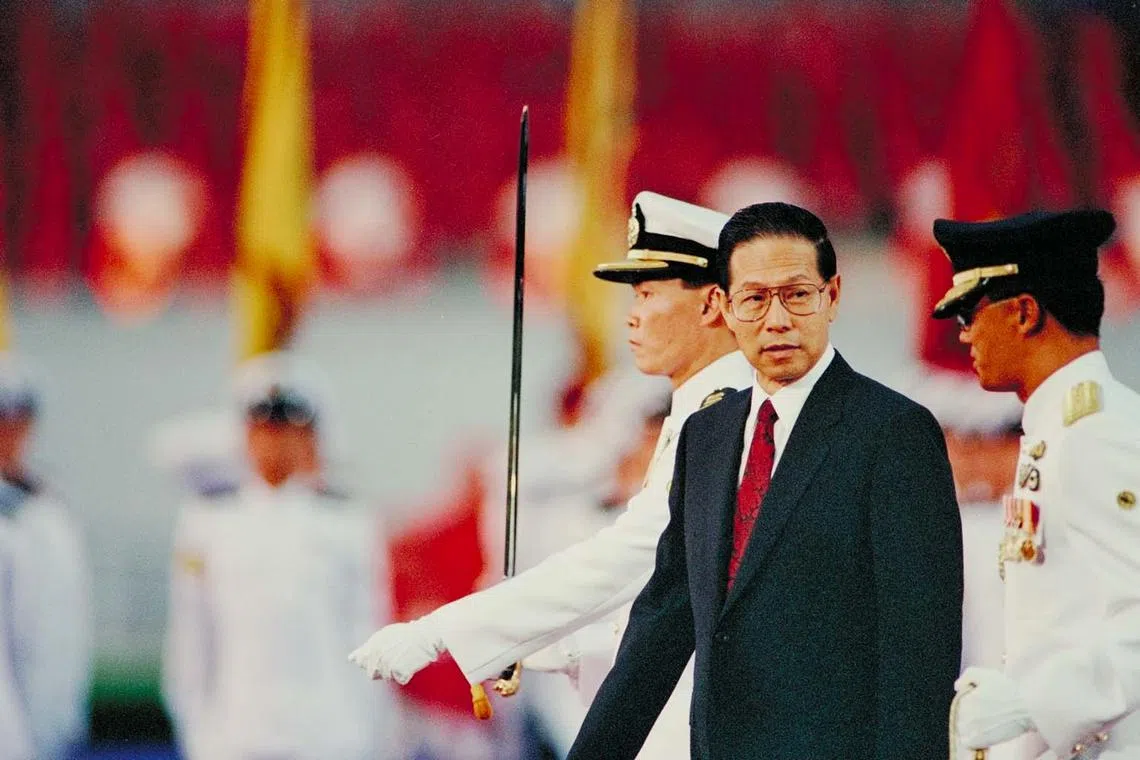

She noted that at the time, the candidate who eventually became president – former deputy prime minister Tony Tan Keng Yam – said he envisaged that the Government would make contingency plans, and gave the assurance that he would protect the national reserves with great care.

Similarly today, Singapore and the world face a tangled web of challenges – from US-China rivalry Russia-Ukraine war his speech during the debate on the President’s Address in April.

Hence, the upcoming election will involve choosing a candidate with experience, and who has a calming and steady temperament in crises, said Dr Koh.

National University of Singapore (NUS) sociologist Tan Ern Ser said it is not the president’s responsibility to directly address problems such as the economy and inflation, or geopolitical challenges, as these are the responsibilities of the prime minister and his Cabinet.

Instead, he said, the president should rally Singaporeans to stay socially cohesive and resilient amid external or internal threats, while keeping an eye on how the reserves are being used.

He added that the president could also use the prestige and symbolic power of the presidency to champion worthy causes that would enhance the well-being and unity of Singaporeans.

Dr Leong Chan-Hoong, head of policy development, evaluation and data analytics at research consultancy Kantar Public, said that in a politically divided world, the next president should also ideally have good working knowledge of foreign policy and international relations.

But one important fact remains: By design, the president has no executive, policymaking role. This remains the prerogative of the elected government that commands the majority in Parliament.

Does it mean, therefore, that the president’s role is simply rubber-stamping?

President Halimah Yacob’s tenure has shown otherwise, said political analyst and Nanyang Technological University (NTU) associate lecturer Felix Tan.

He said there has been some evolution in the “soft power aspect” of the role, with the President showing that she can still be involved in engaging with Singaporeans and championing certain social causes.

For example, she has spoken up on violence against women

Role of the president

The Constitution clearly defines the role and scope of the president to have custodial powers, but not executive ones.

Discretionary powers

He or she can veto or block government actions in specific areas such as the protection of past reserves, appointment of key personnel, Internal Security Act detentions, Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau investigations and any restraining order in connection with the maintenance of religious harmony.

The Council of Presidential Advisers (CPA) advises the president on the use of such discretionary and custodial powers.

The CPA consists of eight members and two alternate members, who are appointed by the president or nominated by the prime minister, the chief justice and the chairman of the Public Service Commission. All nominations to the CPA are approved by the president.

It is obligatory for the president to consult the council when exercising her discretionary powers related to all fiscal and appointment matters.

Non-discretionary powers

On all other non-discretionary matters, the president must act in accordance with the advice of the Cabinet, or a minister delegated with that power.

The president will meet the prime minister regularly to discuss a wide range of issues and share his or her views, though such discussions are kept confidential.

In a 2011 statement, Law Minister K. Shanmugam explained the role of the elected president, saying: “The president’s veto powers are an important check against a profligate government squandering the nation’s reserves, or undermining the integrity of the public service.

“That is why the president is directly elected by the people: to have the mandate to carry out his custodial role, and the moral authority to say no if necessary to the elected government.”

President Ong Teng Cheong was the first elected president.

PHOTO: ST FILE

In addition to constitutional duties, the president also has ceremonial and community-related ones.

For example, he or she presides over the National Day Parade, opens each session of Parliament, and officiates at swearing-in ceremonies of key appointment holders such as the prime minister, Cabinet ministers, chief justice and Supreme Court judges.

The president also supports various causes, including volunteerism, social entrepreneurship, sports, culture and the arts.

This could be through the President’s Challenge, or the various awards that the president lends his or her name to, such as the President’s Scholarship or President’s Award for Teachers.

He or she also hosts state visits from foreign dignitaries, and the presentation of credentials by foreign diplomats.

The elected presidency

The elected presidency – where the president is elected by the people to safeguard the nation’s reserves and assets, and protect the integrity of the public service – was first broached by then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in 1984 during a walkabout in Tanjong Pagar constituency.

Singapore held its first presidential election in 1993. There have been four elected presidents – Mr Ong Teng Cheong, Mr S R Nathan, Dr Tony Tan Keng Yam and the incumbent, President Halimah Yacob.

The election in 2011 was the most contested one with four candidates – former deputy prime minister Tony Tan, former People’s Action Party MP and now Progress Singapore Party chairman Tan Cheng Bock, former civil servant and Singapore Democratic Party member Tan Jee Say and former NTUC Income chief executive Tan Kin Lian.

The most recent 2017 election was a walkover for Madam Halimah

The most recent 2017 election was a walkover for Madam Halimah as there were no other qualified Malay candidates eligible.

PHOTO: LIANHE ZAOBAO FILE

It was a reserved election for a particular ethnic community – in this case, Malay – as the community had not had a member elected as president in the past five terms.

Before Madam Halimah, the country had not had a Malay president since Mr Yusof Ishak held the post from 1965 to 1970.

Constitutional amendments were passed in November 2016 to reserve the elected presidency for candidates of a particular racial group if there has not been a president from the group for the five most recent presidential terms.

Who are Singaporeans looking for?

Observers pointed out that some Singaporeans may want or think of the president as an executive president, even though this is not his or her role as defined by the Constitution.

The president is not a “check” on the government of the day, they said.

Explaining why this misconception persists, former nominated MP Zulkifli Baharudin said it is precisely because the requirements for candidacy are stacked so high that some may expect their president to not just have ceremonial and custodial powers.

People will want to elect a person who “bears the conscience of Singapore” and who can reflect their hopes and fears, he added.

Where the line between the presidency and politics blurs is when some Singaporeans desire a more representative Parliament with more opposition, and reflect that sentiment in voting for their preferred presidential candidate.

“This reflects the evolving infancy of the institution of the elected presidency, as we will have to see if people understand the role of the president, or if Singapore should go back to the appointed presidency system,” said Mr Zulkifli.

President S R Nathan served two terms in office, from 1999 to 2011.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Dr Koh said a key worry would be if Singaporeans are not paying much attention to the presidency and the election. If so, given the short campaign time, they may take shortcuts and vote by who they identify with by race, religion or any past political affiliation, rather than by understanding the office and candidates in detail.

As Mr Ho Kwon Ping and Mr Janadas Devan said in a 2011 Straits Times op-ed, “depending on the calendar, each presidential election will either be a curtain raiser for a general election or a continuation of one”.

The reality is this: It may be increasingly difficult for some Singaporeans to not vote with their wish for more political contestation in mind.

Could the presidential election end up being an early referendum on the ruling party, ahead of the next general election due by 2025?

Dr Leong said: “The challenge for this election is how to ensure that candidates who step forward understand the bread-and-butter issues on the ground, are trusted partners with the elected government and, importantly, are not seen as overly pro-establishment by the public.”

He observed that based on the last two presidential elections, a candidate’s political background is a key consideration for voters, who have shown their liking for an independent candidate, not a former Cabinet minister.

For example, the presidential election of 2011 was a battle between the four “Tans”: Dr Tan Cheng Bock, Dr Tony Tan, Mr Tan Jee Say and Mr Tan Kin Lian.

It was a close fight between the first two. In the end, Dr Tony Tan, who had been a Cabinet minister, won – but by a narrow margin of 7,382 votes.

President Tony Tan Keng Yam contested and won the 2011 election.

PHOTO: ST FILE

One-quarter of the voters chose Mr Tan Jee Say, who argued that the president should act as a check and balance on the Government.

The Government is likely to understand that Singaporeans do not like being told how to vote for a non-partisan office, and may avoid endorsing any candidate openly, Dr Leong added.

NUS’ Associate Professor Tan said the upcoming election is likely to remain highly contested, and candidates will have to find a balance between emphasising that they can effectively take a “checks and balances” role where they are allowed to, and not assuming the role of an opposition.

They will also have to display their relevant experience in key positions in the economy or society, he said.

“They would also have to come across as authentic, personable, sincere, rational, responsible, informed, serious-minded, presidential and certainly not someone with an axe to grind – and be perceived as someone who could take an independent stand, as and when necessary.”

Could the election be held after September?

While Sept 13 is the deadline – this is when Madam Halimah’s term expires – there is a chance the election could still be called after Sept 13.

To understand why, one has to look back to 2017, when the term of presidency at the time was set to expire on Aug 31.

To give more time for changes to the election process, and to avoid having the presidential election campaigns during National Day celebrations, then Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office Chan Chun Sing said the Government would adjust the timing of the polls.

A writ of election was issued later in August – before the Aug 31 expiry date – with a potential polling day in September. But that eventually did not happen as Madam Halimah went uncontested.

At the time, Mr Chan said the Attorney-General had advised that there could be an interval between when the incumbent’s term expires, and when the new president assumes office.

The Constitution provides for an acting president, until a new one is elected and takes office.

Mr Chan had also said that as this arrangement could not go on indefinitely, the period in which the acting president shall exercise the functions of the office of the president should not exceed one month.

Hence, the very latest that the polls can be called this year would be on Oct 13.