Nobel laureate Barry Marshall drank bacteria culture in 1984 to prove link to gastric ulcer

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Professor Barry Marshall preparing H.pylori cells on a microscopic slide.

PHOTO: THE MARSHALL CENTRE

SINGAPORE - While it is commonly known today that gastric ulcers are usually caused by an infection from a specific type of bacterium, less is known about the scientist who helped discover it, and his unorthodox quest to prove it.

Back in 1982, when Professor Barry Marshall was a trainee doctor at the Royal Perth Hospital in Australia, he learnt that Dr Robin Warren, a pathologist there, had found that biopsy samples from patients with gastric ulcers contained traces of a spiral-shaped bacterium known as Helicobacter pylori.

"At that time, the discovery was unprecedented, given that gastric ulcers had in the past been associated with stress or lifestyle choices, and was thought to be a chronic disease," Prof Marshall told The Straits Times in an interview over Zoom last Tuesday (Jan 11).

Prof Marshall is one of the 21 scientists and Nobel laureates attending the Global Young Scientists Summit, hosted by the National Research Foundation, this week.

In addition, it was thought to be impossible for bacteria to survive in the inhospitable lining of the stomach, given that stomach acid has a pH of 1.5, making it about 10 to 20 times more acidic than lemon juice.

Intrigued, Prof Marshall was determined to find out if the bacteria was significant in causing gastric ulcers, and decided to join Dr Warren on his research.

Together, they conducted a study of biopsies from 100 patients.

Bacteria were present in almost all patients with gastric inflammation, duodenal ulcers (an ulcer that develops in the first part of the small intestine) or gastric ulcers.

"But here's the thing... successful infections don't kill you. They just live there on your body so that you can spread it to everybody else, much like the Omicron variant.

"Eighty per cent of the people (infected with) the Helicobacter bacterium never used to get sick from it, and they might just spread it to other family members, for example," said Prof Marshall.

"It got a bit confusing because we found that a lot of people who had the stomach bacteria seemed to be quite well, and 80 per cent of people who had it didn't get ulcers or stomach cancer until much later," he added.

"So when we published this idea in 1983 that the bacterium could be cancer-causing, people didn't believe it because it was too common," Prof Marshall, 70, said.

When they tried to present the research paper at a gastroenterology meeting, they were rejected and told by the judges that it was "shameful" to produce research like this.

H. pylori, which is generally more prevalent in developing countries, is estimated to be present in around 50 per cent of the world's population.

In Singapore, up to 31 per cent of people are infected with the bacterium, the majority of whom do not experience any symptoms or complications, according to the National University Health System's website.

In order to convince sceptics and to prove the link between the two, Prof Marshall drank a culture of the H. pylori bacterium.

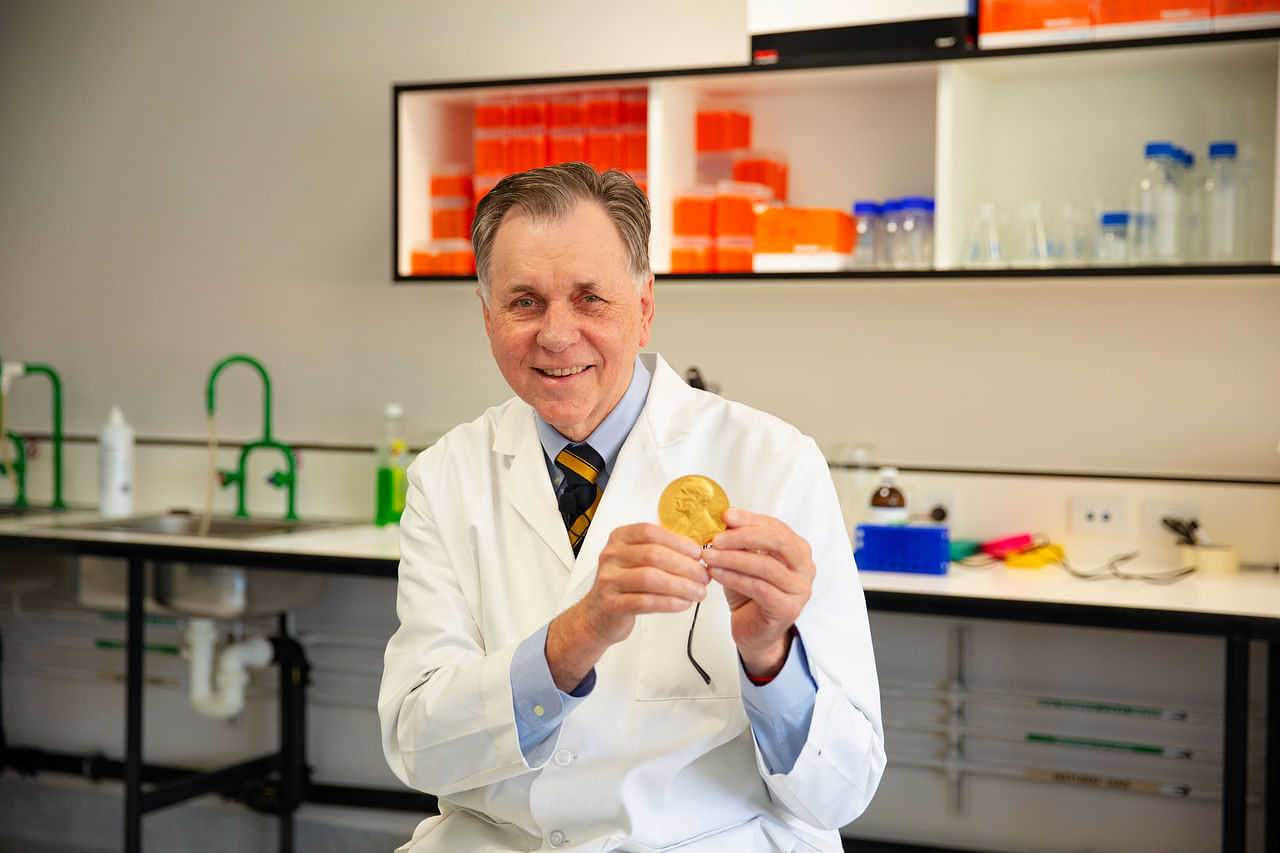

Professor Barry Marshall holding his Nobel prize medal.

PHOTO: THE MARSHALL CENTRE

A few days later, he developed gastritis - the precursor to an ulcer - and when he biopsied his own gut, he was able to prove that the H. pylori bacterium was, indeed, the underlying cause of his ulcer.

People began to take an interest in the experiment after it was published in the Medical Journal of Australia in 1985, recalled Prof Marshall, as there had been epidemics of gastric disease reported for about 20 to 30 years - though it had not been understood that the bacterium was causing them.

For their tenacity in challenging the prevailing dogma, Prof Marshall and Dr Warren received the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 2005.

"And then it took about 10 years before we found out the best treatments for H. pylori," added Prof Marshall, who is a clinical professor at the University of Western Australia and a specialist gastroenterologist.

Treatment for the H. pylori infection typically consists of taking stomach acid blockers known as proton pump inhibitors, along with two antibiotics, which has a 90 per cent cure rate in patients, he noted.

Given that H. pylori could mutate, it is possible for certain bacterial mutations to be resistant to certain antibiotics, thereby underlining the role of precision medicine, said Prof Marshall.

For instance, certain DNA techniques could identify the particular strain of bacterium, which would in turn inform doctors on the right antibiotics to use, he noted.

However, some believe that an H. pylori infection could potentially be useful too, especially in people who have had the infection since childhood, as they are less likely to have diseases of the immune system such as asthma, eczema and other allergic reactions, added Prof Marshall.

He has founded a company - Australian biotech start-up Ondek - which is looking at producing the H. pylori bacterium in a dry form that "isn't infectious and is completely harmless" when consumed.

The product could be taken as a food supplement to help to reduce the activity of those who may have overactive immune systems, which could help with asthma or allergies, he said.