Medical Mysteries

My eyes bulge, I see double, I do not feel right: It could be thyroid eye disease

Medical Mysteries is a series that spotlights rare diseases or unusual conditions.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Madam Goh Sock Cheng (left) and Mr Yeow Ming Kon (right) with Dr Blanche Lim (second from left) and Adjunct Associate Professor Gangadhara Sundar of NUH's ophthalmology department.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

SINGAPORE – In September 2022, Madam Goh Sock Cheng started seeing things around her in two-dimensional form, or 2D.

When in a crowd of people, for example, she could not perceive depth. And when she walked into a shopping mall or supermarket where the lights were bright, her vision became a mess, she said.

“I forgot what 3D looked like after a while,” added the palliative nurse. “It was not the usual way of looking at things any more. It was very confusing and very glaring. Sometimes I would use just one eye to look at an area before I headed there.”

Madam Goh, now 62, had thyroid eye disease (TED), a rare autoimmune disease in which the eye muscles and fatty tissue behind the eyes become inflamed, pushing the eyes forward or causing the eyes and eyelids to become red and swollen.

In some individuals, the eyes end up being out of line, leading to double vision. In rare cases, TED can cause blindness from pressure on the nerve in the back of the eye or ulcers that form on the front of the eye.

The incidence rate of TED is approximately 19 out of 100,000 people a year globally. In Singapore, according to the National University Hospital (NUH), TED has a prevalence of 1 per cent to 2 per cent in the population, or an annual incidence of between 30 and 50 cases per 100,000 people.

Despite having the word “thyroid” its name, about 30 per cent of TED patients do not have any thyroid disease but still developed TED, said Adjunct Associate Professor Gangadhara Sundar, a senior consultant with the Department of Ophthalmology at NUH.

That is one reason why the condition usually gets misdiagnosed as allergic conjunctivitis or dry eyes.

Prof Sundar also said not everybody with TED displays redness through the skin, especially not Asians, who tend to be darker-skinned.

When TED is diagnosed early, mild cases are treated with artificial tear drops to relieve dryness of the eyes. But when it is detected late, surgery is needed.

Surgical procedures could include orbital decompression to remove bone and soft tissue from behind the eye to create more space; strabismus or eye muscle surgery to treat misaligned eyes; eye muscle resection to correct severe double vision; and eyelid surgery to improve the appearance and function of the eyelids.

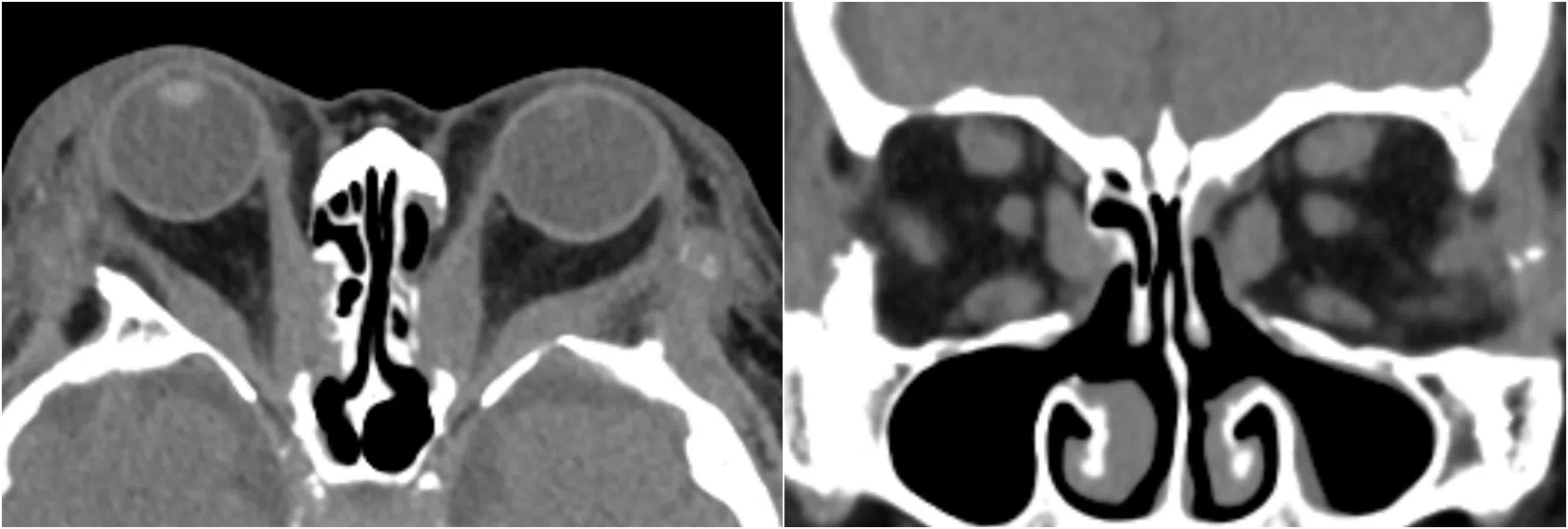

Scan showing a thyroid eye disease patient’s eyeballs bulging out of the eye sockets (left). Working through the nose, surgeons use endoscopes and small instruments to carry out decompression surgery, removing the middle and bottom walls of the bone surrounding the eye (right).

PHOTOS: NUHS

At NUH, a dedicated TED clinic handles around 50 newly diagnosed and referral cases yearly, from Singapore and the South-east Asian region. Patients include children and adults.

Madam Goh told The Straits Times that her eye condition came on very suddenly.

“The words on the computer seemed blur to me, and I wondered how my vision had deteriorated so fast,” said the grandmother of two.

“(On one occasion) I had to light a candle, but because the light was dim, I could not target the wick. My colleague had to help me.”

Her colleagues were also concerned that her eyes looked swollen.

Madam Goh Sock Cheng had thyroid eye disease, an autoimmune disease in which the eye muscles and fatty tissue behind the eye become inflamed (left). After decompression surgery, where part of the walls of her eye sockets were removed, she still had crossed eyes (right), and went through another operation to straighten the eyes.

PHOTOS: NUHS

Said Madam Goh: “My eyeballs had already started to have squints, being pulled to one end. I also could not distinguish between the colours red and black.”

Thinking her spectacles, which were made about five years earlier, could be the problem, she got a new pair.

When that did not help, she decided to see an eye doctor, who then told her she was suspected of suffering from TED and immediately referred her to his colleague who specialises in the condition.

“She told me I had to go for a decompression operation, but I had some insecurities then, so I decided to seek a second opinion at NUH,” said Madam Goh.

In August 2023, she underwent two operations to correct her misaligned eyes.

“The first thing after the surgery was that I realised there was depth in the sink in my house. It had been a long time since I saw the depth,” said Madam Goh, laughing.

Unlike her, retired glass contractor Yeow Ming Kon, 66, did not have the textbook signs of TED – the bulging eyes and intermittent wide-eyed stare.

Instead, he had severe eye pain and swelling – “it felt like there was sand constantly in my eyes”. His facial appearance also changed drastically, with a slanted left eye and severely droopy and puffy eyelids.

Retired glass contractor Yeow Ming Kon did not have the textbook bulging eyes, a typical sign of thyroid eye disease. Instead, he had severe eye pain and swelling. His facial appearance changed drastically, with a slanted left eye and severely droopy and puffy eyelids.

PHOTO: NUHS

“There was once a child who became so afraid after looking at me that he started crying. I felt so bad after that, I went out only when I needed to,” Mr Yeow said.

That was in mid-2018.

“At that time, I had no appetite and was losing weight. I went from 82kg to 51kg in less than a month. My friends sensed something was wrong and insisted that I had better see a doctor,” he said.

After a battery of blood tests, he was referred to Prof Sundar and was then told that he had TED.

Said Mr Yeow: “By the time I saw Prof Sundar, I was almost blind. There was a black patch right in the centre of my sight and I was told I needed an operation.”

He decided to shut his business for good and retire.

“I made sure I finished all my projects, sold the business and used the money to pay my workers and sent them home. I was already nearing 61 and intended to retire. I did not even dare drive,” he told ST.

But Mr Yeow had other medical issues.

Said Prof Sundar: “We had to call in the neurologist, and Mr Yeow later developed pancreatitis. His double vision became the least of his worries, as the rest had to be sorted out. He had seven operations in all to save his life.”

Although his vision and appearance have significantly improved, Mr Yeow continues to wear specialised lenses and adapts to lingering double vision. Despite the challenges, he remains deeply grateful to the NUH team.

“At least I can continue cooking for my wife, something I enjoy doing very much,” he said.