Muscles, fats and simple blood test can predict menopausal women’s health

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

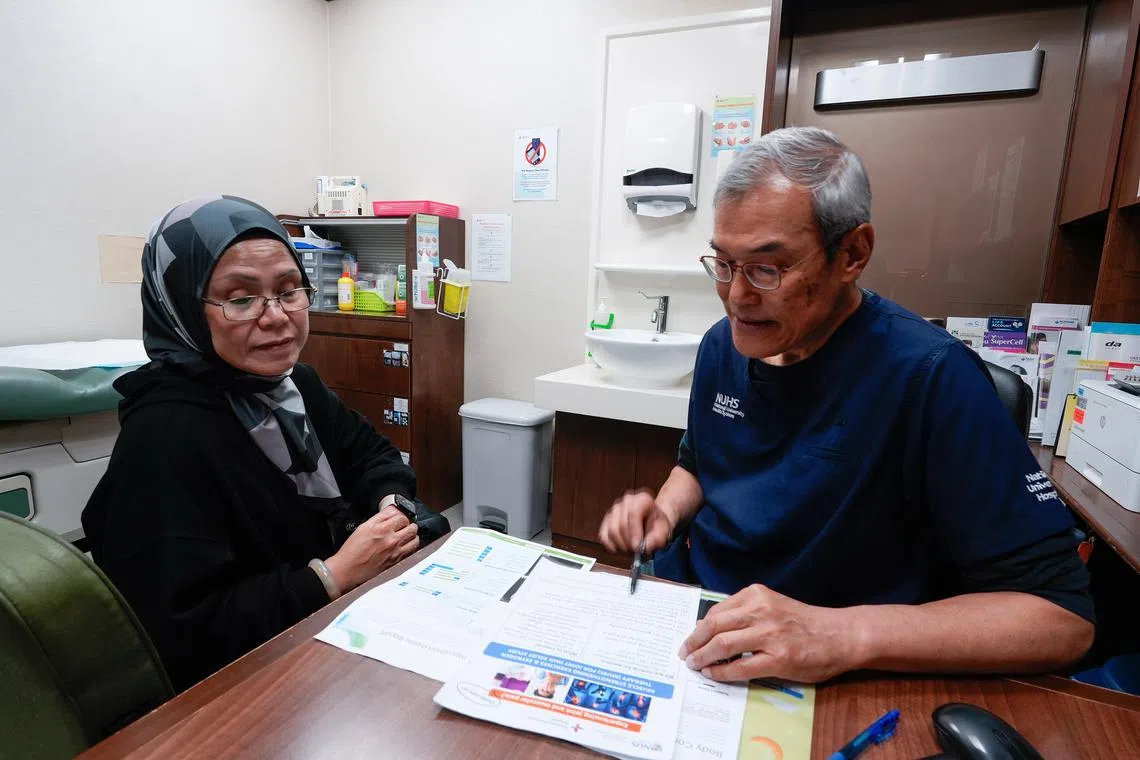

Madam Sabarina Jumarudin, a participant of the Integrated Women’s Health Programme at NUH and the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, with IWHP lead Yong Eu Leong.

PHOTO: NUHS

SINGAPORE – A simple blood test can predict which woman will have less muscle and will be walking more slowly later in life.

It is also practical and cheaper than current methods of measuring muscle, such as the current gold standard magnetic resonance imaging scans or strength tests, which are also more time-consuming.

This new insight from a longitudinal cohort study of midlife women in Singapore shone light on how muscle strength, visceral fat and their association with physical decline after menopause can potentially lead to downstream health impacts among women here.

Researchers from the National University Hospital (NUH) and National University of Singapore (NUS) found that women with a lower creatinine-to-cystatin C ratio (CCR) – a marker derived from blood tests – had less muscle and walked more slowly as they age.

Creatinine is a by-product of normal muscle function and energy use, and a higher level indicates higher skeletal muscle mass or poor kidney function.

Cystatin C is a protein produced by the body’s cells that is filtered out by the kidneys. A normal cystatin C level rules out poor kidney function.

A low CCR of under 8.16 was associated with a lower muscle volume of 0.35 litres in the thigh, and a slower gait of 0.049m a second.

This suggested that CCR could be a useful early warning sign for age-related muscle loss, which may lead to falls, frailty and reduced quality of life.

The findings were published in Menopause, a monthly peer-reviewed journal, in March.

The scientists involved in the study are from the Integrated Women’s Health Programme (IWHP) at NUH and the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine.

The IWHP was initiated to identify and address the healthcare needs of midlife Singaporean women. It recruited a cohort of 1,200 Chinese, Malay and Indian women aged 45 to 69 between 2014 and 2016 – about 70 per cent of whom were post-menopausal. Their health metrics were then tracked over time.

In the first study based on this cohort, published in international journal Maturitas in October 2023, the researchers shared a ranking of menopausal symptoms – with joint and muscular discomfort

Called arthralgia, it had moderate or severe impact on a third of the midlife women of the cohort.

A subsequent study, published in the Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism journal in October 2024, found that women with both weak muscle strength and high levels of visceral fat – the deep belly fat around the internal organs – had the highest risk of developing prediabetes or type 2 diabetes.

Their risk was 2.63 times higher than that of women who had normal muscle strength and lower fat levels.

Having just one of these conditions also increased their risk, though to a lesser degree. The risk from having high visceral fat alone is 1.78 times higher. Among those with weak muscle strength, women with high visceral fat faced 2.84 times as much risk compared with those with low visceral fat.

Explaining the impetus for the study, IWHP lead Yong Eu Leong said: “Muscle... burns up fat. What about those who have weak muscles? Does it affect the risk for diabetes in the future?”

The cohort’s initial muscle and visceral fat measurements served as a baseline for researchers to track changes over the years.

Researchers then analysed how changes in fat and muscle measurements taken about six years later – by then, about 90 per cent of the women were post-menopausal – related to whether women had developed diabetes.

Professor Yong, who also heads the division of benign gynaecology in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at NUH, noted that a large proportion of women in Singapore are “skinny fat”, where their body mass index is within the normal range, but that they have high levels of visceral fat and low muscle mass.

“One way (to know what your risks are) is to measure your walk and the speed at which you walk. If you cannot walk fast and straight, then your health is not so good. We wanted to see if we can develop a test that can predict gait speed. We wanted to look at molecules that actually measure muscle functions,” he said.

“These findings validated our previous (IWHP) research that showed that women should not just focus on weight loss, but on building muscle strength through exercise for diabetes prevention,” Prof Yong said.

One participant of the IWHP, administrative assistant Sabarina Jumarudin, is living proof of the findings.

The 59-year-old grandmother used to weigh 93kg and suffered from sleep apnoea.

Since undergoing bariatric surgery at NUH in 2018, a procedure that modifies the digestive system to help people with obesity lose weight, she has lost more than 30kg.

Mindful of keeping her weight down, Madam Sabarina walks to the MRT station every day instead of taking the shuttle service, and takes the stairs instead of the escalator to catch the train.

“On my way home, I usually take a longer route to ensure I clock at least 10,000 steps a day, and practise stretching and breathing exercises to strengthen my core,” she said.

“I realised that small but consistent changes do make a big impact on my health, so I do what I can on a daily basis, and it gives me confidence to not only stay healthy physically and mentally but also stave off diabetes,” she added.