Murder, we wrote: Chronicling Singapore’s underbelly over the years

From bloodstained alleys to courtroom showdowns, the city’s underbelly has been well chronicled.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

A staple of the newspaper, crime coverage in The Straits Times evolved alongside the crimes themselves.

PHOTO: ADOBE STOCK

On the night of May 19, 1934, tailor’s assistant Kong Wan San was found in Wilkie Road, bleeding from a gunshot wound.

He had been shot while entering a coffee shop at the junction of Armenian Street and Loke Yew Street. Remarkably, Kong managed to stagger out and hail a rickshaw to his employer’s house in Wilkie Road, where he collapsed. He was rushed to Tan Tock Seng Hospital but died the next day.

In his final hours, Kong told police he had been shot while walking on the street. Investigators floated the theory that the wound had been self-inflicted. The doctor who examined him disputed this, saying the trajectory of the bullet made this unlikely.

Witnesses gave conflicting accounts of what happened. Some said more than one shot was fired and others said Kong had been seen with a companion. Police began to suspect secret society involvement.

The mystery deepened over the weeks but no one was charged. In mid-June, the coroner ruled Kong’s death a murder, but the case remained unsolved.

A staple of the newspaper, crime coverage in The Straits Times evolved alongside the crimes themselves.

In colonial Singapore, guns and knives were common murder weapons. The rise in gun violence led to the introduction of the Arms Offences Act in 1973, which criminalises the illegal possession, trafficking and use of arms and ammunition and imposes severe penalties, including the death penalty for certain offences.

Violent outbursts weren’t confined to the streets.

Way back in February 1875, a mutiny erupted at a gaol located between Victoria Street and Bras Basah Road. Dozens of inmates overpowered guards, climbed over the walls and caused injuries and deaths. Crowds gathered outside the prison as soldiers were called in to restore order. The Straits Times, in a front-page article on Feb 20, 1875, documented the chaos and later called for better security and stricter discipline within prisons.

As society changed, so did its crimes. Gang fights and piracy have faded. Now, online scams and cybercrimes pose greater threats.

Another change occurred in 1969, when jury trials, a feature of Singapore’s legal system during British rule, were abolished by an amendment to the Criminal Procedure Code. Then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew said that juries could be swayed by emotion and lacked the training to evaluate complex cases.

What has not changed, however, is the media’s role in reporting crime.

Deputy news editor Melvinderpal Singh, 58, says an underappreciated value of crime reports is that they give voice to victims, to not only present a more complete picture but also aid in their recovery.

Crime reporting is also bound by ethical responsibilities.

As crime correspondent David Sun, 33, explains: “The guiding principle is to report the facts accurately while minimising harm.”

Details are handled with care, especially when children are involved.

These journalism standards have been especially vital over the years for cases that gripped the nation because of their depravity.

Convicted without a victim’s body

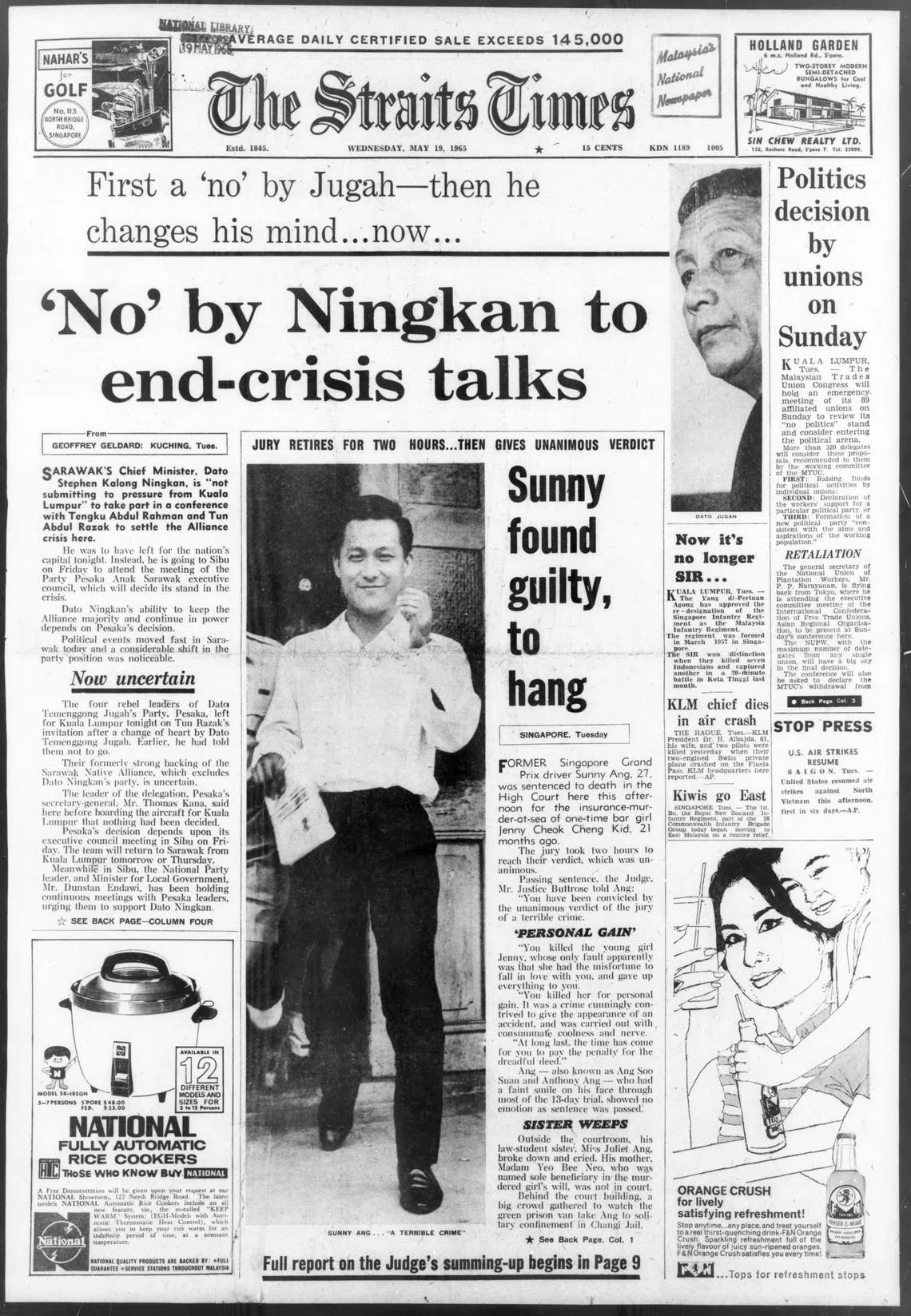

An article on May 19, 1965, about Sunny Ang Soo Suan being convicted of murdering Ms Jenny Cheok Cheng Kid and sentenced to hang. The conviction was based entirely on circumstantial evidence as the body was never found.

PHOTO: ST FILE

There was not an empty seat in the public gallery at the High Court on the afternoon of May 18, 1965. Even the court’s short aisle was filled, and no one got up during the lunch hour, to avoid losing their seats.

All eyes were on Sunny Ang Soo Suan as the 27-year-old was convicted of murder by the jury and sentenced to hang by the judge. This had been one of Singapore’s most sensational murder convictions, based entirely on circumstantial evidence as the victim’s body was never found.

The Straits Times provided extensive coverage, writing more than 50 articles throughout the trial. The lead reporters were T.F. Hwang and Jackie Sam.

The case first appeared in the paper on Aug 30, 1963. The short story reported that a girl had gone missing while on a diving trip with her boyfriend.

Ang, a former Singapore Grand Prix driver and part-time law student, and his girlfriend, Ms Jenny Cheok Cheng Kid, a waitress with little education, had hired boatman Yusuf Ahmad to take them to the Sisters’ Islands, where they would scuba dive.

Ms Cheok, 22, was an inexperienced diver, and when she did not resurface after diving in alone, Ang had Mr Yusuf take the boat to St John’s Island to contact the police.

Her body was never found, but divers found a single flipper that had been cleanly severed. An expert witness surmised it could have caused her to lose mobility and drown in the strong currents.

On Sept 6, 1963, the paper reported that the case had been reclassified as a murder probe.

Over the next two years, reporters – and the public – followed the case closely.

Sunny Ang Soo Suan was convicted of murder by the jury and sentenced to hang by the judge in 1965.

PHOTO: ST FILE

In February 1965, the paper published the boatman’s account. Mr Yusuf said he had seen Ang tinkering with Ms Cheok’s diving tank, and did not seem at all desperate to find her.

Ang’s murder trial began on April 26, 1965. In blow-by-blow accounts, the paper kept readers informed of the substantial circumstantial evidence found.

First, Ang, a skilled diver, made no attempt to go after his girlfriend when she failed to resurface.

Second, just three weeks before, Ang had taken Ms Cheok to make a will leaving her entire estate to his mother, whom she hardly knew.

Third, the couple had previously been involved in a car crash, with Ang – a very experienced driver – losing control at the wheel. The impact was mostly on Ms Cheok’s side of the car.

The court heard how Ang had taken out insurance policies on Ms Cheok, which would benefit him and his family financially.

Prosecutor Francis T. Seow argued that if a person could not be charged with murder just because the victim’s body had not been found, killers would be able to get off scot-free by getting rid of the body. After just two hours, the jury was unanimous in finding Ang guilty of murder.

The report noted how he smiled faintly throughout his trial and showed no emotion when his sentence was passed. The paper also published photos of the crowd gathered outside the High Court and Ang being taken away in a green prison van.

On Feb 7, 1967, the paper reported Ang’s execution at 5.55am the previous day. “Calm up to the last moment and praying with prison chaplain,” the report added.

First female killer hanged

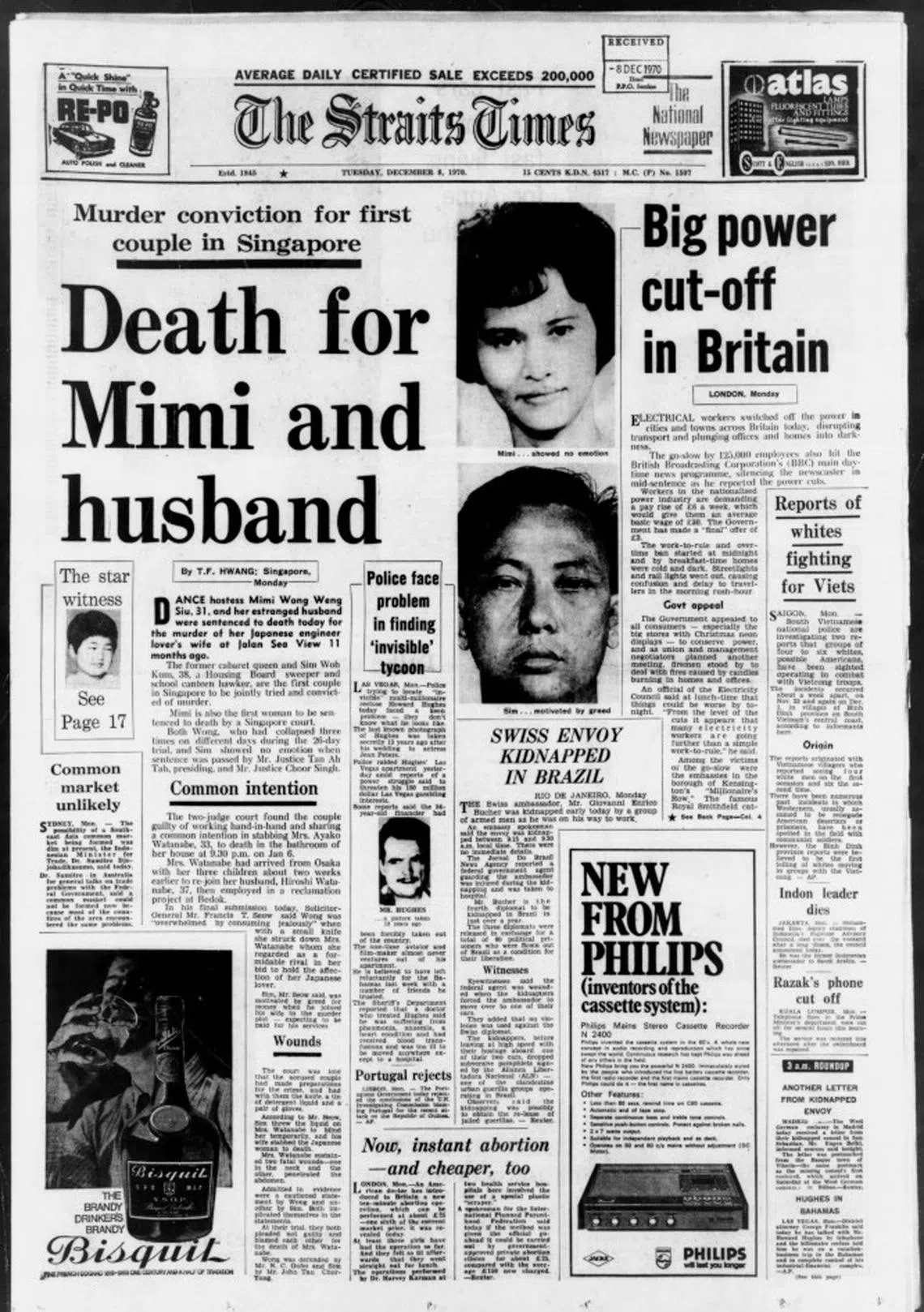

On Dec 8, 1970, the paper reported that Mimi Wong Weng Siu and her estranged husband, Sim Woh Kum, had been sentenced to death over the murder of her Japanese lover’s wife, Ayako Watanabe.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Despite collapsing three times during her 26-day murder trial, Mimi Wong Weng Siu showed no emotion when she and her estranged husband were sentenced to death on Dec 7, 1970. They were the first couple to be convicted of murder in Singapore, and she was the first female to be hanged since independence.

For months, Singapore was gripped by the sensational case with its sordid details of love, passion and infidelity.

Wong, 31, grew up poor under harsh conditions and started working in a factory at age 14. In 1956, when she was 17, she met sweeper and school canteen stallholder Sim Woh Kum, who was about seven years older.

They got married in 1958 and she had two sons with him. But the marriage was unhappy and they separated.

Wong went on to work as a cabaret girl in a bar, adopting the name “Mimi”. She was popular with her customers. In 1966, she met Japanese engineer Hiroshi Watanabe, who was posted to Singapore for work. They became intimate. But there was a problem: he was married.

Wong often lost her temper with him and was jealous of his wife, Ayako Watanabe. The situation worsened when his family moved to Singapore to join him.

To appease Wong, Mr Watanabe arranged a meeting between both women. This only fuelled Wong’s rage. Viewing Mrs Watanabe as an obstacle in their affair, she decided to get rid of her. She roped in Sim to help with the murder, promising him payment. Sim, a compulsive gambler in need of cash, agreed.

On Jan 6, 1970, Wong and Sim went to the Watanabes’ apartment, under the pretext that she had brought a repairman to fix a faulty toilet. On Wong’s instructions, Sim threw bleach into Mrs Watanabe’s eyes to blind her. Wong then stabbed her in the neck and abdomen with the knife she had brought.

The three Watanabe children were asleep in the room, but the eldest, Chieko, then nine, awoke to her mother’s screams. She ran to the bathroom to be greeted by the gruesome scene, the two killers running and her 33-year-old mother bleeding to death.

Investigations pointed easily to Wong and Sim. The crime scene left ample evidence, the affair was no secret and Chieko had seen Wong.

The Straits Times churned out articles during the 26-day trial, providing detailed accounts of each witness. Both Wong and Sim tried to shift the blame onto the other, but there was no escaping.

Mr Watanabe, who was 37 during the trial, testified that he did not dare sever ties with Wong, for she had hinted on several occasions that something terrible would befall him and his family, if he did. Even young Chieko testified, bravely recounting what she had seen that night.

Wong’s defence claimed that jealousy and heavy drinking on the day of the murders had clouded her judgment. She also claimed that Mrs Watanabe had been hostile and insulting towards her. However, these claims were disproven when a psychiatrist testified that Wong had been of sound mind during the killing.

All appeals by Wong and Sim were rejected. The pair were hanged on July 27, 1973.

Toa Payoh ritual murders

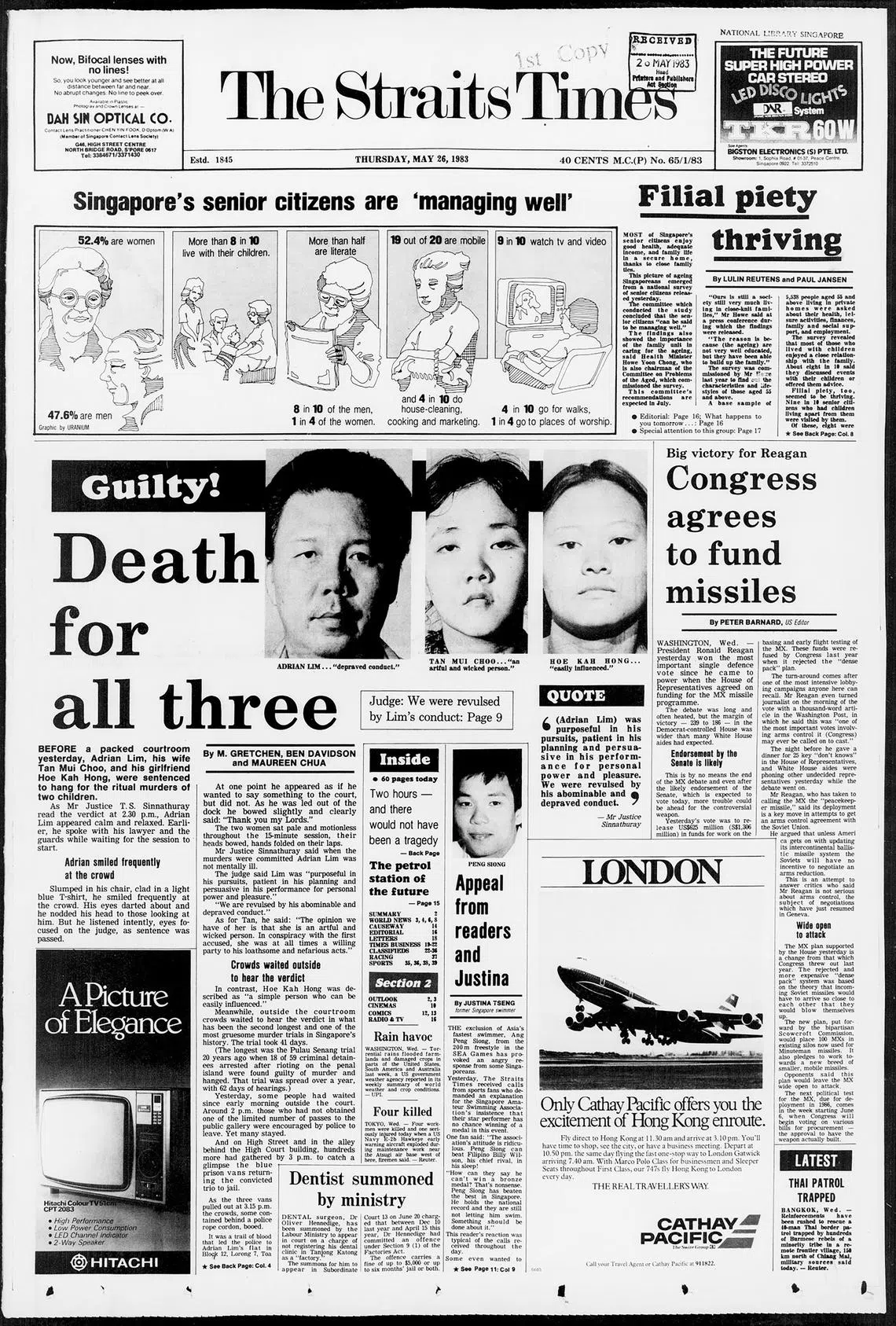

Self-proclaimed spirit medium Adrian Lim, his wife Catherine Tan Mui Choo and mistress Hoe Kah Hong were on May 25, 1983, sentenced to hang for the ritual murders of two children. The sentence was reported on Page 1 the next day.

PHOTO: ST FILE

On Nov 25, 1988, Adrian Lim, his wife Catherine Tan Mui Choo and mistress Hoe Kah Hong were hanged at dawn at Changi Prison for the murder of two children.

Their executions brought an end to one of Singapore’s most shocking murder cases – the Toa Payoh ritual murders – which had gripped the nation for years. One memorable front-page headline captured the national mood: “Guilty! Death for all three.”

The story began more than seven years earlier, with a small item published on Jan 26, 1981, under the heading “Latest”. It reported that a girl found in a suitcase the day before had been identified as nine-year-old Agnes Ng Siew Heok.

A fuller report on Page 8 gave grim details: Agnes’ body, bearing signs of sexual abuse, had been found stuffed in a suitcase outside a lift at Block 11, Toa Payoh Lorong 7.

Two weeks later, on Feb 7, the battered body of 10-year-old Ghazali Marzuki was discovered nearby. A trail of blood led police to a flat on the seventh floor of Block 12, just across the street.

Inside, investigators found religious paraphernalia, an altar and pictures of deities. The flat belonged to Lim, then 39. He lived there with Tan, 26, and Hoe, 25.

On Feb 9, crime journalist N. G. Kutty reported that police believed both children had been murdered by the same individuals, and were probing whether these were ritual killings. Police had also established that three other children were on the killers’ list to be sacrificed according to a ritual.

Notes with the children’s details were found in the flat, along with bloodstains. Lim even tried to flush a clump of hair – later confirmed to be Agnes’ – down the toilet.

The Toa Payoh flat where Adrian Lim conducted rituals and murdered two children.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The trio were arrested and questioned. Lim said in his police statement that he murdered Agnes and Ghazali to get even with the world because he was being investigated for the rape of a beautician.

They were later charged with the murder of the two children. Lim and Tan were also charged with the earlier murder of Hoe’s husband, Loh Ngak Hua, 25, who had come to the flat searching for his wife.

During the three-day preliminary inquiry in September 1981, Lim admitted to planning all three killings. A self-proclaimed spirit medium, he convinced numerous women – including Tan and Hoe – that sexual acts with him would expel evil spirits. He carried out rituals involving mock weddings, beatings and electric shocks.

As the case unfolded, Straits Times reports featured details from police, neighbours, and even a doctor who had once helped Lim draw blood from young girls.

The murder trial lasted 41 days – the second-longest trial in Singapore at the time – and was covered by journalists Ben Davidson, Maureen Chua and M. Gretchen. Crowds gathered daily outside the courthouse. Some even refused to leave after the verdict was announced.

Straits Times reporters recorded vivid details, including how Lim smiled and said “Thank you, my Lords” after sentencing on May 25, 1983, while Tan and Hoe sat pale and motionless, heads bowed. Outside, angry crowds booed as the three were driven away in police vans.

19 and a serial killer

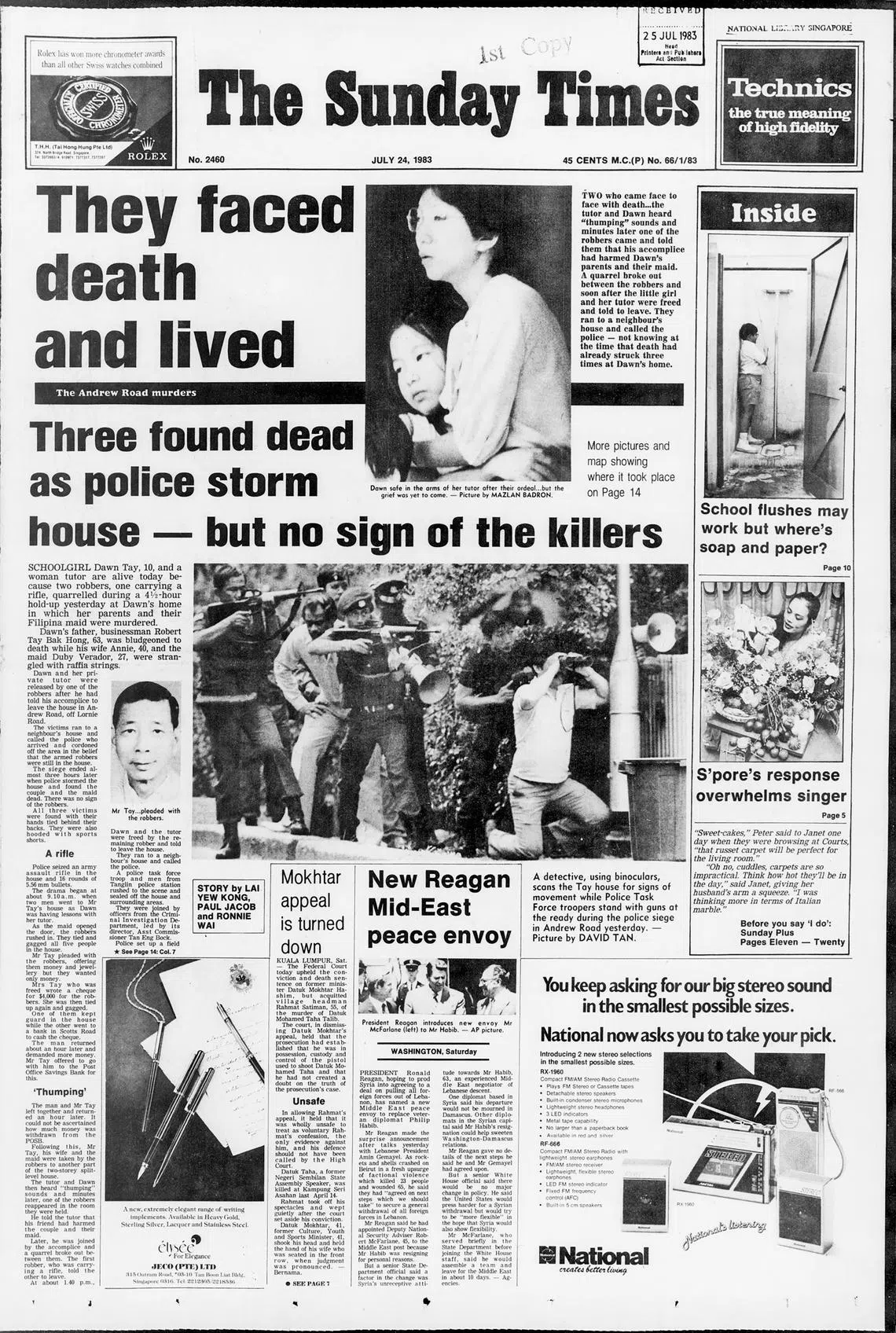

The Andrew Road murders made front-page news on July 24, 1983. A couple and their domestic helper were killed during an armed robbery. The couple’s daughter and her tutor survived after one of the two robbers released them.

PHOTO: ST FILE

On Saturday, July 23, 1983, Madam Tang So Ha was tutoring 10-year-old Dawn Tay on the second floor of the Tay family’s bungalow in Andrew Road. Dawn’s mother, Mrs Annie Tay, sat with them while her father, Mr Robert Tay, and their helper, Ms Jovita Virador, were downstairs.

When Ms Virador answered a knock at the door, two men – one brandishing a knife and the other a rifle – barged in and tied everyone up.

The man with the knife, later identified as Singaporean Sek Kim Wah, 19, had Mrs Tay write a $5,000 cheque and took Mr Tay to withdraw another $7,000 from the bank. The man with the rifle, Malaysian Nyu Kok Meng, also 19, guarded the hostages.

After Sek and Mr Tay returned, the robbers put Mr Tay, Mrs Tay and Ms Virador in separate rooms while they continued ransacking the house. Loud thumps followed. Nyu burst into the room where Madam Tang and Dawn were being held, looking distressed.

Sek had used a raffia string to strangle Mr Tay, then bludgeoned him to death with a wooden stool, before doing the same to Mrs Tay and Ms Virador. Nyu was apparently against this. Eventually, Sek left in Mr Tay’s Mercedes-Benz with the loot.

Singaporean Sek Kim Wah was found guilty on Aug 14, 1985, of the Andrew Road murders. After his appeal was rejected, he was hanged on Dec 9, 1988.

ST PHOTO: FRANCIS ONG

During the trial in July 1985, Madam Tang’s statement on what happened was revealed: She said that Nyu had untied her and Dawn and handed them a map of where his accomplice lived, his own Malaysian identity card and instructions to inform his family he was sorry. He also asked to be buried next to his late best friend, whose name he wrote inside Dawn’s exercise book.

The tutor and Dawn ran to a neighbour’s house to call the police. When police arrived, they cordoned off the area thinking the killers were still inside the house. After nearly three hours, they stormed the building. By then, Nyu had fled to Malaysia after a failed suicide attempt, leaving the rifle and loot behind.

Dubbed the Andrew Road murders, the story written by Lai Yew Kong, Paul Jacob and Ronnie Wai was the lead story in The Sunday Times on July 24, 1983.

Police identified the gunman as Nyu from his identity card. But who was his accomplice? A breakthrough came in end-July. The rifle was found to be a stolen M16 from the Singapore Army. A national serviceman told police he saw Sek carrying two rifles around the time of the theft.

Sek was arrested at his sister’s flat on July 29, 1983. Nyu surrendered three days later and was extradited to Singapore.

The trials drew significant attention. The front page of the July 9, 1985, paper reported that Nyu had been sentenced to life imprisonment and six strokes of the cane for armed robbery. The murder charges against him were withdrawn.

Meanwhile, police found that Sek had also murdered a couple and dumped their bodies at Seletar Reservoir a month before the Andrew Road murders, bringing his victim count to five, and making him one of Singapore’s few serial killers.

Interviews with Sek’s brother shed light on their troubled childhood, marked by neglect and poverty. Sek grew into a resentful teenager, idolising criminals such as Singapore’s most wanted gunman, Lim Ban Lim.

On Aug 14, 1985, Sek was found guilty of the Andrew Road killings. He thanked the High Court judges in Cantonese for sending him to the gallows, saying it would be “thrilling to be hanged”.

More than five years later, after his appeal was rejected, Sek was hanged on Dec 9, 1988.

A murder that shook two nations

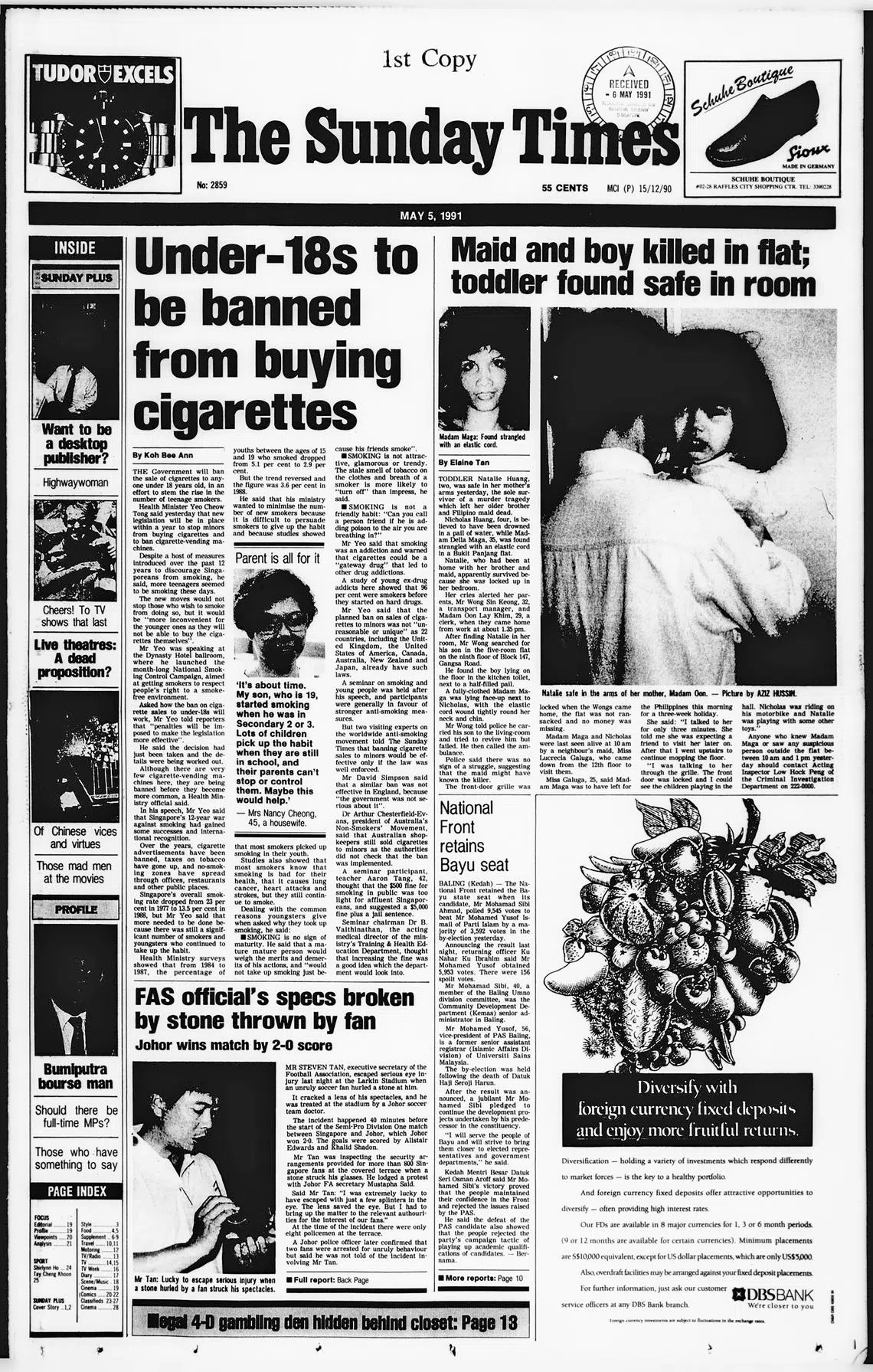

On May 5, 1991, the paper reported that a couple had returned home to find their young son drowned in a pail of water and their helper strangled. Their helper’s friend, Flor Contemplacion, was later charged with the double murder.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The execution of foreign domestic worker Flor Contemplacion in 1995 strained diplomatic ties between Singapore and the Philippines.

On May 5, 1991, The Straits Times reported a shocking tragedy: a couple had returned home to find their four-year-old son, Nicholas Huang, drowned in a pail of water. Their Filipino helper, Madam Della Maga, had been strangled with an elastic cord, and their two-year-old daughter, Natalie, was found locked in a room.

Three days later, the paper reported that Madam Maga’s friend and fellow Filipino domestic helper, Flor Ramos Contemplacion, 38, had been arrested and charged with the double murder.

Subsequent coverage reported that Contemplacion had killed Madam Maga in a fit of anger and drowned Nicholas to prevent him from identifying her as the killer. She spared Natalie, who could not speak yet.

Foreign domestic worker Flor Contemplacion (centre) was hanged on March 17, 1995. She had been convicted of the double murder of a fellow Filipino helper and a four-year-old boy.

PHOTO: SHIN MIN DAILY NEWS FILE

Contemplacion confessed to the murders and was charged. But she later claimed that she had been coerced by Singapore police into confessing. An article on Jan 29, 1993, reported her saying the police had used a picture of the Virgin Mary to force her into confessing. This claim was proven to be false, and Contemplacion was sentenced to death in January 1993.

A year later, appeals were made on her behalf. The Straits Times reported Contemplacion saying that on the day of the murders, a mysterious “voice” had instructed her to visit Madam Maga, who appeared to be “very small and tiny” to her while Nicholas “looked like a small cat”. She asserted that she was suffering from psychiatric issues at the time of the killings, and could not control herself when she committed the murders.

As her execution date neared, the case drew widespread attention in the Philippines, where many believed she was innocent or mentally unwell. Then Philippine President Fidel V. Ramos made two personal appeals to then President Ong Teng Cheong – first for clemency, and then to delay the execution in the light of new claims. The Singapore Government, however, upheld the verdict, stating that the case had been rigorously reviewed through due process.

While Contemplacion was on death row, alternative theories emerged – including one suggesting that Nicholas’ father was the real killer – but these were investigated and dismissed. She was executed on March 17, 1995.

Her death triggered outrage in the Philippines. Thousands of Singapore flags were burned in protest, Singaporean products were boycotted, and then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong’s planned visit to Manila was cancelled. Of the 300 Singaporeans then in the Philippines, about 200 returned home early. Filipinos expressed fury at both the Singapore Government, for refusing to show mercy, and their own government, for not protecting one of their nationals.

The incident also ignited a broader debate about the rights and treatment of migrant workers.

Caelyn Tan interned at The Straits Times from September 2024 to February 2025 while a student at Nanyang Polytechnic. She hopes to return to The Straits Times as a crime reporter after university.