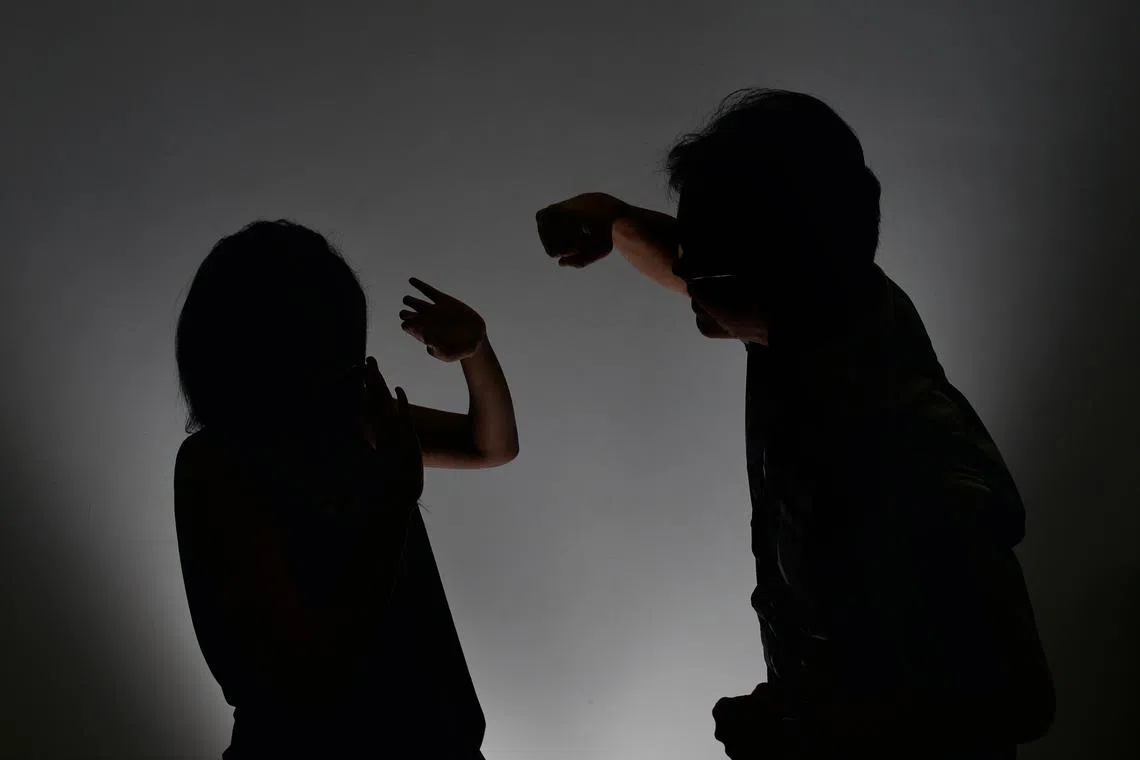

Spousal abuse cases rise in Singapore as more willing to report abusive husband or wife, say social workers

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

In 2023, there were 2,008 new spousal violence cases, up by 15 per cent from 1,741 such cases in 2022.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – The greater willingness to report an abusive husband or wife has led to a steady rise in the number of spousal abuse cases in the past few years, say social workers.

In 2023, there were 2,008 new spousal violence cases, up by 15 per cent from 1,741 such cases in 2022.

In 2021, the figure was 1,632, according to the inaugural Domestic Violence Trends report released by the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) on Sept 26.

An MSF spokeswoman said this is the first time the ministry is releasing data on spousal violence.

Social workers who work with victims of domestic abuse said public education campaigns about family violence by the MSF and other agencies over the years have led to greater awareness of the problem and eased the stigma of seeking help to end the abuse.

Mr Martin Chok, deputy director of family and community services at Care Corner Singapore, said: “In the past, people didn’t want to wash their dirty linen in public.

“But with the Government’s focus on (tackling) family violence, people are more aware, and we get families calling in saying that their relatives have been harmed.”

It is also easy to report the abuse through the National Anti-Violence and Sexual Harassment Helpline launched in 2021,

Ms Lorraine Lim, deputy chief executive of the Singapore Council of Women’s Organisations (SCWO), said: “Domestic violence is a complicated issue as the person causing harm is also the person the victim loves.”

Victims may choose not to report the violence for fear of getting the abuser into trouble with the law, or may worry that making a report would end the relationship, among the myriad reasons why they choose to keep mum about the abuse, she added.

The SCWO runs the Star Shelter for women and children who are survivors of family violence.

Social workers say that most of the abused spouses are the wives.

Victims usually suffer from a mix of various types of abuse, such as physical violence, and emotional and psychological abuse.

Many victims they see endure the abuse for an average of between four and seven years before they seek help, Ms Lim said.

Take for example Anamika (not her real name), 47, who endured emotional and psychological abuse by her then husband for 11 years.

He did not allow her to have a mobile phone, call her family or to go out of the house without his permission. For most of their marriage, he did not allow her to work.

He also installed a CCTV camera in their home to monitor her while he was at work. Anamika said he criticised her constantly and often threatened suicide to get his way.

She said: “I just felt that there was no hope, like I gave up hope of living a normal life. I felt I had no identity, like I didn’t exist.”

She tolerated his coercive behaviour until she decided “enough was enough” and sought help.

She applied for a personal protection order (PPO), which restrains a person from committing violence against a family member, against her former husband.

She has since divorced him, and she now lives with her teenage daughter.

Then, there is Rose (not her real name), whose alcoholic husband physically hit her at times, and inflicted emotional and psychological abuse on her.

The office worker in her 40s said: “He is an alcoholic and when he is drunk, he can’t control his behaviour and emotions.

“And he kept blaming me and threatening to kill me or kill himself when we fought.”

She stayed in the marriage for the sake of her young children, and kept mum about her suffering for fear of being judged or criticised.

She put up with the abuse for three years until the day she felt he had put her life in danger.

She filed for a PPO and divorced him.

The Domestic Violence Trends report covers only spousal violence cases overseen by community agencies, such as protection specialist centres and family service centres.

There are cases not known by community agencies as the victims reported them to the police or applied for a PPO, said the MSF spokeswoman. So, the actual number of spousal abuse cases could be even higher than the figures cited by the report.

The spokeswoman added: “We are keen to put together a holistic picture of the domestic violence situation in Singapore based on data across agencies and stakeholders such as the courts. However, this would take some time.”

Uptick in abused seniors

Meanwhile, slightly more seniors aged 65 and older were abused, said the report. There were 297 new Tier 1 elder abuse cases in 2023, up from 294 in 2022 and 283 in 2021.

The Tier 1 cases are those with low to moderate safety and risk concerns, which are managed by community agencies, while Tier 2 cases are high-risk cases managed by the MSF.

Ms Suriana Mohd Shah, centre director of Trans Safe Centre, said that training social service professionals who work with seniors to spot elder abuse is crucial.

This ensures timely attention to the issue, and cases can be managed by community agencies, she added. This is one possible reason behind the slight uptick in Tier 1 elder abuse cases.

Social workers say many of these seniors were abused by their adult children.

One case Care Corner Singapore has seen was when a woman in her 60s called for help. Working in a blue-collar job, she was supporting her son and husband, who are both unemployed, said Mr Chok.

The son, who is in his 30s, kept threatening to hit or kill his mother if she did not give him money or give in to his other demands.

The last straw for her was when he threw an object at her, hitting and breaking the television.

Mr Chok said: “She was afraid for her life and felt she couldn’t protect herself any more.”

Social workers helped her apply for a PPO against her son, and taught her how to keep herself safe.

But many abused seniors tend to stay silent about abuse, social workers say, as they do not want to get their abusive children into trouble with the law or they are dependent on their children, among other reasons.

Ms Han Yah Yee, acting chief executive of social service agency Montfort Care, said: “I think it’s harder for seniors to seek help as they may feel the shame (of the abuse) more.

“They may also be afraid that they will have no one to send them on their final journey (perform the last rites) if they report their children for the abuse.”

The number of new Tier 2 elderly vulnerable adult cases fell significantly from 84 cases in 2021 to 42 cases in 2023.

An elderly vulnerable adult is a senior aged 65 and above who, because of mental or physical infirmity, disability or incapacity, is incapable of protecting himself or herself from abuse, neglect or self-neglect.

Community, eldercare and healthcare agencies have worked with these vulnerable seniors and their families to address the root causes of the abuse, said the report, which could have prevented the issues from becoming more serious.

If you are or suspect someone is facing family violence, please call the National Anti-Violence and Sexual Harassment Helpline on 1800-777-0000.