Mental health screening scheme at National Healthcare Group polyclinics helps close to 100 teens

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

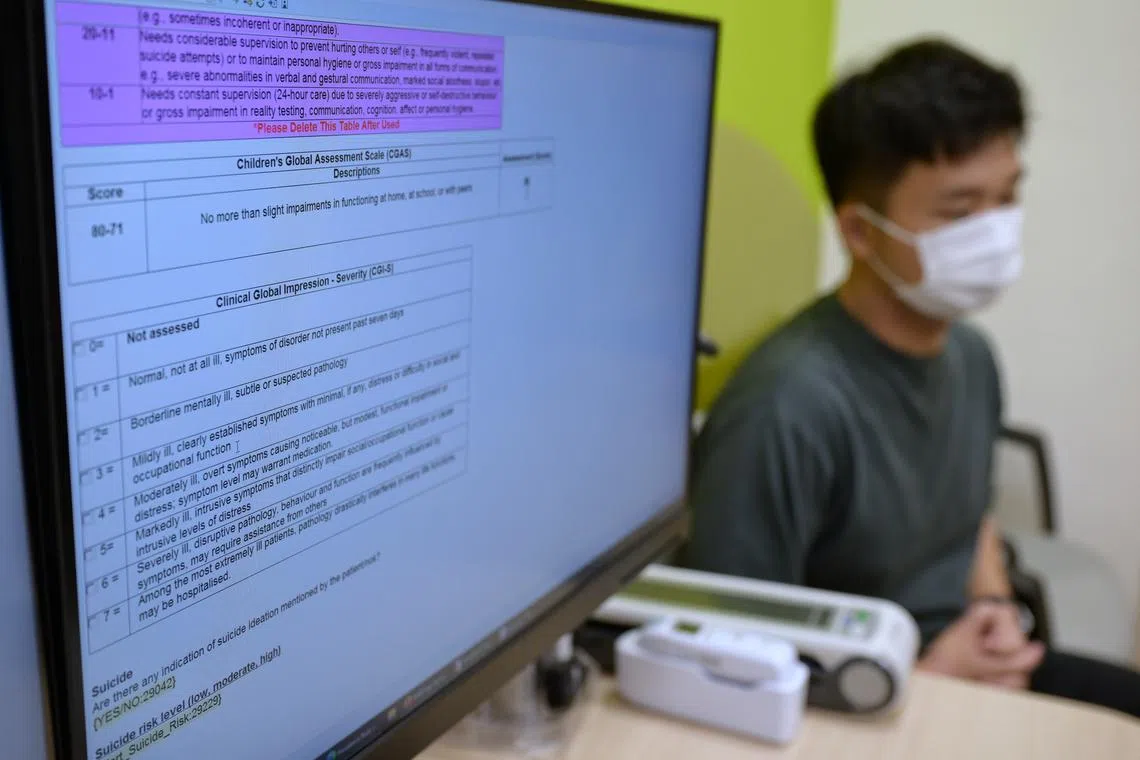

Those who show possible signs of mental health issues are screened during their regular consultations.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

SINGAPORE – Close to 100 young people between the ages of 13 and 17 have benefited from a mental health screening programme rolled out at all nine polyclinics run by the National Healthcare Group (NHG).

The programme, Adolescent Evaluation and Rapid Treatment of Mental Health, or Alert, was piloted at Hougang Polyclinic in November 2021. It has been available across all of NHG’s polyclinics since April 2023.

Those who show possible signs of mental health issues are screened during their regular consultations.

At a briefing held on July 9 at Khatib Polyclinic, Dr Eugene Chua, co-lead for National Healthcare Group Polyclinics’ (NHGP) mental health programme, said that young people undergo many transitions.

Biologically, they are undergoing puberty, which brings about physical and hormonal changes that some can find distressing. Psychosocially, teenagers are developing their personal identities and seeking acceptance from peers and society.

If these stressors are not properly managed, young people can be at risk of mental health issues.

Dr Chua said that some signs of youngsters with mental health problems include those who come to the polyclinic frequently for issues like headaches, chest pain and stomach aches.

Those with recurrent visits would likely be screened under the Alert programme.

“People with anxiety tend to have a lot of muscle tension, and that could cause issues like headaches, shoulder pain or lower back pain. One of the symptoms of anxiety... is the feeling of butterflies in the stomach, which can present as abdominal pain. When you’re worried, anxious or sad, your heart starts to beat a little faster, and that can present as some element of chest tightness,” Dr Chua added.

Another group of young people who are screened are those who suspect they have a mental health condition, such as depression or anxiety.

“We will take the opportunity to find out more about why they think they have such disorders and, more importantly, to identify the symptoms and struggles which they are going through,” said Dr Chua.

Those on the Alert programme will work with family physicians and medical social workers on a personalised care plan over a six-month period. Family physicians will manage the youngster’s biological or acute symptoms, while the medical social workers take care of his emotional well-being via counselling sessions.

During this half-year period, a psychosocial assessment will be conducted to better understand the support structure the youngster has, including family, friends and hobbies. He will then undergo three or four counselling sessions to address his issues and learn how emotions can affect the body.

Beyond the polyclinic, the medical social workers will also work closely with community partners like family service centres or schools.

The six-month programme is free for young people, but they have to pay for their consultation with the doctor, which costs $8.10 per visit.

Upon being assessed that they have made improvements in their condition and are able to manage their stressors, the youngsters can leave the programme. They will be given tips on how to maintain good mental wellness.

Those who need more help could be referred to specialists.

Some indicators that a youngster may need more specialised help would be his inability to sleep due to anxiety for days on end, or his having difficulty leaving the house.

About 10 per cent to 15 per cent of those involved in the programme were referred to specialists, said Dr Chua.

Addressing questions on whether parents would be informed that their child is on the programme, Dr Chua said that if the child indicates that he does not want his parents involved, his preference would be respected.

However, if the patient is in danger and having suicidal thoughts, for example, doctors will work with him on at least informing a trusted adult.

“If youth tell us that they don’t want their parents to know (they are on the programme), it’s an opportunity for us to explore why... Usually, through the counselling process, we identify that some of them have miscommunication and misunderstanding. We will then take the opportunity to see if they are open for us to engage parents,” Dr Chua added.

NHGP chief executive Karen Ng said: “Through this initiative, we provide an upstream avenue that is youth-friendly and non-stigmatising. We hope youth at risk will be more open to seeking help early, get access to resources that empower them to overcome challenges, and alleviate their risk of developing mental health conditions in adulthood.”