Commentary

Megan Khung deserved better. It takes all of us to keep other children like her safe

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Megan Khung died after her mother Foo Li Ping's boyfriend Wong Shi Xiang punched her in the stomach.

PHOTOS: CCXXCXCX/INSTAGRAM, SHIN MIN DAILY NEWS READER, INSTAGRAM

Follow topic:

The death of four-year-old Megan Khung, who suffered horrific abuse at the hands of her mother and her former boyfriend, has shocked many Singaporeans.

Topmost on people’s minds are these questions: Why did Megan have to die? What more could the child protection authorities and social service agencies have done to save the child?

On April 8, the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) gave a timeline of the actions taken by Beyond Social Services (Beyond), which runs the pre-school Megan attended, and the authorities involved in the case.

More than five years after Megan’s tragic death in February 2020,

In its media statement on April 8 and public replies about the case, the MSF flagged what Beyond failed to do – but said less about what it actually did to try to keep Megan safe.

In a statement on the night of April 11, the ministry said it will conduct a further review on the Megan Khung case, which will cover the responses of all parties involved – including Beyond, the Early Childhood Development Agency (ECDA), MSF’s Child Protective Service (CPS) and the police.

Additional information that Beyond had shared with the MSF after the ministry issued its earlier statement will be included, and conclusions will be published after the review is done.

No single organisation can shoulder the burden and responsibility of child protection work alone. It takes a village to keep a child safe from their abusive parents.

Beyond stronger protocols and processes, what is needed is also a shared mindset that we are in this together.

In its April 8 statement, the ministry had said that the report Beyond submitted to the ECDA did not fully describe the severity of her injuries,

The MSF also noted that Beyond did not escalate the case to the MSF’s CPS, which manages high-risk child abuse cases and which has the statutory powers to remove children from their families to keep the children safe.

To be fair, Beyond made multiple efforts to protect Megan when it suspected abuse.

For example, the agency drew up a plan to keep Megan safe – moving her out of her mother’s house to temporarily live under the care of her grandmother.

Beyond also consulted a child protection specialist centre, which manages child abuse cases of low to moderate risk, after Megan’s mother took her home to live with her, withdrew her from the pre-school and became uncontactable.

It also went again to ECDA, the regulatory authority for pre-schools, to ask if the girl was enrolled in another pre-school.

Social workers familiar with child protection work say that the Beyond staff had done their part by consulting a child protection specialist centre.

These centres would have alerted the CPS to the case if they deemed it serious enough based on the information they had, such as the recency, frequency and severity of abuse.

It is important to point out that with the benefit of hindsight, especially after a court case where a host of details are laid bare, one can see a fuller picture.

But at that point, Beyond and the other agencies would have been dealing with limited, incomplete and even inaccurate information based on their interactions with Megan’s family, when events were unfolding in real time.

And these professionals would have to make assessments and decisions based on the information they had back then.

What adds to the challenge of managing such cases is that the nature of abusive behaviours is volatile and unpredictable, and situations can change quickly in a matter of hours or days.

Mr Martin Chok, deputy director of family and community services at Care Corner Singapore, said there can be a sudden escalation in the severity of abuse after periods of peace and calm.

He added: “Some caregivers deny us access to the child, or they hide the truth.”

Collective effort needed to tackle abuse

On Feb 21, 2020, the mother’s former boyfriend punched Megan in her abdomen and she died after months of senseless violence. The couple burned her body on May 8, 2020, to hide their crime.

On April 3, Megan’s mother, Foo Li Ping, 29, was sentenced to 19 years’ jail.

When things go wrong, as members of the public, we all can play a part by resisting the tendency to bay for blood.

It is critical to give the authorities time and space to find out what went wrong, how processes and protocols can be remedied or improved, and how agencies and their staff can be better equipped to do their work.

In reality, no organisation can go the distance alone in child protection work. It needs to be the collective work of agencies, with their respective expertise, competencies and resources, to look out for and help the vulnerable and their families.

To save children, social service professionals have to work with and help their family members too. And these include perpetrators of the abuse.

Mr Chok said: “Child protection work is not short-term intervention. It requires long-term support and working with different partners to keep the child safe and to build up the caregiver’s ability to manage their stressors and to solve problems.”

In Megan’s case, it would also be instructive if the MSF gave a more detailed account of the roles and responses given by the agencies involved.

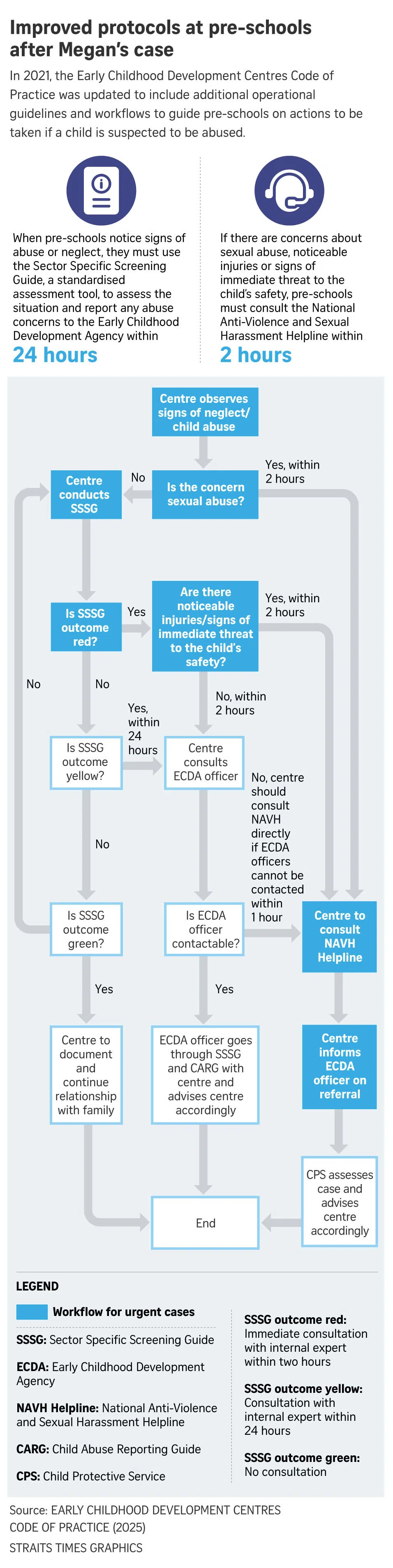

To be clear, protocols on how pre-schools should handle suspected abuse cases were enhanced after Megan’s death. In 2021, new operational guidelines and workflows specifying the actions to take if pre-schools suspect a child is abused were included in a code of practice for pre-schools.

For example, if there are concerns about sexual abuse, noticeable injuries or signs of immediate threat to the child’s safety, pre-schools are required to consult the National Anti-Violence and Sexual Harassment Helpline within two hours.

If a child with abuse concerns has been regularly absent or is withdrawn from pre-school without valid reasons, pre-schools are required to inform the social worker or MSF’s child protection officer working with the child. This was not required before 2021.

If the child is not known to any social service agency or CPS, pre-schools must report the matter to ECDA, which will then assess whether a report to CPS is necessary, said MSF.

The ministry has also reviewed and tightened the operating processes between ECDA and CPS.

The MSF has repeatedly said that tackling domestic abuse has to be a whole-of-society effort, as such violence happens behind closed doors and the secrecy surrounding abuse makes it hard to detect or prevent. It takes all eyes and ears – from neighbours, colleagues and teachers, to social service professionals and healthcare workers – to spot and report the abuse.

The number of child abuse cases each year is significant.

In 2023, there were 2,787 new child abuse cases with low to moderate safety and risk concerns and another 2,011 new high risk cases.

And these are just new cases, not counting existing ones.

So Singapore needs all hands on deck to keep these thousands of children safe from their violent loved ones.

Social service professionals and agencies need to know and feel they will be supported if things go south – despite the best of intentions and efforts.

It bears highlighting that there is no fool-proof child protection system anywhere in the world. Beyond processes and protocols, it is important to nurture this “we are in this together” mindset in tackling abuse. Such an attitude would make all the difference.

Then it no longer becomes just my job, or your job; my responsibility or your responsibility. It becomes our collective duty – and our shared humanity – to keep the other Megans out there safe.

Theresa Tan is senior social affairs correspondent at The Straits Times. She covers issues that affect families, youth and vulnerable groups.