CAN WE DO WITHOUT MAIDS?

Maids: Essential, or a luxury?

From a wealthy family's substitute parent figure to the working couple's indispensable home help, Insight looks at the changing role of the domestic helper.

When Indonesia said last month that it intended to stop sending new live-in maids abroad from as early as next year, alarm bells sounded for some employment agents and families in Singapore.

Indonesia, after all, is the biggest source of domestic helpers, with more than 125,000 women here.

And over the years, maids have become integral to the smooth running of many Singaporean households. They pick up after the children, fetch them from school, accompany their elderly charges to the hospital and keep homes tidy, among their many roles.

For adults who work irregular hours, the maids' presence at home is a special boon. And, of course, they are relatively more affordable to employ than getting specialised home and eldercare services.

A spokesman for maid agency Express Maid says: "The salary of our helpers starts from $500 a month. It's slightly higher than a once-a-week cleaning package, but a live-in helper can do many other things, like take care of young children."

But others say that the Indonesian proposal has some merit, as they see some Singaporeans becoming a pampered lot.

"There are some who really need maids, especially those with sick, aged parents. But for the rest, it's possible to do without them if you adjust expectations about neatness and work a little harder, like waking up early to make breakfast for the family," says pastor Andy Goh, 40, a father of three.

The very nature of the relationship between maids and employers also has consequences. This includes how families and other Singaporeans - who interact with maids in homes, at neighbourhood centres and parks, and on public transport - view and regard the countries which domestic helpers come from. Countries that Singapore sources its maids from include the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, as well as Indonesia.

And the attitude of Singaporeans towards these foreign nationals - including how such attitudes are perceived in the foreign capitals - can impact on policies.

Myanmar, which has about 30,000 maids here, has over the past two years imposed bans preventing its women from working as maids here and in Hong Kong, citing ill-treatment and abuse. The Philippines in the past has also banned citizens from being maids overseas, as has Indonesia.

Another factor in the maid equation here is households having to adjust to having a non-family member in the home - with needs to be addressed.

How did Singapore grow so reliant on maids? And can Singaporeans do without them?

FROM AMAHS TO MAIDS

From the 1930s to 1960s, employing live-in help was the domain of expatriates and wealthy local employers. This was the time of the legendary amahs, women hailing mostly from Guangdong province in China and distinctive due to their plaited hair and "uniforms" comprising white blouses and black pants.

Regarded as part of the family, they were figures of respect. Most families gave their amahs the leeway to discipline the children, allowing them to function as another "parent".

But when Singapore industrialised from the late 1960s, more Singaporean women took up jobs in factories and offices, sparking a need for paid domestic help to look after the home.

So the Government introduced the Foreign Domestic Servant Scheme in 1978, enabling women from neighbouring countries, including the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Thailand, to be employed as paid domestic help.

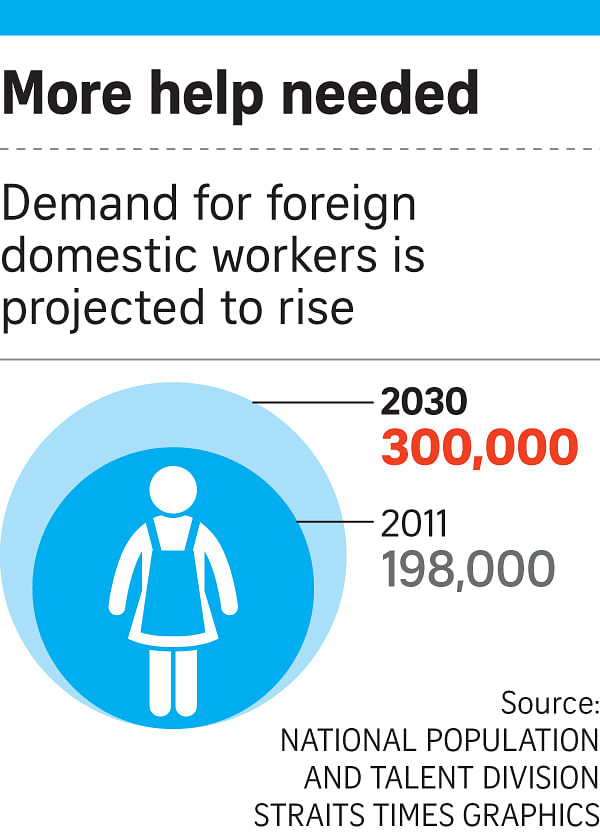

From a base of about 5,000 in the late 1970s, the number has grown, and there are about 227,100 foreign domestic workers here today.

The labour force participation rate of married Singaporean women comprising citizens and permanent residents, meanwhile, has increased from 14.7 per cent in 1970 to 63.2 per cent last year.

Unlike the much-loved amahs, maids today are treated by many families as an employee who happens to live in their home, say representatives of migrant workers' groups.

In extreme situations, some employers even install Web cameras to keep an eye on them, as is the case for a 33-year-old maid from Batia in the Philippines who wishes to be known only as Niva.

"I work from 6am to 11pm. I don't eat meals on time and there are cameras everywhere except in the toilet. There isn't enough freedom," she says.

The skills required of a maid are also higher today. Some are expected to help children with ever-demanding homework and to have the computer skills to assist them; care for the elderly, which has become more complex in terms of nursing skills; and run the home, which involves operating sophisticated appliances and being able to cook according to dietary demands.

And Singaporeans get all these comparatively cheaply. The services of a live-in Indonesian maid start from $815, taking into account her salary and the monthly $265 levy, but excluding costs of insurance, food and medical care. There are levy concessions for families with young children and elderly parents.

In contrast, a bundle of specialised services - for homecooked catered meals, weekly cleaning and caregiving for the elderly or children - could easily add up to more than $2,000 a month.

Yet, vestiges of the notion of maids having a role in the family beyond that of a mere labourer continue. For example, maids do not come under the Employment Act, as the engagement of domestic labour is considered a private contract between the maid and the employer.

Furthermore, under the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act, foreign domestic workers must live with their employers at the addresses stated on their work permits.

A WAKE-UP CALL FOR SINGAPOREANS?

However, into this existing situation come the Indonesian authorities, who want their domestic workers to live separately from their employers in dormitories, work regular hours and get public holidays and days off.

The move is part of Indonesian President Joko Widodo's plan to professionalise informal employment.

However, having domestic helpers live away from home poses logistical and financial challenges. Some worry that this defeats the purpose of hiring someone to provide ready care for aged parents or children. Others wonder if they would have to pay for accommodation and transport to and from their homes.

Some welcome the proposals, saying that Singaporeans are pampered and it is high time they learnt to cope independently.

Reader Jason Charles Ingham, in a letter to The Straits Times' Forum page last week, noted that Singaporeans seem to be delegating the care of their children and parents to domestic helpers. "When our children cry in the middle of the night, should we, the parents, not be the ones who go to comfort them? How can we reasonably expect an employee to care for our offspring?" he asked.

Domestic helper Sheila Paspe, 29, who left the Philippines four years ago, also thinks some Singaporeans may have become overdependent: "Friends say employers can be lazy, like asking them to turn on a light in another room before they walk in," she says.

Then there are others who are concerned about possible problems that could arise from how Singaporeans treat fellow South-east Asians who work in their homes, doing jobs that some will perceive as menial tasks.

There is also concern about the potential effect that the attitude and behaviour of parents and grandparents towards maids can have on the young. Are there those who grow up thinking that Singaporeans are superior to others from the region, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) ask.

How parents talk about the role of the helper makes all the difference, says National University of Singapore sociologist Paulin Straughan. "A lot of parents are really negligent about that. Their own prejudices flow through, which become a generalised prejudice towards people of certain countries."

Ms Flora Sha, who manages maid agency United Channel, puts it more bluntly: "We remind our clients that maids need space to destress. We can do more to change our reputation of Singapore being a modern slave trader."

Then again, the situation is not helped by policies like the $5,000 security bond imposed by the Ministry of Manpower, says Mr Jolovan Wham, executive director of migrant workers group Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics. "The bond makes you feel responsible for the workers, and so there's this sense of 'ownership', not just over their labour, but also their bodies, whereabouts and who they socialise with," he says.

Some employers speak harshly to their maids or restrict freedoms, like confiscating their phones. Others treat maids as invisible strangers, neither to be seen nor heard by the rest of the family, say NGOs.

The maids' common complaints are about long hours, not having time off and being overworked, they add.

Several maid agents said that when mandatory days off - or payment in lieu of days off - were increased from monthly to weekly in 2013, many employers worried they could not cope.

Others feared the extra time would lead to their maids coming under the influence of the wrong crowd while out and about.

One way to improve attitudes is to recognise the skills that good domestic workers bring to the table, and compensate them accordingly, says Ms Yorelle Kalika, chief executive of Active Global Specialised Caregivers, an agency that brings in foreign home nurses. "The source countries are trying to professionalise their workforce. (They) may be more expensive than a normal maid, but it is win-win: You are getting a professional," she says.

Over at the recently launched Centre for Domestic Employees, which is run by the National Trades Union Congress, its chairman Yeo Guat Kwang says it is working on a clearer fee structure, so Singaporean employers and maids will not be saddled with high recruitment fees, and on qualifications so higher-skilled maids get better compensation.

But Mr Yeo does not think Singapore can go without maids just yet.

"As a unionist, I am happy to see more women joining the workforce. And if it's because of that that we need to get domestic helpers, then my job is to make sure that the employment arrangement is more transparent, and the skill set is one we can trust," he says.

For many couples sandwiched between taking care of young children and elderly parents, having a maid is a necessity, especially when alternatives are in short supply.

Dr Lily Neo, an MP for Jalan Besar GRC, says: "We don't have enough retirement homes, and we can't make family members give up their jobs to take care of their parents. The elderly person falls or has a stroke - having a maid could make the difference between life and death."

It will be difficult to become an entirely maid-less society.

Certainly, Singapore can take steps to having fewer maids, using technology and outsourcing (see other stories). And this will be yet a further step away from the commanding, devoted amah who was part of the family.

• Additional reporting by Royanne Ng

ALSO READ

The household: Cleaners, catering can help

10 years on, helper is very much part of family

Join ST's WhatsApp Channel and get the latest news and must-reads.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on June 05, 2016, with the headline Maids: Essential, or a luxury?. Subscribe