Lunch With Sumiko: Paralympic swimmer Yip Pin Xiu's 'pretty happy the way I am'

Paralympic swimmer Yip Pin Xiu's positive outlook is both inspiring and infectious.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Swimmer Yip Pin Xiu, seen here at Cafe Melba, travels independently, taking taxis or Uber or Grab. She notes that attitudes towards the disabled here have improved in the last few years.

ST PHOTO: KEVIN LIM

Follow topic:

"In my dreams, I still walk," says Yip Pin Xiu.

I feel a twinge when she says this. But pity is not what she wants. It is something she has never wanted.

I'm having lunch with Yip - winner of four Paralympic medals for swimming, including three golds - and she is bowling me over with her happy vibes.

She laughs a lot - a hiccuppy sound that also makes me want to laugh along - is cheerful and chatty and has a very pleasant manner.

When I apologise for the mess I'm making of my sandwich, she giggles and says: "It's okay, I'm not looking at it."

And when I share that I learnt to swim only in my 30s, she says reassuringly: "But at least you did."

She's fine talking about her condition because "it's good for people to know about it".

Yip, 25, has Charcot Marie Tooth, an inherited disorder that causes nerve damage and leads to progressive weakening of muscles. She is unable to walk and uses a wheelchair.

She was born healthy but when she was two, she felt sharp pains and had a foot drop. "You know, when you walk, you can flex your foot up and take the next step. But mine was just like piak piak piak piak piak... I had no flexion or extension of my ankles."

She had an operation but it didn't help. Doctors diagnosed her with muscular dystrophy, more specifically Charcot Marie Tooth.

When she was five, her hands started being affected. She had to stop learning the piano later, but didn't mind as she didn't enjoy it.

She went through primary school wearing ankle-foot braces to help her walk. By the time she entered secondary school, she had to use a wheelchair.

Was it difficult when you realised you had to rely on a wheelchair, I wonder.

"I was happy," she interjects before I finish the question.

Really, I ask?

She nods. "Because walking was starting to get difficult. I couldn't catch up with my friends, I didn't really want to go anywhere, I didn't want to be embarrassed, I didn't want them to wait for me," she says.

"Once I got the wheelchair, I could have more independence in my life. I could start to go around on my own. Maybe not at the start, but eventually."

She did go through a period during primary school when she felt down. "But I think I am generally not a negative person," she says. "So I didn't really harp on it for a very long time. Maybe less than a month."

She can move her legs but they can't bear her weight any more. "In the water, I can still walk," she adds.

Are there things you wish you could do, I venture.

"Dance," she says at once.

"And walking around in high heels."

You could still wear high heels though, I suggest.

"Ya, but then it's different," she says, laughing. "No lah, it's really the smallest things. It's not like I wish I could walk, as in I do but it's fine that I cannot. I'm actually pretty happy with the way I am."

Do you remember walking, I ask, which is when she says she still walks in her dreams. "Really," she continues, breaking into another of her gurgly laughs. "Sometimes."

LAST month, Yip added another accolade to her name - author.

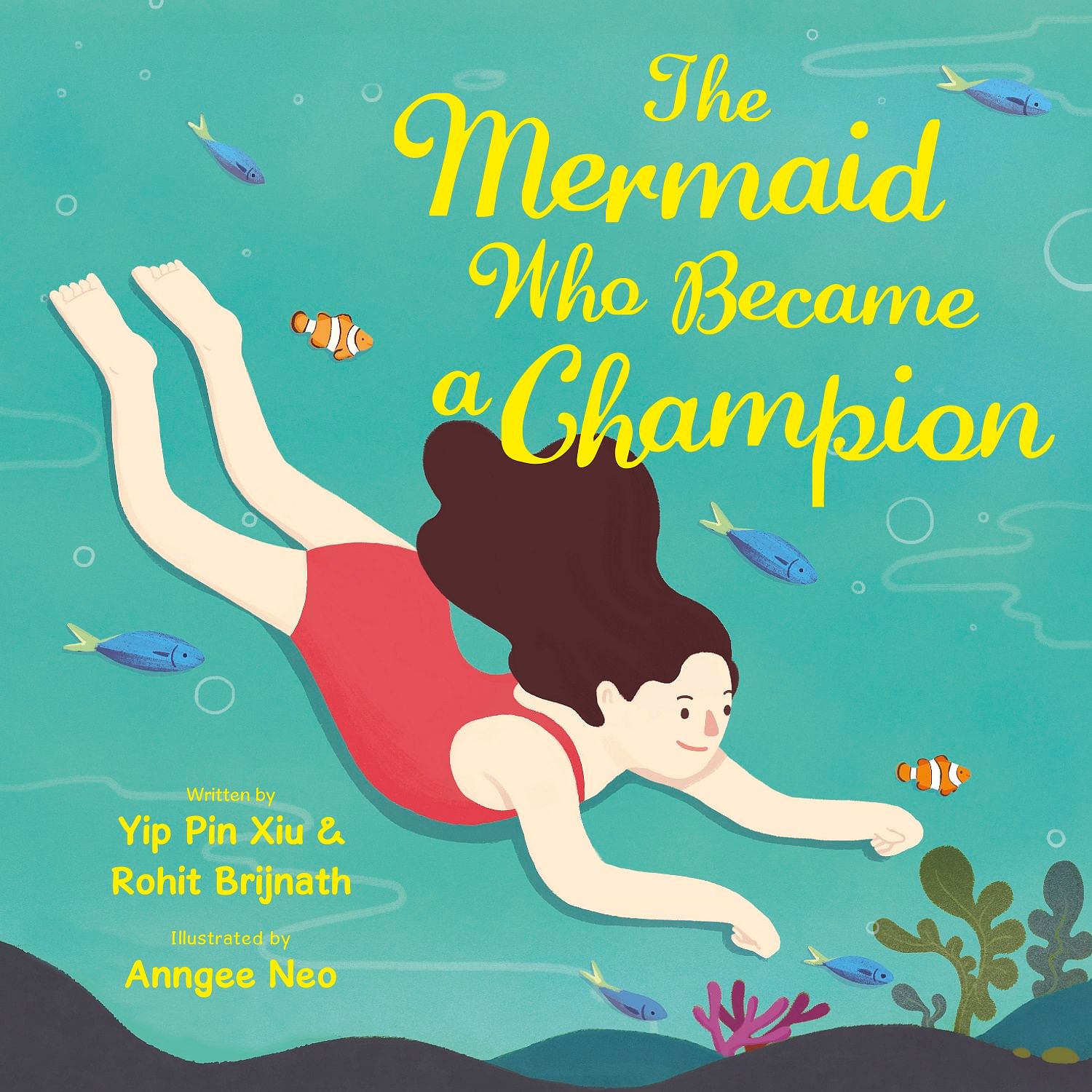

The Mermaid Who Became A Champion, published by Straits Times Press, tells her remarkable Paralympic journey. The 36-page children's book was written by Yip and Straits Times sports columnist Rohit Brijnath and illustrated by Anngee Neo.

At the 2008 Beijing Games, Yip, then 16, made history by winning Singapore's first Paralympic gold medal, as well as a silver. She took part in London 2012 but didn't win, but in Rio last year, came back with two golds in the 100m backstroke and 50m freestyle.

She met Mr Brijnath over four to five sessions to discuss what would go into the book. It marries a fantasy angle - the mermaid theme - with her real life as an athlete.

She took a break after Rio to focus on her studies and graduated with a social sciences degree from Singapore Management University last month. She's now preparing for the Asean Para Games in Kuala Lumpur in the middle of this month, after which she goes to Mexico City for the World Para Swimming Championships.

She's chosen to have lunch at Cafe Melba in Goodman Arts Centre because it's near the Sports Hub where she's meeting her dietitian later. She orders a beef lasagne and I get a chicken and avocado sandwich. "Healthy," she remarks of my choice. "My dietitian would be proud of you."

She has been to the cafe before and so knew it was wheelchair-friendly. Before she goes anywhere new to her, she checks it out on Google Street View "to see if there are like 20 steps".

She travels independently, taking taxis or Uber or Grab. Private car hire drivers tend to be friendlier and more helpful, she observes. But attitudes towards the disabled in Singapore have improved in the last few years. "When I was younger, the environment was less friendly. Now, everybody is very helpful."

I ask if there's been a recent situation that frustrated her. She thinks long and hard.

"Frustrated... noooo, because I don't easily get frustrated at situations," she says finally.

"Sometimes I get frustrated at people, but not situations because I feel if a situation is not something I can control, there's no point getting frustrated about it. It's just making myself angry and I generally try to handle things quite calmly."

Helpfully, she takes another stab at answering my question.

"Sometimes I am in a taxi and drivers who don't know me will tell me, 'Oh, I'm so sorry about what happened to you'. I'm like, 'No, don't worry, uncle, I'm pretty happy the way I am'. But that's not frustrating lah. I cannot remember the last thing that frustrated me, but I'm sure there is something."

She attributes her independence to her father Yip Chee Khiong, who's retired, and mother Margaret Chong, a senior officer at Singapore Airlines. Both are 62.

They didn't treat her differently from her two brothers, Alvin, who's 32 and working in finance, and Augustus, 30, an engineer.

"They let me be who they think I can be," she says. "There are some families where, because you are disabled, you are not allowed to do a lot of things. That will make people think even more about their disabilities and blame themselves for it... In my head, I don't define myself as a person with disability."

The close-knit family was quite sporty, with her mother taking part in marathons and her father doing walking and taiji. She learnt to swim when she was six and remembers the day vividly.

She was at Geylang Bahru Swimming Complex and wearing a denim dress with a bear patch and bear buttons. Her two brothers were being coached and she wanted to go into the water, too. She told her mother, who asked the boys' coach if she could swim.

"The coach had experience with a swimmer with above-knee amputation, so she knew that it was possible."

Yip went into the pool even though she didn't have a swimming costume with her. "I must have taken my dress off and went down in nothing."

She loved being in the water because she could do everything others could do on land. She was also very fast.

When she was about 11, she was spotted by a volunteer from the Singapore Disability Sports Council who invited her to take part in the national junior competition. Giddy with excitement, she signed up for six events and won them all.

Swimming made up for the difficult time she had at Ai Tong Primary where she was bullied by the other children. She had staples stuck in her hair and once, when she stood up from a chair, discovered that someone had sprinkled eraser dust on the seat.

"I just pushed the chair back in and walked off," she says. "I've learnt that the way to not give these people power is to not acknowledge that you're feeling anything they want you to feel."

But she adds of those years: "It didn't scar me or anything because I generally don't really remember a lot of negative episodes in my life."

Bendemeer Secondary provided a more supportive environment and, by then, she was using a wheelchair and could move around.

She was also swimming competitively and had met swimmer Theresa Goh. They became buddies after bunking together at a competition. Goh, 30, has spina bifida and is also a Paralympic medallist.

A Sports Excellence Scholarship from Sport Singapore allows Yip to be a full-time athlete now. Four times a week, she gets up at 4.30am and takes a taxi to Farrer Park Swimming Complex where she trains under former national swimmer Ang Peng Siong. There is also evening training, and on other days she has gym work.

She loves racing even though she still finds it nerve-racking. She gives an entertaining account of her pre-race preparation, including what it's like putting on super-tight competitive swimsuits and wearing a cap that's so tight "it feels like my brains are getting sucked out".

When I point out that she already has three Paralympic golds, she shoots back: "But you don't tell Michael Phelps that, oh, you've gotten gold, you don't want to go again, right?"

She sees herself swimming at least three more years and has mixed feelings about retirement.

While she looks forward to not having to wake up at 4.30am - "I really don't understand why swimmers have to train so early" - she will miss racing. She believes she will still be involved in sports.

Her condition, she says, has stabilised. She doesn't feel pain - "the only pain I feel is muscle aches from swimming" - and says that over the years, her condition has become something she doesn't worry too much about. "There's really no point in worrying. I just want to live my life to the fullest and I know exercise does help to slow it down."

I broach the topic of relationships and ask if it's something she talks about. "If you ask me, I will talk about it," she replies cheerfully.

She has had relationships but is currently single. She acknowledges her disability is an issue "to a certain extent". "I'd like to think no, but I'm sure there are some people who really cannot accept dating somebody with disability and that's just them lah." She hopes to get married and have a family one day, but for now is enjoying being an aunt to her brother Alvin's young son.

We decide to skip dessert and move on to do the video and photos. She is happy to see photographer Kevin Lim because they had worked together on a photo essay before the London Paralympics, and accepts his offer of a lift to the Sports Hub.

She says a cheery goodbye, wheels herself to his car, gets in the front passenger seat and guides him on how to pack her wheelchair.

As I watch them drive off, I am reminded of these fitting lines from her book:

Physically and mentally, for me sport has been great.

It helped me fight my disability and has opened debate.

People now look at us and don't merely see the disabled,

but talent and ambition and someone who is able.

I do not want your pity, I just want respect for my tribe.

There's nothing we can't do, if we work side by side.

- Follow Sumiko Tan on Twitter

- The Mermaid Who Became A Champion is available at major bookstores for $16.

What we ate

Cafe Melba, 90 Goodman Road Goodman Arts, Centre Block N #01-56

1 lasagne: $21

1 chicken avocado sandwich: $24

1 lemonade: $8

1 apple-carrot juice: $9

Total (with tax): $72.97