Light in dark times: Helping to fight fear and misinformation at every health crisis

From outbreaks to epidemics, the paper has helped fight fear and misinformation through the ages.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Mr Paddy Chew, the first Singaporean to publicly announce that he had Aids, at the International Aids Candlelight Memorial and Mobilisation at Bras Basah Park on May 16, 1999. He died on Aug 21, 1999.

TNP PHOTO: KENNETH KOH

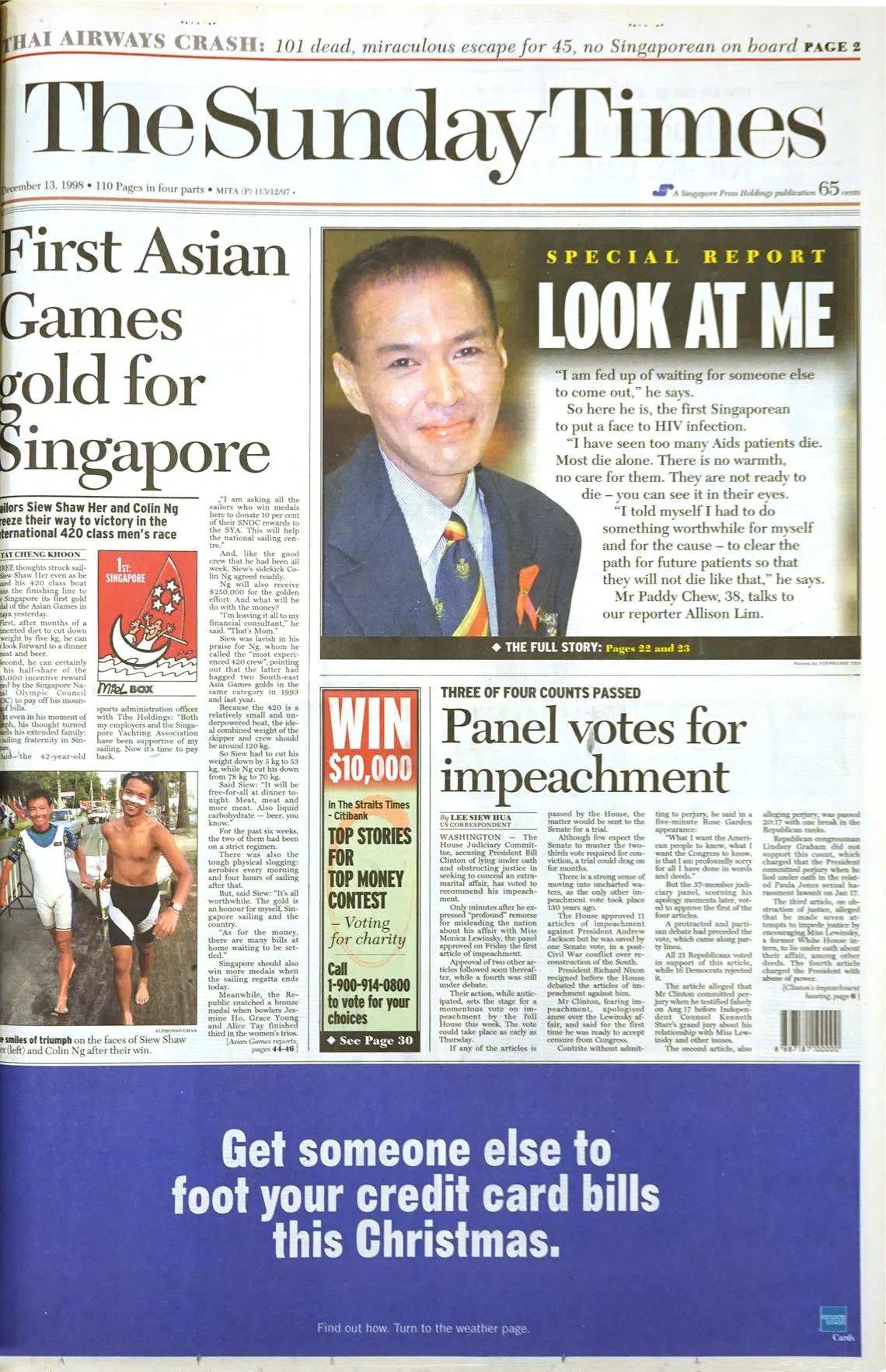

SINGAPORE - On Dec 12, 1998, Mr Paddy Chew became the first Singaporean to publicly announce that he had Aids. The moment was so ground-breaking that The Sunday Times reported it on its front page.

By then, the Aids epidemic had been devastating communities around the world for nearly two decades. A diagnosis of HIV – human immunodeficiency virus – was considered a death sentence as there was no known cure.

People, terrified of being infected, shunned any place or person that had anything to do with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, including healthcare workers.

Mr Chew’s decision to go public, in a 15-minute speech to 400 people at Singapore’s first Aids Conference held at Suntec City, was nothing short of courageous.

The next day, The Straits Times’ Sunday edition carried a photo of Mr Chew, then 38, on Page 1, with more stories on him and the disease across two pages inside.

The photo was taken by photographer Stephanie Yeow, who is now the paper’s deputy head of visualisation. The headline read: “Look at me”. The story of Mr Chew was written by reporter Allison Lim.

A few days later, news editor Alan John penned a column headlined “Let’s start facing Aids and stop fearing its victims”.

On Dec 13, 1998, The Sunday Times carried a photo of Mr Paddy Chew, the first Singaporean to publicly announce that he had Aids, on Page 1.

PHOTO: ST FILE

“At that time, I felt there was so much to say that wasn’t being said,” says Mr John, 71, who retired as the paper’s deputy editor in 2015.

He took an interest in stories about HIV/Aids after becoming a volunteer at the Communicable Disease Centre (CDC) at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, where Aids patients were treated. He was also helping out at the anonymous testing clinic run by non-governmental organisation Action for Aids.

“If you went to the CDC at the time, you saw right away that this was not about the gay community only,” says Mr John.

“The lack of access to life-extending drugs, which were available in Bangkok but not here, was shocking, as was the way family members kept away, and adult children were angry and estranged from fathers who had infected their mothers.”

That The Straits Times chose to prominently feature Mr Chew’s story, and others about HIV/Aids, showed that senior editors were supportive, he says. “I don’t recall any of my bosses ever saying ‘Don’t do those stories’.”

Mr Chew went public about being an Aids sufferer at Singapore’s first Aids Conference, held at Suntec City.

ST PHOTO: STEPHANIE YEOW

Many years later, people working in the area of Aids would sometimes tell him that the paper’s coverage had been helpful in raising awareness and prodding change, says Mr John, who is now a journalism instructor at the SPH Media Academy and a writer of children’s picture books.

Among those who wrote on Aids was journalist Wong Kim Hoh, now the paper’s features editor. His pieces, such as “Don’t shun the HIV positive” in November 2008, and “Fighting Aids openly as a society” in December 2013, made an impact.

Mr Chew died on Aug 21, 1999, and his legacy left an indelible mark on Singapore’s awareness of Aids and public health stigma.

‘Spanish’ flu

On July 3, 1918, as a mysterious virus started sweeping the world, The Straits Times reported that Singapore was experiencing an unusually widespread outbreak of what appeared to be influenza and dengue never seen before “in the memory of the oldest resident”.

On July 3, 1918, an article in The Straits Times noted that postal services were disrupted as postal workers were falling sick amid the “Spanish” flu outbreak.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Headlined “Illness in Singapore, wave of sickness affecting business”, the article noted that postal services were disrupted as postal workers were falling sick.

A follow-up report on Oct 15, headlined “Spanish ‘flu’”, warned that the disease had become prevalent and deadly in Singapore and was spread by coughing and spitting. It urged anyone who came down with it to notify the municipal health officer so their premises could be disinfected.

By Oct 22, schools were ordered to close for a week as cases rose. The situation was dire in other parts of the region. Penang set up a relief fund and more than 300 deaths were reported in a kampung in Seremban.

The 1918 outbreak that hit the world, then in the throes of a global war, was caused by an H1N1 virus with avian origins. Despite the name, it is not believed to have originated from Spain. Neutral during World War I, Spain openly reported on the flu, unlike other nations at war that suppressed such news, giving the impression that it was the epicentre.

The pandemic lasted until 1920 and killed an estimated 50 million people or more worldwide. Unusually, it was especially lethal to young, healthy adults. Older people appeared to have had some immunity from prior flu exposures. In Singapore, 844 official influenza deaths were recorded, though actual influenza deaths were estimated at 3,500.

1957 Asian flu pandemic

In the decades after the Spanish flu, The Straits Times continued to keep readers informed of health issues.

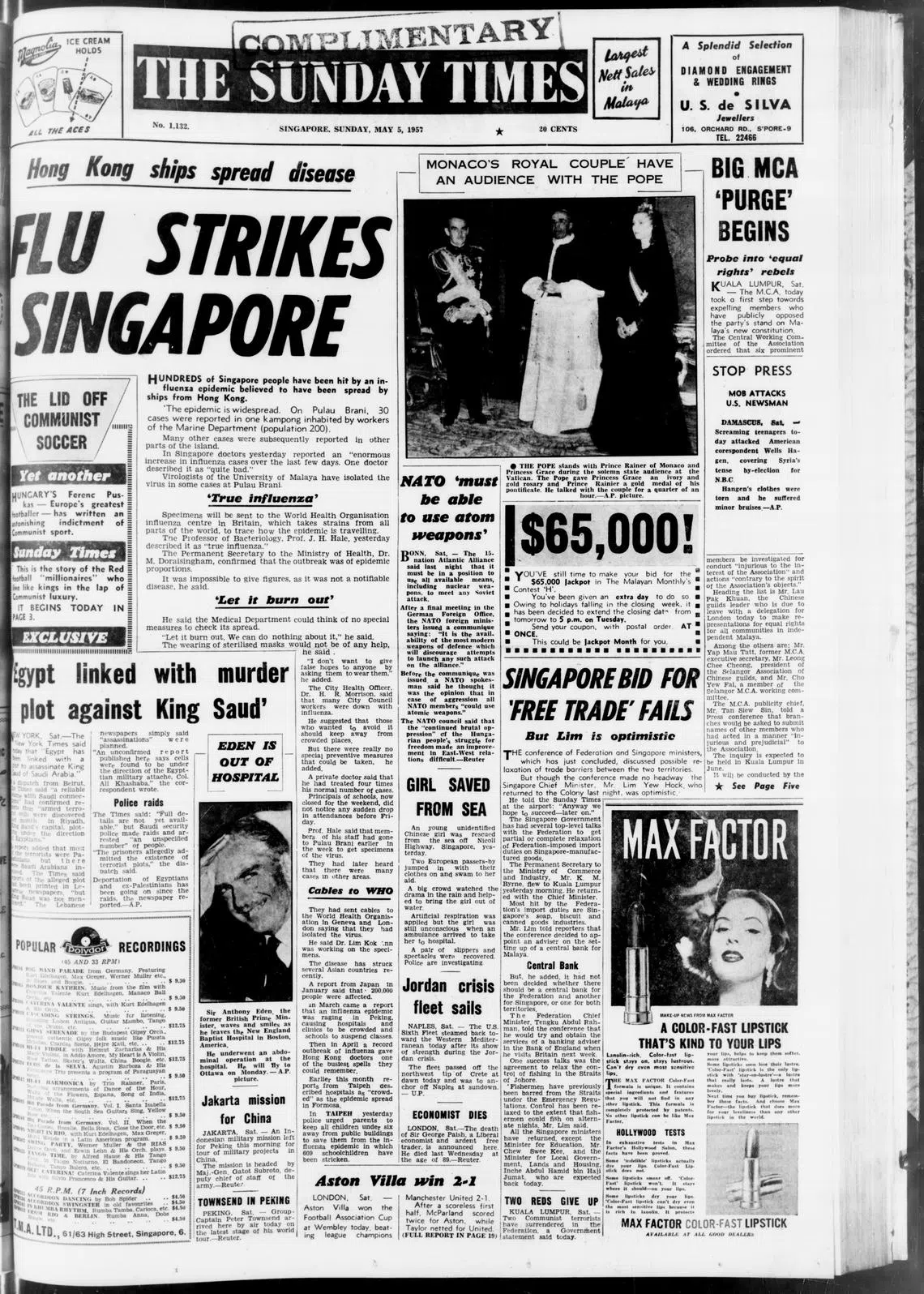

Its coverage of the 1957 Asian flu outbreak echoes familiar scenes when the Covid-19 pandemic hit more than 60 years later.

The 1957 pandemic was caused by a new strain of the influenza A (H2N2) virus. The outbreak began in Guizhou, China, quickly spreading to Hong Kong and Singapore and reaching the US and Europe before the end of the year. It is estimated to have caused more than one million deaths worldwide.

By May 5, 1957, with hundreds in Singapore falling ill, the paper ran the front-page headline “Flu strikes Singapore”.

On May 5, 1957, with hundreds in Singapore falling ill amid the Asian flu pandemic, the paper ran a front-page article headlined “Flu strikes Singapore”.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Health officials acknowledged an epidemic but said precise figures were unavailable as influenza was not a notifiable disease. As there were no specific preventive measures deemed helpful then, the official strategy would be to “let it burn out”. People were advised to avoid crowds.

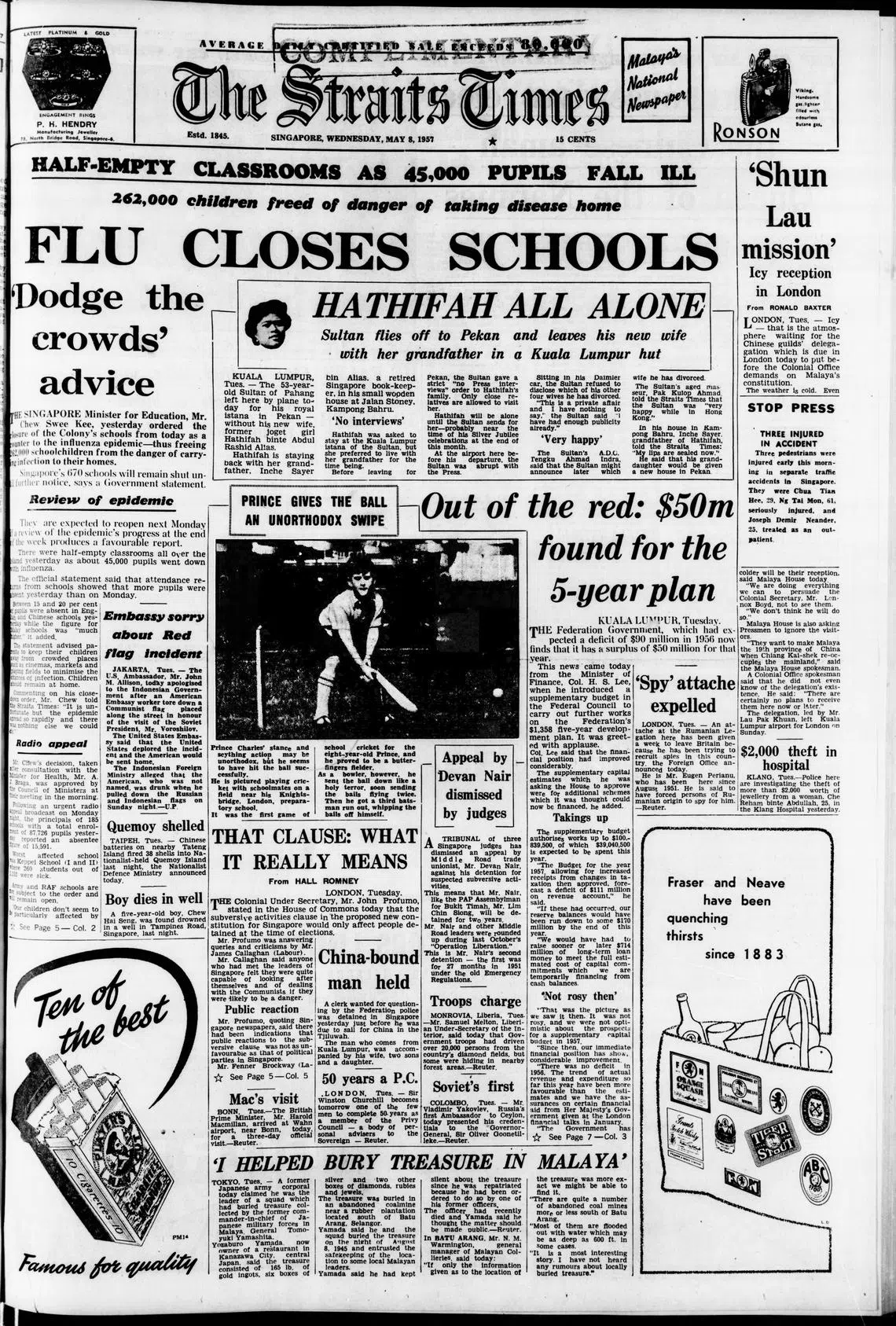

But as cases soared and tens of thousands of children fell sick, the authorities realised there was no way to avoid drastic measures.

On May 7, in the front-page story “Singapore flu scare”, the paper reported that this could be the worst outbreak in Singapore’s history.

The next day, schools were shut. One headline read: “Half-empty classrooms as 45,000 pupils fall ill”. Another said: “262,000 children freed of danger of taking disease home”. Schools were to be shut for at least a week.

On May 8, 1957, schools were shut in Singapore. One headline read: “Half-empty classrooms as 45,000 pupils fall ill”.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Countering misinformation

Fear and misinformation about diseases have long existed, as has the role the media played to counter them with fact-based reporting.

For example, during Singapore’s decades-long fight against diphtheria, a serious bacterial infection spread by coughs and sneezes or through close contact, the paper put its weight behind public health efforts to get parents to vaccinate their children.

As early as March 5, 1939, The Straits Times reported on a voluntary immunisation programme targeting one-year-old toddlers to combat the disease. But it took years to persuade parents to vaccinate their children.

On July 20, 1952, the newspaper ran a story headlined “Diphtheria war starts in S’pore”, urging parents to take their children to government clinics for free inoculations. Despite these efforts, diphtheria cases continued to go up, leading the Government to launch a formal anti-diphtheria vaccination campaign on March 1, 1954.

On July 20, 1952, the newspaper ran a story headlined “Diphtheria war starts in S’pore”, urging parents to take their children to government clinics for free inoculations.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The battle against diphtheria continued into the 1960s. On May 14, 1961, The Straits Times reported that a nationwide vaccination campaign would begin by the year end. Then Minister for Health Ahmad Ibrahim stressed the urgency of the campaign, noting that diphtheria was one of the leading causes of child deaths in Singapore, with between 50 and 60 fatalities annually out of about 600 cases.

Efforts to control infectious disease continued, and in 2003, Singapore faced one of its most serious outbreaks: Sars, or severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Sars had begun in Guangdong, China, in November 2002. Singapore’s first case was reported on March 1, 2003. The patient, a 26-year-old woman, had contracted the virus while holidaying in Hong Kong and returned to Singapore, where she was admitted to Tan Tock Seng Hospital.

Singapore’s first case of Sars was reported on March 1, 2003. On April 3 that year, the paper ran a report with the headline “91 cases traced to just one woman here”.

PHOTO: ST FILE

This case marked the start of a significant outbreak in Singapore, leading to 238 confirmed cases and 33 deaths. Worldwide, there were 8,096 known infected cases and 774 deaths between November 2002 and July 2003, when Sars was declared contained by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

The Sars outbreak in Singapore prompted swift public health responses, including the closure of schools, implementation of quarantine measures, and the setting up of a government Sars task force.

Among other things, the Government launched a $230 million Sars relief package in April 2003 to help the most affected industries, namely, the tourism and transport-related sectors.

During the Sars outbreak in 2003, thermal scanners at Woodlands Checkpoint were used to detect people leaving or entering Singapore who had a fever.

ST PHOTO: STEPHANIE YEOW

The Covid-19 virus that emerged almost two decades later was a different beast. More than seven million people worldwide, including at least 2,100 people in Singapore, have died from it.

The newsroom set up its own Covid-19 task force led by veteran journalists Karamjit Kaur and Chang Ai-Lien. They supervised the coverage across both print and digital platforms. As a public service, The Straits Times made all Covid-19-related content freely accessible online.

Ms Kaur, 54, who is now associate editor (news), says the newsroom took its responsibility of being a key source of reliable news very seriously. “Amid the national and global crisis, The Straits Times played a critical role as the go-to media platform for credible and trusted news,” she says.

“It was a heavy responsibility that the newsroom took very seriously, with timely news updates, analyses and advice from experts. It was public service journalism at its best.”

There was much confusion about the disease, recalls Ms Chang, 54, now associate news editor. “The entire newsroom worked tirelessly to help the public make sense of what was happening, the latest developments and, most importantly, how to keep themselves and their loved ones safe,” she says.

“We were all in it together, united in purpose to do our best for readers during that extraordinary time,” she adds.

In January 2022, the newsroom launched a book on the first two years of the pandemic. In This Together: Singapore’s Covid-19 Story

In January 2022, the ST newsroom launched In This Together: Singapore’s Covid-19 Story, a book on the first two years of the pandemic.

ST PHOTO: STEPHANIE YEOW

It wasn’t until April 2022, some two years into the pandemic, that the authorities significantly eased its Covid-19 measures,

An open space at Chinatown Complex, closed on Sept 29, 2021 (left), as seniors were advised to stay home during the Covid-19 pandemic; and on June 23, 2022, after Covid-19 restrictions were lifted.

ST PHOTOS: ONG WEE JIN

The pandemic underscored the critical importance of credible information and trusted public interest journalism, said then Straits Times editor Warren Fernandez in the book In This Together. “Survey after survey showed that, in Singapore as in many countries, Covid-19 contributed to a surge in audiences for trusted media titles,” he noted.

Today, that role is even more vital, as misinformation can spread faster than the virus itself, undermining public health efforts and sowing confusion.

A 2022 WHO study found that misinterpreting health information during outbreaks can heighten anxiety, increase vaccine hesitancy and delay medical treatment.

Compounding the issue are online algorithms that feed people content aligned with their existing beliefs, trapping them in echo chambers where falsehoods are amplified and mistaken for fact.

In a health crisis, this distortion of truth isn’t just dangerous, it can also mean a decision between life and death.

Joyce Teo is a senior health correspondent. She joined The Straits Times in 2004 and has been on the health beat for more than a decade. She also hosts the ST Health Check podcast.