Life After... finding out her father was hanged for drug trafficking when she was two

So much of the news is about what is happening in the moment. But after a major event, people pick up the pieces, and life goes on. In this new series, The Straits Times talks to the everyday heroes who have reinvented themselves, turned their lives around, and serve as an inspiration to us all.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

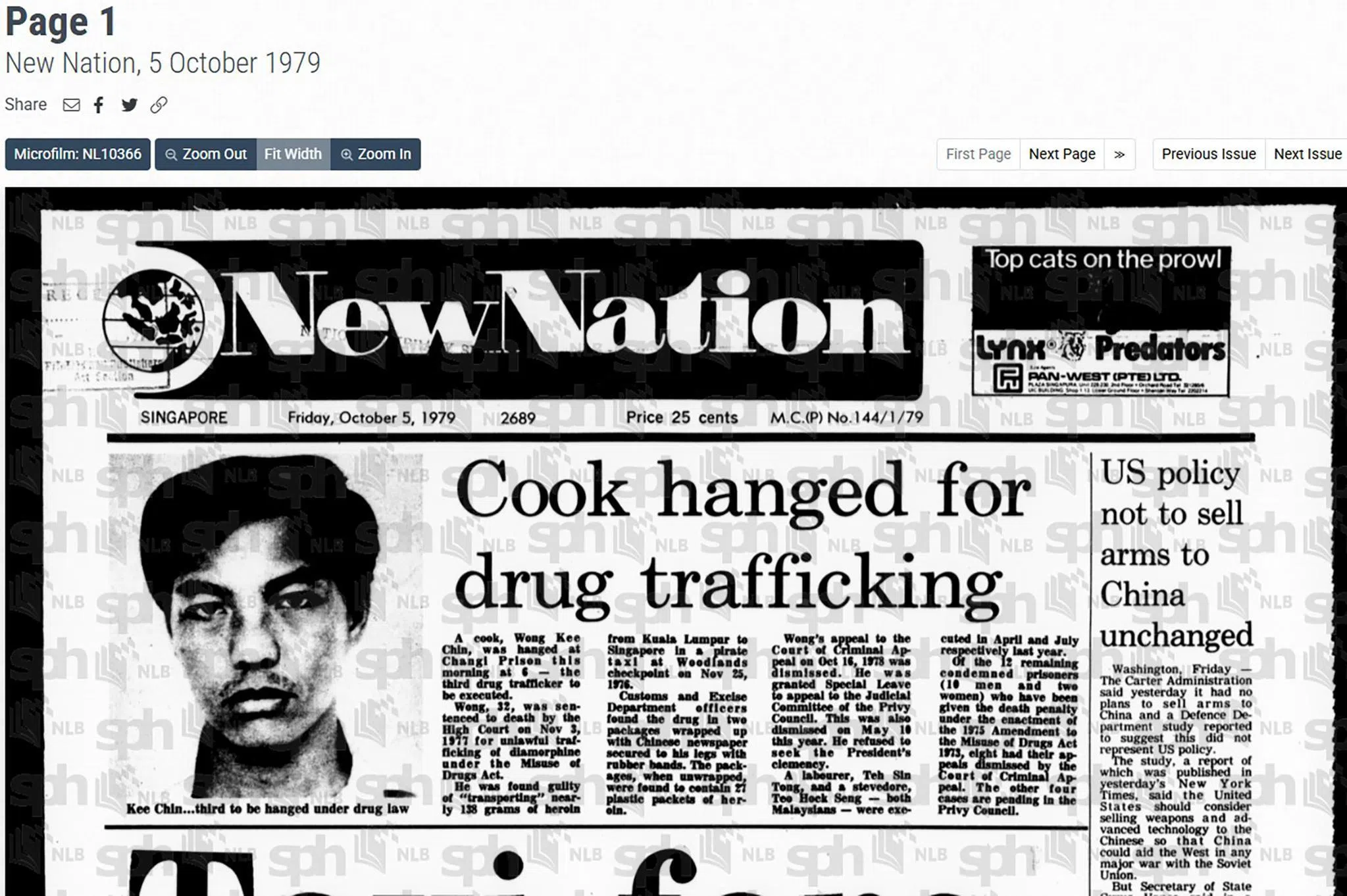

Ms Adeline Wong's father was hanged for drug trafficking in 1979, when she was two years old.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

- Adeline Wong only learned at 33 that her father was hanged for drug trafficking when she was a toddler, resulting in a childhood marked by mystery and questions about her identity.

- Overcoming personal struggles, Ms. Wong found faith, reconciled with her mother, and discovered a letter from her father urging her to do good.

- Inspired by her father's letter, Ms Wong started a social enterprise to help prisoners and former offenders through animal-assisted interventions.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – When Ms Adeline Wong thinks about her father, a faint and fragmented image comes to mind.

A man steps out of a room upon seeing his wife and young child. He carries the toddler briefly, then hands her back to her mother before returning to the room.

Ms Wong, 48, is unsure if this is a real memory.

But she believes it may have been the last time her father held her before he was sent to the gallows.

Growing up, she never knew what had happened to her father, whose death was shrouded in silence, mystery and shame.

Her mother, Ms Teng Kim Choo, 78, would break down in tears whenever Ms Wong tried to ask her about him. Relatives treaded lightly on the subject or avoided it altogether.

“Seeing my mother’s reaction, I decided to just accept it as a mystery and ignore all the questions I had,” Ms Wong told The Straits Times.

It was only at the age of 33 in 2010 that she finally learnt the truth. Her father, Wong Kee Chin, was hanged for drug trafficking in 1979, when she was two years old.

Through newly released newspaper archives, she discovered that her father, a cook, had been arrested in November 1976 for transporting nearly 138g of heroin from Malaysia into Singapore.

During his trial, he said that he was persuaded by a friend to traffic the drug in exchange for a reward of $1,000.

He was the first Singaporean, and the third person, to receive capital punishment following amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Act in 1975, which introduced the death penalty for specific drug trafficking offences. The law was further amended in 2012 to allow for judicial discretion in certain cases.

A 1977 Straits Times article described the moment the verdict was passed: “Wong, who stood in the dock with bowed head when sentence was passed, was calm but his wife, who was in court with their four-month-old child, broke down and wept uncontrollably as she was helped out of the court by relative(s).”

Hearing her father’s voice for the first time

In 2010, the National Library Board launched NewspaperSG, giving the public online access to archives of Singapore’s newspapers.

Curiosity took hold of Ms Wong when she saw the news. Alone at home, she searched for her father’s name online.

The results yielded numerous newspaper articles about him, along with photographs.

Ms Adeline Wong’s father, a cook, had been arrested in November 1976 for transporting nearly 138g of heroin from Malaysia into Singapore.

PHOTO: NEWSPAPERSG

A wave of emotions swept through her as she read the reports. Although the news did not surprise her, the thought of what her mother had to endure left her with a heavy heart.

Her parents, who were married in 1970, had tried to conceive for six years, to no avail. Her mother realised she was pregnant only after her husband was arrested.

“Imagine as a young lady – she was only 29 then – to see her own husband’s photo in the newspaper... The shame that she had to go through, and she carried through it on her own,” said Ms Wong.

“I kept wondering how she managed to go through that period of time all by herself.”

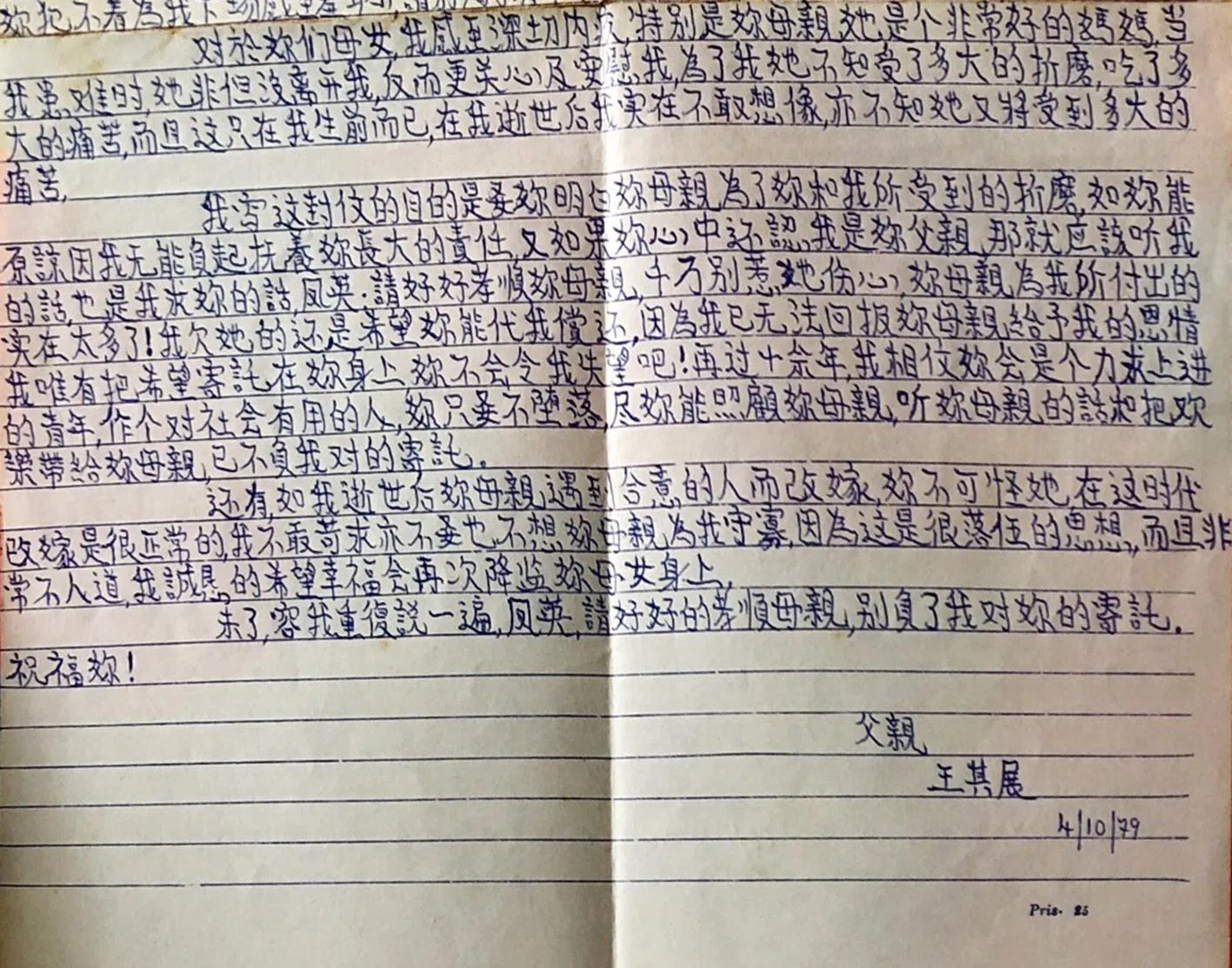

It was then that she recalled that her mother had once wanted to show her a letter her father had written for her.

In the letter, written in Chinese on Oct 4, 1979, a day before he was executed, Mr Wong urged his daughter to be filial to her mother, writing that she had suffered greatly because of him.

He also encouraged her to do good for society.

An excerpt of the letter Ms Wong’s father left behind for her.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ADELINE WONG

Reading that her father was calm when the death sentence was passed brought her comfort, assuring her that he faced death with courage. He had also found faith while in prison.

His final message to her also drove her to help people affected by crime.

“I want to bring hope to them, to tell them that although the journey they face now is very painful, one day, they can walk out of it. One day, they can help others who are facing the same issues,” she said.

In 2012, Ms Wong began volunteering for Prison Fellowship Singapore (PFS), a Christian non-profit organisation that supports prisoners, former offenders and their families. She became a full-time staff member in 2013.

While volunteering, she found out that her father was ministered to by Reverend Khoo Siaw Hua, the first honorary prison chaplain for PFS.

Strained relationships

As a child and teenager, Ms Wong had always felt distant from her mother, who worked multiple jobs as a single parent to support her family, including her father-in-law.

At the time her husband was arrested, Ms Teng was a 29-year-old homemaker.

With her husband gone, she had to find ways to put food on the table. She worked six days a week, often from 6am to 10pm, holding several jobs – as a seamstress during the day and a waitress at night.

Speaking in Mandarin, Ms Teng said: “Work was extremely tiring, but I had no choice. I just ignored my circumstances and persevered, one day at a time.”

Her long hours meant that Ms Wong lived with her uncle’s family and saw her mother only on Sundays. Ms Teng was strict, fearful that her daughter would get into bad company, as her father had.

Ms Wong as a baby with her mother, Ms Teng Kim Choo.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ADELINE WONG

This, however, created distance between mother and daughter.

As a child, Ms Wong would cry and hide whenever her mother came to visit.

“I thought that my mum didn’t want me, that she abandoned me. I was an unwanted child, which was why I lived apart from her,” said Ms Wong.

She came to see her mother as a “disciplinary mistress”.

Their relationship was so strained that Ms Wong refused to read the letter from her father as a secondary school student because her mother had insisted on reading it together.

The silence surrounding her father’s absence plagued Ms Wong throughout her childhood and teenage years, leaving her struggling with questions about herself and her identity.

In school, she became quiet and withdrawn, afraid that others would ask her about her family.

Later, in polytechnic, she began searching for the love she felt she had never received from her father.

She shoplifted, got into toxic relationships, and even tried sniffing glue, in an attempt to gain approval and feel accepted.

Everything began to unravel after a painful break-up.

“I realised that after I tried so many things, there was still a very big void in my life. I felt that life had no more meaning, no more purpose. I felt that I should end it all off,” she said.

Rebuilding what was lost

The turning point in her life came when a friend invited her to church. Finding faith made her feel loved and gave her a sense of purpose.

She also started to see her mother in a new light.

“The veil in my eyes was lifted… I realised that I had misunderstood her all along. She is a very strong woman who has gone through so much for me, which I never saw.”

Having lived apart for years, Ms Wong said she felt a strong conviction to reconnect with her mother, who had been living alone.

Ms Wong started to see her mother in a new light after going to church.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

So, in her early 20s, Ms Wong, who was living with her uncle, reached out to her mother and moved into her apartment in Telok Blangah – the first time they ever lived together.

“I know that I have this responsibility to take care of her and to rebuild our mother and child relationship,” she said.

In 2021, Ms Wong, who had previously worked in the facilities management sector and co-owned a pet grooming salon, started her own social enterprise, Human-animal bond In Ministry (HIM). It provides animal-assisted intervention to beneficiaries, including prisoners and former offenders.

A certified substance abuse counsellor and animal-assisted psychotherapist, she runs programmes and therapy sessions in prisons, halfway houses and other social service agencies.

Inmates are deeply moved when they interact with animals, she said.

“One of them told us that it has been 16 years since they last touched an animal,” she said. “Interacting with animals is so powerful. They can make people feel loved and accepted.”

Ms Wong’s social enterprise, Human-animal bond In Ministry, provides animal-assisted intervention to beneficiaries, including prisoners and former offenders.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

She also recruits former offenders to become facilitators with her organisation. Ms Wong said many face difficulties immediately after their release, including delays in getting their identity cards, which make it hard to open bank accounts or find jobs.

During this transition period, they can volunteer with HIM and receive an allowance of $50, while taking steps towards their reintegration with society.

Ms Wong believes that if her father had lived and was released from prison, he would have chosen a similar path. Both of them share the same birthday, something she believes to be an act of divine intervention.

“I see my work as continuing a legacy that he was unable to do,” she said.