Levelling the playing field: More students with special needs granted accommodations for exams

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Dr Geetha Shantha Ram and her daughter Tara, when the child was first diagnosed with dyslexia.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF GEETHA SHANTHA RAM

- Students with special needs can be given provisions like extra time for national exams like PSLE.

- About 6,700 students received such access arrangements in 2024, mainly for dyslexia and ADHD.

- Concerns exist about results slip annotations impacting perceptions.

AI generated

SINGAPORE - When Dr Geetha Shantha Ram’s daughter Tara was in Primary 3, she struggled to keep up academically.

Simple mathematical questions were a struggle for Tara, not because of poor calculation skills, but because she could not comprehend the questions.

Tara was later diagnosed with mixed dyslexia, a learning difficulty that affects both sound-based and visual processing.

Based on her diagnosis and recommendations by a psychologist, the Singapore Examinations and Assessment Board (SEAB) granted Tara extra time, larger spacing and font size when she took her PSLE.

She was also exempted from taking mother tongue language as an examinable subject.

Such accommodations, known as access arrangements (AA), are designed to support students with special educational needs during national exams – allowing their skills to be assessed without compromising assessment objectives.

In 2024, about 6,700 students were granted AA, such as extra time or support from human readers, scribes or prompters. This was up by about 60 per cent from 2015.

According to SEAB, the most common conditions among this group are dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and the rise in numbers could be attributed to more students being diagnosed with special needs.

As at 2023, there were about 36,000 students here with reported special education needs. Around 80 per cent of them were in mainstream schools, with the rest attending special education schools.

Students with dyslexia may take a longer time to read text and spell even common words, which can affect their writing pace and ability to express themselves through writing.

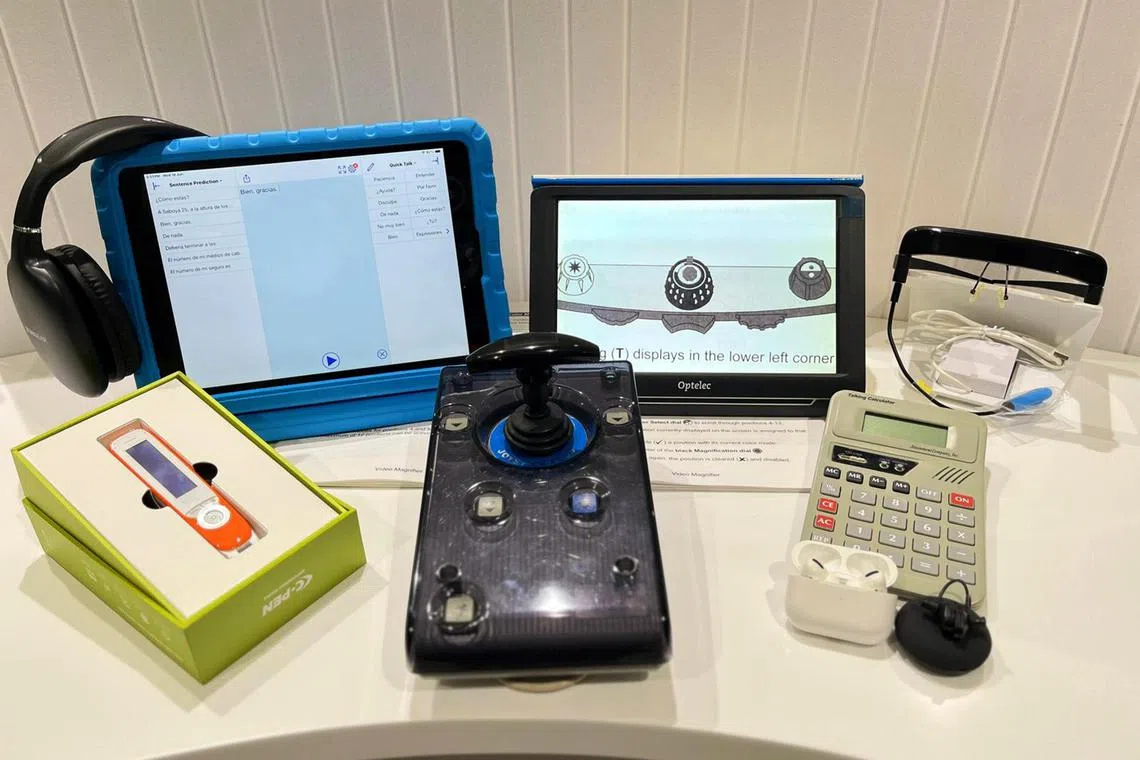

SEAB also allows the use of assistive technology such as a reader pen, which scans and verbalises written text for the visually impaired. Other tools include desktop magnifiers, word processors and screen readers.

An assortment of assistive technology apps, software and devices used in exams.

PHOTO: SPD

For national exams such as the PSLE, O levels and A levels, students can apply for AA through their school by end-February of their examination year. They will receive an outcome by April of the same year.

They are advised to approach their school’s designated special education needs officer or form teachers for assistance.

For daily class work and school-based assessments, students can also apply for AA at their school directly.

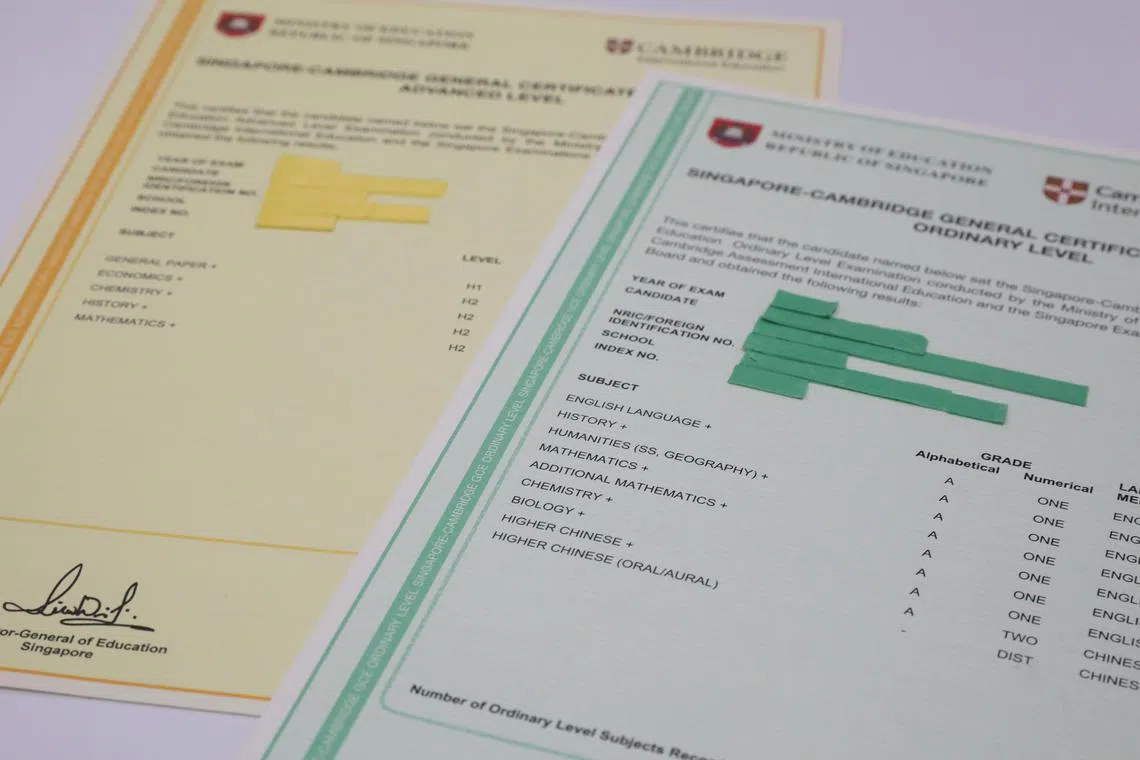

O- and A-level certificates annotated with a ‘+’ symbol to indicate that the paper was taken with Access Arrangements.

ST PHOTO: TARYN NG

Dr Geetha likens the need for such provisions to wearing glasses to compensate for poor vision.

“You wouldn’t challenge a child needing glasses if they cannot see clearly, right? An access arrangement is like these eyeglasses because now you can access the information, and demonstrate what you have learnt in a fair way,” said the director of specific learning difficulties assessment services and English language and literacy division at the Dyslexia Association of Singapore (DAS).

Over the years, Dr Geetha has seen how special arrangements, together with coping strategies such as using a ruler to prevent skipping lines, allowed Tara, now 13, to perform on a par with her peers despite her condition.

The SEAB website states that it considers both medical conditions and the school’s observations of the student’s performance, as well as difficulties faced during school and examinations under standard conditions.

Applicants must submit medical documentation, including a formal diagnosis from a registered medical professional and any supplementary reports such as assessment outcomes and therapy reports.

In cases of unforeseen circumstances such as injuries or sudden medical conditions which happen just before or during examinations, the same evaluation framework will be used to assess the need for AA.

Student Matthew Ng, who is currently a software engineering intern, had been granted extra time, a scribe and a separate room to sit his exams since primary school.

This allowed him to do well in the mainstream school system despite having dystonic cerebral palsy, which affects his gait and fine motor skills, including writing.

“If not for all these (provisions), we wouldn’t be able to prove our competency,” said Mr Ng, 24, who is an Asia Pacific Breweries Foundation scholar at local charity SPD.

Mr Matthew Ng, 24, has dystonic cerebral palsy which affects his gait and fine motor skills.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF MR MATTHEW NG

Any stigma attached?

Ms Moonlake Lee, founder of local charity and social service agency Unlocking ADHD, said families with neurodivergent children in mainstream schools often worry about the stigma and potential impact on future opportunities when seeking exam accommodations.

This is because SEAB annotates results slips to reflect any exemptions or accommodations, though it does not disclose medical conditions or specific support provided to third parties.

Ms Lee said such concerns should not prevent parents and students from getting the help they need, which “may hinder (the children) from showing what they are capable of”.

Dr June Siew, head of DAS Academy, which trains individuals who support children with special needs, said that students are concerned about what their peers would think of them if they have special provisions.

She recalls her 15-year-old son, who has both dyslexia and ADHD, feeling ashamed about having such arrangements.

“A simple statement like (the teacher asking) those with AA to raise their hands sets (them) apart and might make other students think: Why are you so special? Why do you have this unfair advantage?” she said.

“I don’t blame the teachers, because it’s an administrative thing. But if teachers can just add a simple one-liner to explain why these children need access arrangements, it might be helpful in setting the correct tone and help their peers develop empathy.”

Exemptions not the easy way out

Aside from special exam accommodations, students can also be granted exemption from certain exam components or a subject should their special needs significantly impair their ability to show knowledge and skills, such as oracy skills.

In such cases, the student’s overall subject grade will be computed based on his performance in other components.

For Ms Jasmine, who declined to provide her last name, her son with autism spectrum disorder, now 13, has been granted both extra time and exemption from taking Chinese since he was in primary school.

The school was initially unwilling to grant this request.

“I suppose there are genius kids who just want to get away with (not taking) Chinese. This is very hard to spot,” said the 50-year-old art teacher.

The problem for her son was finding the courage to speak.

“I recall telling the teachers that I’ll be very thankful if you can make him speak Chinese, because if the anxiety kicks in, (he) won’t speak to you at all,” said the mother, who recorded instances of his increased heart rate and him breaking his eraser during Chinese lessons, reflecting his dysregulation.

“(For students with special needs), it’s not because they don’t know. Some are sensitive to sounds, some have physical challenges or get anxious, so access arrangements are very important to them.”