On a freezing July night in 2009, Mr Benjamin Skinner met a dying 16-year-old in a state-run hospice in Bloemfontein in South Africa.

Three months pregnant, Sindiswa also had full-blown Aids and tuberculosis. Originally from the impoverished district of Indwe, the orphan was hoodwinked by a woman who promised her work.

Instead, she was sold to a Nigerian drug- and human-trafficking syndicate in Bloemfontein.

She was forced to walk the streets for 12 hours every night.

"She was systematically raped and tried to run away twice, but got captured because some of her clients were police officers.

"They kicked her out when she could no longer stand up," recalls Mr Skinner who was in South Africa to investigate sex trafficking for Time magazine.

He listened to Sindiswa's story while mopping sweat from her fevered brow.

He says: "When I became a journalist, I wanted to see the world and wanted someone to pay for it.

"But sitting there and listening to a young girl give you, through halting breaths, her last testament imbues you with a sense of responsibility not just to tell her story accurately, but to try to find as many others before they end up like her.

"You want to get their stories out and help end the crime of slavery."

And that is what he has been doing for the last decade. And boy, does he have stories to tell.

In Uttar Pradesh in India, he met a victim of debt bondage working in a quarry, hacking rocks into sand for food and pennies.

He was working to pay off a loan of just 62 cents his grandfather took way back in 1958.

In Haiti, a man - just one of many traffickers who procure children from impoverished rural families by promising free schooling and a better life - approached him in a side street in Port-au-Prince and asked him if he wanted a 12-year-old to do housework and be a sex slave.

The price: just US$50 (S$69).

He says: "I have a principle about never paying for a human life.

"But what I did after this was to head for the hills where the children were pulled from and talked to the villagers and asked them why they were sending their children to these 'courtiers'."

Many of them, he adds with a sigh, really thought they were giving their children a better shot at life.

Mr Skinner - who was in Singapore last week to discuss human trafficking and slavery with civil society and non-governmental organisations - has written more than 50 articles on the subject for publications including Time, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times and the Miami Herald.

He is also the author of A Crime So Monstrous: Face-To-Face With Modern-Day Slavery, which contains his research on and stories of slaves, survivors, traffickers and abolitionists from all over the globe.

Winner of the 2009 Dayton Literary Peace Prize for non-fiction, the book, according to American book review magazine Kirkus Reviews, boasts "investigative journalism of the first order, the kind that demands blood tribute".

Mr Skinner agrees with Professor Kevin Bales who defines slaves as "those who are forced to work, held through fraud, under threat of violence for no pay beyond subsistence".

Besides being professor of contemporary slavery at the University of Nottingham, Prof Bales is also co-founder of human rights outfit Free the Slaves and lead author of the Global Slavery Index, which estimates that there are 45.8 million slaves in the world today.

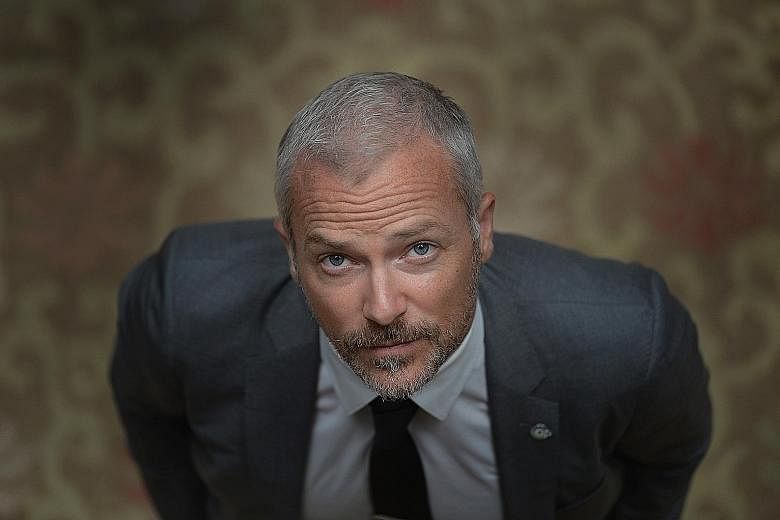

In a quiet room at the Regent Singapore hotel, Mr Skinner, 40, cuts a distinguished figure with his salt-and-pepper hair and his sharp grey suit.

His passion to eradicate slavery is perhaps not surprising, given his background.

"From the beginning of the 19th century and even going back to the 18th century, I had relatives who were Quaker abolitionists who went up on soapboxes to speak out against slavery," he says.

The Quaker movement believes that every human being is of unique worth, and is big on social justice and human rights.

Born in Wisconsin in the United States to a British colonial officer who became the chair of the African Studies programme at the University of Wisconsin and an administrator, he grew up attending Quaker meetings.

"We were very liberal.

"We had gay marriages in the 1980s when they were not even honoured by the state and talked more about Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman than we did about Jesus and Moses," he says, referring to the famous abolitionist icons.

Because his father's work involved stints in different countries, his childhood was peripatetic.

"When I was two, we moved to northern Nigeria which is now Boko Haram territory," says Mr Skinner, who also spent time in China, Japan, Yemen and Mexico.

The exposure, he says, did him a lot of good.

It helped him understand different cultures, planted the seeds of wanderlust and whetted his appetite for adventure.

"It also gives you a certain empathy when you're the only white kid in Nigeria. Having said that, it's a different reality for a white person in northern Nigeria than it is for a northern Nigerian in Wisconsin."

Thanks to his parents, he developed political consciousness early in life too.

"I remember we had refugees from the Guatemalan civil war living in our house. My mother felt very strongly that these were people targeted by the death squads in their country and they needed to be given safe passage," he recalls.

In his teens, he spent a lot of time in Mexico where his mother was involved in projects for the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organisation working for peace and social justice.

"I volunteered in a place for children whose parents were in jail. It got me interested in Spanish and Latin American politics," says Mr Skinner, who went on to major in Spanish, Latin American studies and sociology at Wesleyan University in Connecticut.

Upon graduation, he landed a job at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York City.

"I totally lucked out. I didn't have any contacts and applied blind, but the person who hired me was from Yale and liked rowers and I was a rower. It was hardly meritocratic," he recalls with a chuckle.

In 2001, the late Richard Holbrooke - a distinguished American diplomat who was also special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan - took him on as one of his youngest proteges.

"He pulled me on board to help him formulate his thoughts on a memoir he was going to write, but he got busy. It was like a fellowship: I got a regular income from him but was allowed to do my own writing."

His foray into journalism started with lifestyle pieces, including one on hip-hop culture in Cuba. But a tip-off from an activist organisation led him to write his first piece on slavery for Newsweek in 2002.

The piece chronicled the experiences of a former slave master as well as a former slave in Mauritania in North Africa.

It led him to want to know more about modern-day slavery and that, of course, changed his life.

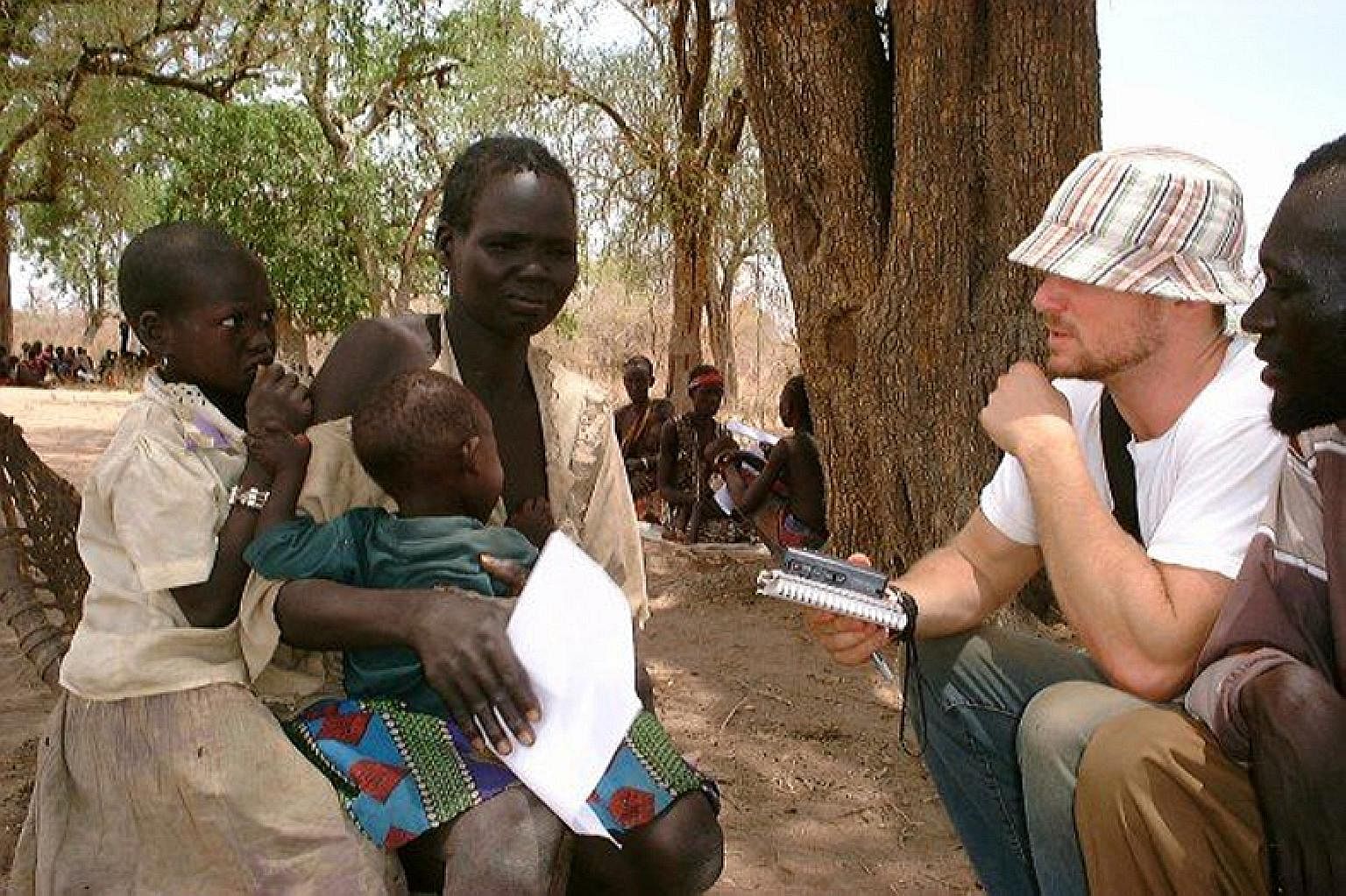

The next year, he persuaded Newsweek to let him fly to the front lines of the Sudanese north-south civil war where slavery and human trafficking were "booming industries".

"They said OK because I was crazy enough to do this for US$1,000 when the airfare alone was a lot more," says Mr Skinner, who also had a grant of US$3,000 from a small foundation in Minnesota.

In Sudan, he met Mr Muong Nyong, a 27-year-old slave who ran barefoot for two weeks across the desert after escaping his captors.

"I told myself, 'This subject is much bigger than a couple of articles. This feels like a book.'"

Publisher Simon & Schuster was intrigued enough to give him an advance. The enterprising man also got in touch with several foundations to support his work.

"Foundations are a lifeline for journalists," says Mr Skinner who got funding from, among others, Humanity United, the Open Society Foundations and The Stardust Fund.

It allowed the intrepid writer to "pull up a map, pull out a pen, circle an area and just turn up there".

"I knew I won't be able to document every single slave.

"I wanted to tell some representative stories of different types of slavery in different industries in different geographies and allow them to speak for the wider problem," says the writer whose research took him to five continents, and countries like Haiti, Romania, Moldova, Turkey, the Netherlands and India.

Although Mr Skinner tries to adhere to the journalistic practice of observing but not engaging, he has not always been successful.

After a Haitian woman begged him for help to rescue her 12-year-old daughter who was abused by her owner, he set out with two burly men to save her.

"There was thankfully no violence, we got her out safely," says the abolitionist, who went on to pay for the child's education for the next 11 years. "She's doing great. She wants to be a doctor. It's the greatest investment I've ever made," he says with a smile.

A Crime So Monstrous was released in 2008 to great reviews by the likes of The New York Times and The Washington Post.

One of National Geographic's Adventurers of the Year 2008, Mr Skinner was also recognised as a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum in 2011.

He went on to co-found Tau Investment, a private equity fund which invests in inefficient supply chains to change them into ethical and sustainable businesses.

Right now, his energies are focused on Transparentem, which he also founded. The non-profit uses investigative reporting and front-line forensic methods to highlight human and environmental abuses in supply chains.

It sends to major brands and retailers intelligence reports about the activities of their direct and indirect suppliers. A grace period is given for remedial action against highlighted problems. If none is taken, these reports will be disclosed to investors and the public.

"We really try to proselytise the idea that information is opportunity," he says.

To lick the problem that is slavery, he says, a lot still needs to be done. After all, there are more slaves today than at any other time in history.

"In all likelihood, I'm not going to bury this problem in my lifetime, and I know that I can't do this on my own," he says.

But he wants to play a role in helping to end slavery.

"I interviewed my father quite a bit before he died two years ago. He kept using the word service, service to others. This is echoed in the lives of many other people I admire.

"I try to emulate that. The acquisition of personal wealth and glory is fleeting. But the satisfaction that comes with serving others can be extraordinary."