It Changed My Life: From banker to bank cop

Economist wants to help shape public policies to help consumers

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

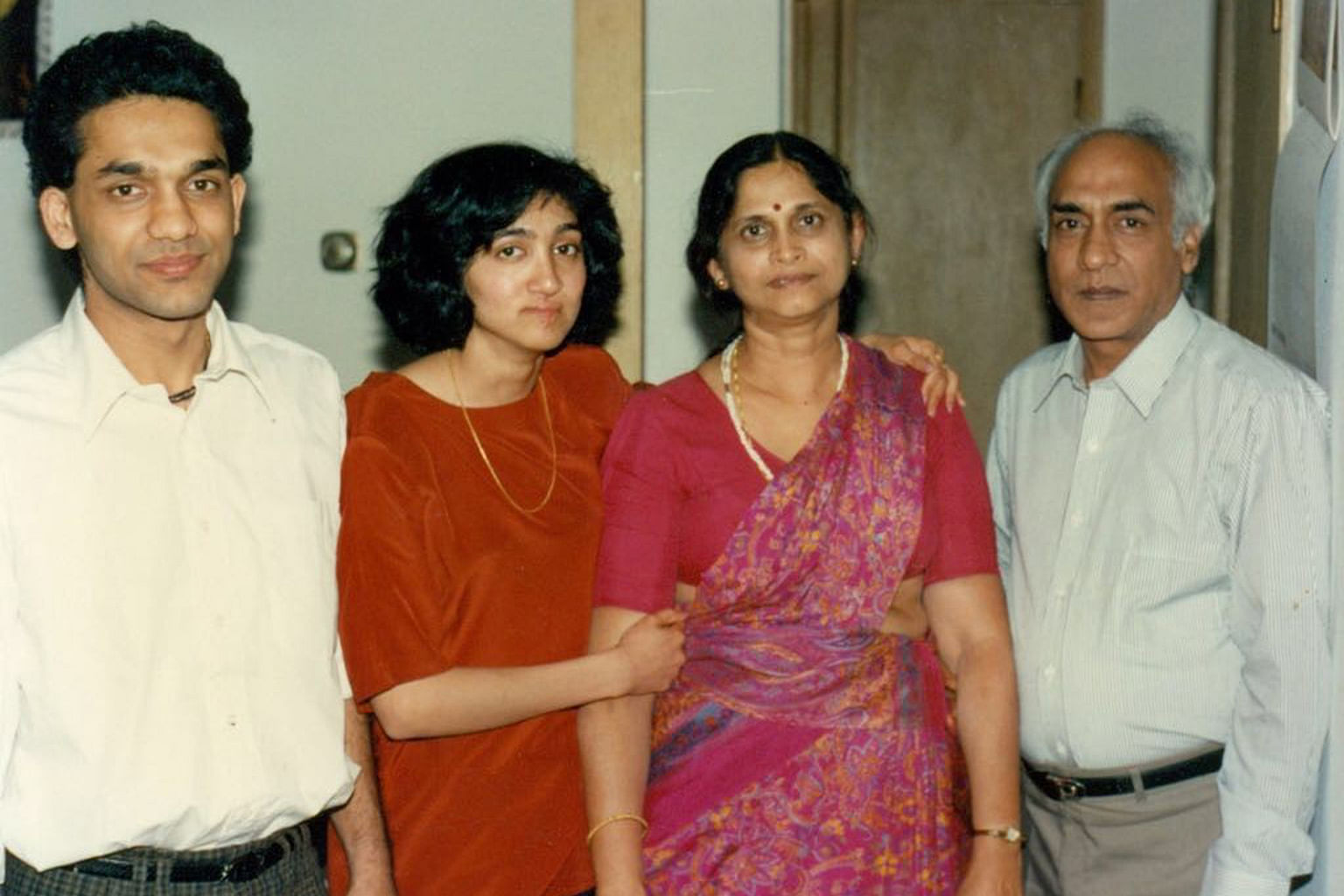

Prof Sumit (above) conducting a masterclass at NUS Business School last year, and with his younger sister and parents in Uganda in 1992. The family moved to Africa when his father was working there as an economist with the World Bank.

PHOTO: SUMIT AGARWAL

If you can't beat them, well... you join someone who can. That was what Professor Sumit Agarwal did during the 2007-2009 global financial crisis.

"I was first involved in creating the crisis and then in solving it," says the vice-dean of research at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School.

For six years until 2006, he was an executive handling risk management and capital allocation at a leading American bank in the United States; his input helped to shape some of the high-risk complex financial products which contributed to the market meltdown.

"I was not way up on the totem pole but, by year five and six, I was clearly vocal in telling the bank that our capital ratios were way too low and our default rates were way too high," he says.

When his protests fell on deaf ears, he decided he had to get out. Taking a massive pay cut, he joined the Federal Reserve, the central bank of the US which had to come up with a panoply of measures to calm the tumult.

"Since I came from the banks, the Fed used me to go after the banks. I was the right guy, I knew where the bodies were buried," says Prof Sumit, 46, who was a senior financial economist at the Federal Bank of Chicago until 2012 .

By then, he was so plugged into the study of consumer behaviour and the role of regulators that he decided he needed to expand his research into different terrains beyond banks. "I wanted to shape public policies to protect consumers," he says simply.

And that is just what he has been doing. His research findings have appeared in top academic journals and been used in policy decisions by government agencies globally, including Consumer Financial Protection in the US and the Ministry of Manpower in Singapore.

For instance, he and his team discussed their research on the spending patterns of retirees with policymakers involved in the Silver Support Scheme, which supports the income of the bottom 20 per cent of retirees.

Since joining NUS five years ago, he has won the institution's Outstanding Researcher Award twice, in 2013 and this year.

In more ways than one, he is following in the footsteps of his late father, who worked on policy problems as an economist with the World Bank.

Lithe and trim, the elder of two children spent the first six years of his life in a small town in Uttar Pradesh in India.

His father started out as an accountant handling contracts in the Indian civil service; his mother was a housewife. Both came from big families.

Contractors and businessmen hoping to land tenders always tried to grease his father's palms but he was straight as an arrow.

"A contractor bought ice cream for my sister and me when we were walking around Shimla one day," says the chatty professor, referring to the famous Indian hill town. "When my father saw that, he threw the ice cream away and said, 'This is the guy who applies for the tenders I prepare. He can't just give my children ice cream.'"

When Prof Sumit was six, his father uprooted the family to Africa.

"My sister was born with a cleft palate. My father wanted the best treatment for her but because he refused to take bribes, he decided he had to get a job which paid more. He took a World Bank job in Africa, working on privatisation and stabilisation policies," he says.

Their first stop was Tanzania, where he attended school in a small town in Iringa. "I had to learn Swahili and ended up repeating a year."

After a few years and a stint in Dar es Salaam, they moved to Kampala, the capital of Uganda.

"It was a tough country. Idi Amin had just been kicked out and there were coups in the country," he says, referring to the late Ugandan president, notorious for his brutal regime and crimes against humanity during his reign from 1971 to 1979.

"I went to school with a bodyguard who was armed with a machine gun. He'd drop me off and take me home. Because my father worked at the World Bank, I was a potential kidnap target," he says, adding that armed robbers entered the family home late one night and carted everything of value away.

He has vivid memories of another evening when his father decided to go for a drive with the bodyguard and took him along. He saw more than 200 bodies dumped in a ditch.

"It made me think about instability and the role of government, and a lot of my research now grew out of the things I saw," he says.

That included huge wealth disparity. His family had good housing provided by the World Bank but many of his Ugandan friends in school lived in mudhouses.

"You'd see people on the streets who didn't have a place to live in and the average person lived on a measly $1 per day," he recalls.

In his teens, his parents sent him to boarding school in Uttar Pradesh, for his secondary education. Then it was off to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UW-Milwaukee), where he read computer science on a World Bank scholarship.

With a grin, he wonders if he would have been another Satya Nadella if he had continued studying computer science. The chief executive of Microsoft also studied computer science and was his contemporary at university.

His father, however, told him that economics was the way to go. "He said computers were just a tool. He had all these colleagues who would come visit in Uganda and they were working all over the world solving global and policy problems. They told me, 'Why don't you study economics? There are more important questions to answer than writing code and other computer stuff.'"

And that was how he ended up with his master's and doctorate in economics, also from UW-Milwaukee. "Typically, one would move to other institutions but my sister was also in Milwaukee and my parents told me to take care of her, so I did," he says.

His dissertation was on how banks can create economic development.

After graduating in 2000, he landed a job with an American bank. As a risk management executive, he did empirical analyses of data which his bank used to formulate different financial products.

"Those were the days when bankers would go out for dinner and spend US$10,000 on a meal or US$4,000 on a bottle of wine. They were making a lot of money," says Prof Sumit, who was invited on more than one occasion by senior managers to such dinners.

Pretty soon, however, he realised that what the banks were up to was bad and "horrible". His protests to his bosses, however, were in vain.

"They said we were too worried about numbers. They'd say, 'Don't worry, we don't hold the risk. Some hedge fund in China or Germany is holding the risk; it doesn't bother us.' They didn't understand that these things would come back and bite them," says Prof Sumit, who was a senior vice-president when he left the bank in 2006.

He took a 50 per cent pay cut and joined the Fed instead.

He says: "My bank colleagues were going, 'You have dramatically risen in six years and you are going to become a financial economist and write papers on how to regulate banks? What is wrong with you?'"

For him, however, it was a homecoming, following in the footsteps of his father who died in 2011.

At the Fed, he zoomed in on banking malpractices and how banks were exploiting the lack of financial literacy of some consumers.

An example, he says, was how they pushed adjustable-rate mortgages - loans with variable interest rates - on people about to retire.

"It was irrational and it was cheating because there's no way the income of these people would increase," says Prof Sumit, who became an American citizen in 2009 and whose input helped to shape many Bills.

He left the Fed in 2012 after being offered a job by NUS. His move to academia came about for several reasons.

Divorced from a Japanese banker, the father of a six-year-old girl wanted to be closer to his widowed mother who had moved back to India. And he wanted more freedom to do research on issues beyond banking, such as the environment.

"I wanted to see how I could make people's lives better in terms of their wider interactions across different terrains," he says.

Prof Sumit, who is also a professor in the departments of Economics, Finance and Real Estate, lost no time plugging himself into research, using behavioural and consumer economics to get to the root of issues: Can covered walkways help to reduce one-stop commuting and put less pressure on our transport systems? Will installing meters in bathrooms lead to more prudent use of water? Does the siting of staircases in buildings have a bearing on lift usage?

"I believe if you are in a country, you should help to solve the problems of that country. I think I should be held accountable to the taxpayers of this country, who pay my salary," says the researcher, who interacts regularly with officials from different ministries.

"When regulators understand what you are doing and take action, it is very rewarding. As a researcher, if what you do ignites even a spark..." he says, breaking into a big smile.

Now on leave from NUS, he is in Georgetown University in Washington doing research on several issues, including ObamaCare, and whether this health reform law introduced by President Barack Obama in 2010 caused higher unemployment or birthed many benefits.

The interview is over. The yoga enthusiast has to get to his yoga class. He strides briskly past the lifts. He is taking the stairs.

And walking the talk.