The longer Covid-19 patients stay in ICU, the weaker they get, says S'pore doc

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

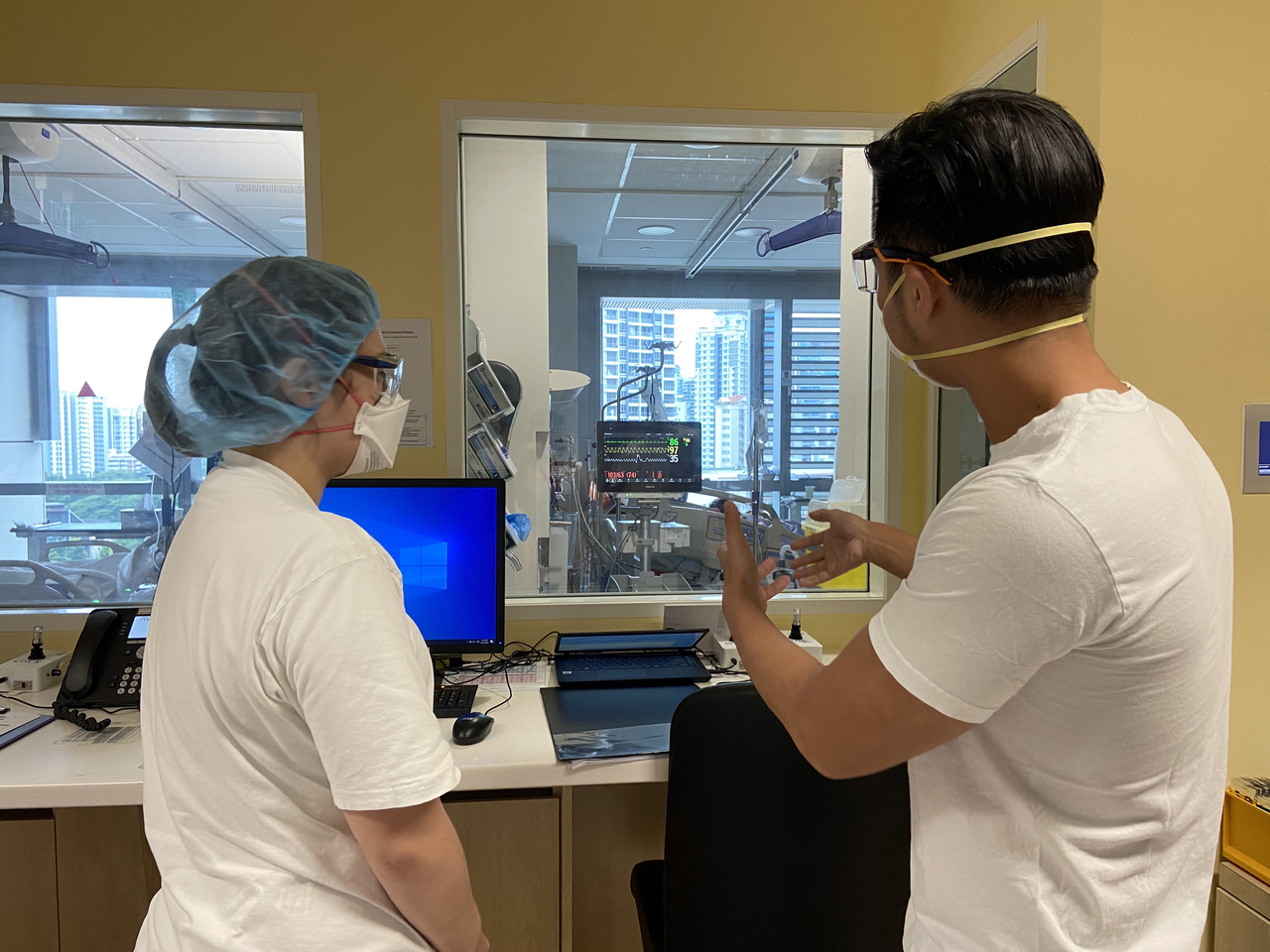

Dr Puah Ser Hon (right) with senior staff nurse Queennie Lee in a Covid-19 ICU ward.

PHOTO: NATIONAL HEALTHCARE GROUP

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE - Dr Puah Ser Hon often does a little jig before starting his shift in the Covid-19 intensive care unit (ICU), hoping it will bring a bit of luck that day, with all patients stable and on the road to recovery.

"We all hope for a quiet day. Some say prayers; I do the jig. Everyone has personal ways," said the expert in respiratory and critical care medicine, who started in ICUs as a trainee in 2011 and became a consultant in 2015.

But not all days are quiet.

There are peaks and troughs, he said. Things get hectic when several new patients are admitted at the same time, or if one patient deteriorates very quickly and requires a lot of attention.

The 20-bed ICU at the National Centre for Infectious Diseases - NCID has four ICUs now with 20, 18, 10 and six beds - has two teams of doctors comprising a consultant, a senior resident and several medical officers, supported by a team of nurses.

On a normal day, patients who get very sick in a general ward are assessed by an ICU doctor, and if critical care is needed, the patient will be transferred to ICU.

On a bad day, very sick Covid-19 patients are also admitted directly from the emergency department.

They would have been rushed to hospital because they suffered a heart attack or stroke, but on admission, they might be found to have Covid-19, and are admitted to the outbreak ICU at the NCID.

"We triage those who require more urgent attention first. If necessary, we will ask for help," said Dr Puah.

Doctors like him, who are trained to care for critically ill patients, will rush over from clinics or hospitals wards.

Though he is an ICU doctor, Dr Puah spends one to two weeks a month working there and the rest of the time in the other wards and clinics - which are nearby so that he can rush over if suddenly needed.

While all patients in the ICU are seriously ill, their conditions may be very different.

No two patients who need a ventilator to help them breathe, for example, are identical. So a respiratory physician like Dr Puah needs to "interpret the lung mechanics" to know if it is stiff, filled with fluid, and so on.

A respiratory therapist, an allied healthcare ventilator specialist, will then ensure that the ventilator, which takes over the breathing for the patient, is calibrated exactly to the patient's requirements.

While he can manage most critical conditions, Dr Puah said that when he has any doubts, he would turn to other specialists, such as a renal physician or cardiologist if a patient's organs deteriorate, or a haematologist or infectious diseases specialist should the patient also have a secondary infection on top of Covid-19.

While he tries to save every life, he said it is also important to ask patients who have severe medical conditions what their wishes are.

The longer a patient stays in the ICU, the weaker they get. And even after recovery, they may not enjoy the quality of life they had before and become fully dependent on others for everything.

Treatment in the ICU can also be very uncomfortable, with a tube down the mouth to help with breathing. This means the patient would not be able to eat or drink, so another tube is put through the nose to provide feeds.

As they care for the patients and interact with their families, strong attachment sometimes occurs and it is painful when the patient dies, said Dr Puah.

The reward is when they recover. He said: "It's a bit like the movies. Patients who were very sick at the stormiest part of their stay, when they get better and move out of the ICU, that's quite something."

Even better he said, is to see pneumonia patients walking into his outpatient clinic for a follow- up check-up after discharge.