Successful gene therapy on child with rare Parkinson’s disease offers hope for other patients

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Spanish girl Irai, who was diagnosed with aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency, after the treatment (right) when she was seven years old.

PHOTOS: The AADC RESEARCH TRUST, COLUMBUS CHILDREN'S FOUNDATION

Follow topic:

- Irai, diagnosed with rare AADC deficiency (paediatric Parkinson's), received successful gene therapy in Poland, enabling her to walk, talk and thrive.

- Viralgen uses modified viruses to deliver genes. Its AAV production has a massive capacity, reducing costs and increasing gene therapy accessibility.

- Phase 3 trials for Parkinson's gene therapy are underway in Asia-Pacific, offering potential one-off treatment, but require complex trials and expertise.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – A few weeks after Spanish girl Irai was born, it became clear that something was wrong.

She could not hold up her head or move her limbs, and as she grew older, she could not speak or eat properly. Her body stiffened and she was often in pain.

Irai was later diagnosed with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency – better known as paediatric Parkinson’s disease – an extremely rare condition with only 130 to 200 known cases worldwide.

With the condition having far fewer treatment options than adult Parkinson’s disease, Irai’s parents were desperate. Through Fundacion Columbus, a non-profit foundation dedicated to improving the lives of children with cancer and rare genetic diseases in Europe, her parents were connected with scientists pioneering gene therapy research.

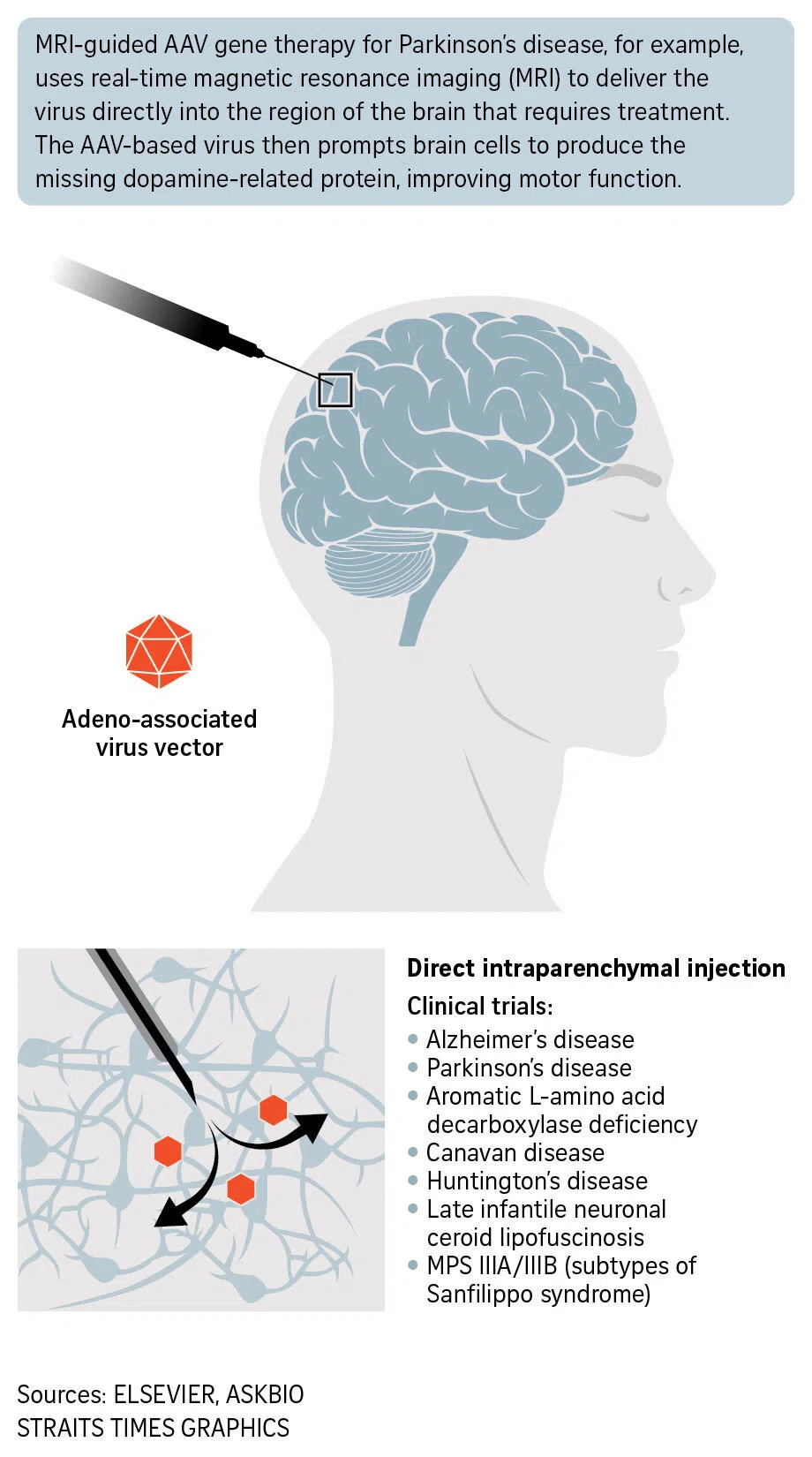

The novel treatment, called adeno-associated virus (AAV) therapy, uses a modified, harmless common cold virus to deliver healthy genes into a patient’s cells to treat genetic diseases.

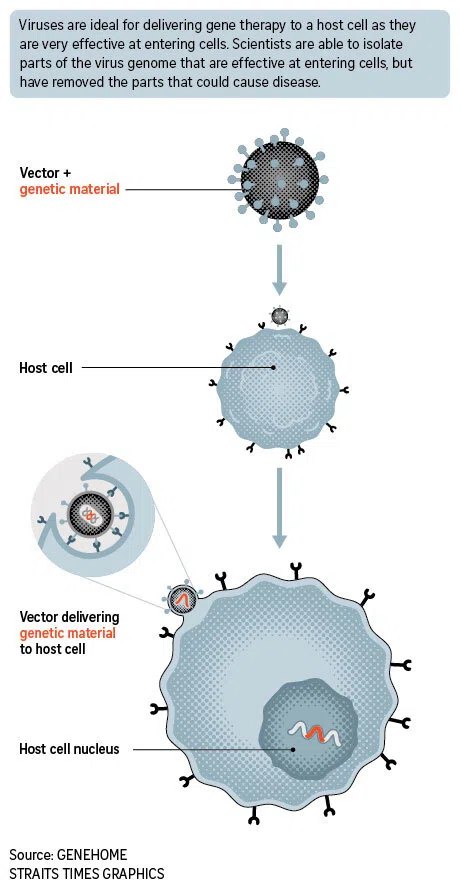

Researchers engineer AAVs to carry therapeutic DNA and inject them into the body. These vectors or carriers then target specific cells, release their genetic cargo, and prompt the cells to produce the missing or faulty proteins, offering a functional cure.

The AAVs are produced by Viralgen, which specialises in large-scale production for cell and gene therapies. It is part of AskBio, a leading clinical-stage gene therapy company under German multinational life science giant Bayer.

In May 2019, Irai, then four years old, underwent the therapy in Warsaw, Poland.

Neurosurgeon Krystof Bankiewicz, guided by magnetic resonance imaging, injected the modified virus with genetic material into Irai’s brain.

This procedure enabled her brain to produce the necessary neurotransmitters – or chemical messengers – which led to rapid progress in her motor and cognitive functions.

By the age of seven, Irai was walking, talking and laughing, thriving as a pre-schooler. Today, at 11, she can even ski.

The success of her treatment has led scientists to explore using AAV therapy to treat the larger population with Parkinson’s disease, a progressive neurological condition affecting adults aged 60 and over.

The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease has doubled over the past 25 years. Today, more than 10 million people worldwide are estimated to be living with the condition, making it the world’s second-most prevalent neurodegenerative disease, after Alzheimer’s disease.

In Singapore, the condition affects three in every 1,000 Singaporeans aged 50 or above. While there is currently no cure, medications, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, lifestyle changes and sometimes surgery can help manage the symptoms.

Viralgen chief executive officer Jimmy Vanhove told The Straits Times that successful gene therapy needs three main components: optimised vectors; promoters, which are DNA sequences that control when, where, and how much a therapeutic gene is activated inside target cells; and disease-specific therapeutic transgenes, which are the genes injected into a patient’s cells to treat a condition.

“We use non-pathogenic viruses as vehicles to deliver missing or damaged genetic material into the patient’s cells. Once the gene is repaired, the patient’s body will begin to produce the proteins or substances needed to combat the disease,” he added.

Viruses are ideal for delivering gene therapy to a host cell as they are very effective in entering a cell.

Viralgen’s state-of-the-art facility, located in San Sebastian city in Spain, can manufacture up to 2,000 litres of the AAVs for gene therapy.

AskBio chief executive officer Gustavo Pesquin said that this massive production capacity is key to reducing costs and making gene therapy more accessible.

However, the total time needed to produce one gene therapy is at least 20 weeks.

AskBio has received the Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration.

Phase 2 trials are ongoing to assess the effectiveness and safety of the treatment in 127 patients in the US, Germany, Poland and Britain.

At the same time, the company has started the third phase of human testing and is recruiting patients for the clinical study in Asia-Pacific countries.

“If we are talking about Asia, by 2050, almost one in four (people) will be above 60, and they will all come with many comorbidities – neurological disorders and cancers – that will increase significantly,” said Mr Ashraf Al Rouf, who heads commercial operations for Asia-Pacific at Bayer Pharmaceutical Division.

“The treatments have advanced extremely well so far, and the precision is extremely high,” he said.

The focus now is to introduce the treatment to more people, with the goal of providing a one-off treatment that could bring gene therapy closer to a cure for certain diseases, he added.

Professor Tan Eng King, senior consultant in neurology at the National Neuroscience Institute (NNI) in Singapore, said Parkinson’s disease is “relatively unique as the predominant initial defect involves a loss of specific neuronal cells in the midbrain”, resulting in a loss of dopamine. The brain chemical plays a key role in regulating feelings such as pleasure and motivation, the body’s movements and other functions.

“This (initial loss in neuronal cells) gives doctors a window of opportunity to intervene, especially in the early stages,” he told ST.

He said that while gene therapies are promising, the processes remain complex as they involve the use of a viral vector carrying genes that can help produce dopamine or protect neurons.

Due to the complexity, initial trials usually involve a very small number of patients, and everyone knows who gets the therapy or a placebo, said Prof Tan, who is also deputy chief executive officer of academic affairs at NNI.

The Phase 3 study will provide more robust evidence that the positive results observed are not due to a placebo effect, he noted.

“We are certainly ready to participate in these kinds of studies if companies are keen to bring them (to Singapore) as we have the neurological, neurosurgical and neuroimaging expertise,” Prof Tan said.