Medical Mysteries

Saving face: He’s had four major operations since he was 1½ to make him look ‘normal’

Medical Mysteries is a series that spotlights rare diseases or unusual conditions.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Mr Tobie Goh, 23, was diagnosed with Crouzon syndrome as a baby, and has undergone four major operations in the past 20 years.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

- Tobie Goh, diagnosed with Crouzon Syndrome at infancy, underwent four surgeries from age 1½ to 23. The rare genetic disorder caused skull bone fusion, impacting brain growth and facial development.

- Multidisciplinary teams, including neurosurgeons and plastic surgeons, performed surgeries to relieve brain pressure, reposition forehead and midface, and correct his underbite. Orthodontic treatment managed teeth misalignment.

- A fifth surgery is planned to refine Tobie's eye sockets and nose. Now 23, Tobie can breathe properly and is training for a half-marathon after previously struggling with strenuous exercise.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – Since the age of 1½, Tobie Goh has undergone not one but four major operations to make him look “normal”.

And the team of surgeons is planning for a fifth: to move his lower orbital rim bones, which form the lower border of the eye socket, forward as well as carve down the nasal cartilage graft and refine his nose.

There were already troubling signs at birth – the shape of Tobie’s head was abnormal and his eyes were bulging. Doctors also noticed that his mid-face had sunk inwards.

He was diagnosed with Crouzon syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that causes the fibrous joints between a baby’s skull bones to fuse too early, resulting in inadequate space for the brain to grow.

A baby’s skull is made of several bones joined by flexible sutures and soft spots called fontanelles, which allow it to flex during birth and expand as the brain grows.

The suture line in the front usually fuses in infancy, while the rest fuse when the person is in their 20s.

But in patients with Crouzon syndrome, one, two or more sutures fuse during infancy.

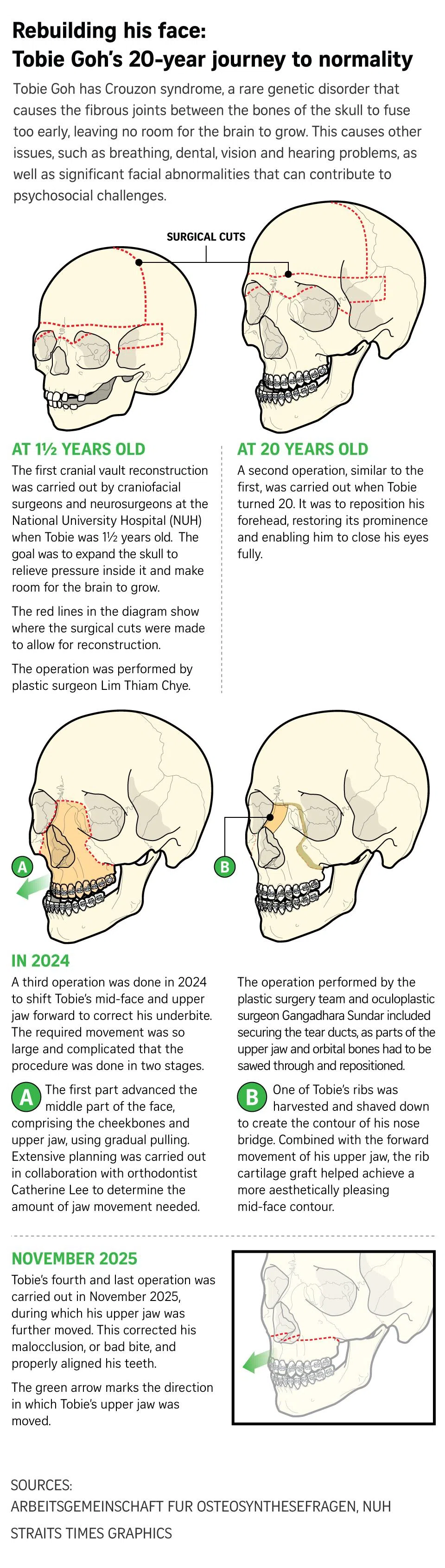

As baby Tobie’s brain was being compressed, he underwent surgery in 2003 performed by Associate Professor Lim Thiam Chye, a senior consultant with the plastic, reconstructive and aesthetic surgery division at the National University Hospital (NUH), to create room within his skull.

Prof Lim and another surgeon reshaped the child’s skull to improve his head shape and increase the intracranial volume to allow for normal brain development.

Baby Tobie’s forehead and upper eye sockets were also moved forward to correct prominent eyes and forehead retrusion, a condition where the forehead bone is positioned further back, creating a backwards-sloping profile.

Neurosurgeon Vincent Nga, who was part of the team correcting adult Tobie’s skull, explained that the pressure on the brain in a patient with Crouzon syndrome can be life-threatening.

“The first two years of the child’s life is the most critical because that is when... the brain is rapidly growing.”

This is why cranial surgery is often timed around one year of age, when the brain is still rapidly developing, he added.

During the operation, one of the neurosurgeon’s most critical tasks was cutting through the skull, a step that requires extreme care to avoid damaging the dura – the brain’s outermost protective membrane that also contains major blood channels.

“Any injury to the dura or the blood channels within it could be catastrophic,” he said.

Since that first operation, Tobie has been receiving ongoing care from the multidisciplinary team, comprising plastic surgeons, neurosurgeons, an ophthalmologist and a craniofacial orthodontist.

For instance, Adjunct Associate Professor Nga monitored Tobie’s neurodevelopment.

As pressure from the growing brain increases, development of functions like speech, fine and gross motor skills, and even social interactions may be affected, he said.

Some medical studies showed that Crouzon syndrome affects approximately one in 25,000 people worldwide, manifesting in the first year of life.

The key effects of the condition include sleep apnoea, vision issues, hearing loss and potential increased brain pressure.

Mr Tobie Goh (centre) posing with the NUH team of surgeons who helped rebuild his face. They are (from left) Associate Professor Lim Thiam Chye, Dr Elijah Cai, Adjunct Associate Professor Vincent Nga, Adjunct Associate Professor Gangadhara Sundar and Dr Catherine Lee.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

It takes a village to manage Crouzon syndrome

Managing Tobie’s Crouzon syndrome was “a delicate art, requiring patience, finesse and planning from a multidisciplinary team, as Tobie’s facial structure continues to change and his functional needs evolve with each stage of life”, said Dr Elijah Cai, a plastic surgeon with NUH.

Tobie, now 23, recalled: “My eyes were protruding so I could not close them fully, which led to dryness.

“I also could not breathe properly and had to start using a bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) machine while I slept when I was about five or six years old.

“In addition, I had an underbite, which made chewing and speaking difficult.”

A BiPAP machine is a non-invasive ventilator used to help with breathing by delivering pressurised air through a mask: higher pressure for inhalation and lower pressure for exhalation.

Said Dr Cai: “(The whole reconstructive surgery) was like a 3D jigsaw puzzle.

“Every dimension is important, as any error in the movement would affect the other dimensions. A lot of planning was involved.”

Tobie underwent a second operation, which was similar to the first when he was a baby, at the age of 20.

This time, it was to better reposition his forehead, restoring its prominence and enabling him to close his eyes fully.

Adjunct Associate Professor Gangadhara Sundar, a senior consultant with the Department of Ophthalmology at NUH, said he was there during Tobie’s adult operations “to babysit the eyes”.

“Because the eye sockets right below the brain are underdeveloped and shallow, the protection of the eyes is not there. Also, it affects the muscles around the eyes, causing squints.

“When this is not picked up and treated, the patient may become blind from lazy eyes.

“Behind the eye where the socket meets the brain, with the bony changes, it may get squished and damage the optic nerves causing blindness,” he said.

Prof Sundar said the child could be going blind without anyone knowing.

He added that a combination of conventional surgical procedures, together with modern technology such as 3D-printing, computer-assisted surgery and Virtual Surgical Planning (VSP), are what made such rare and complex surgery safer and more predictable for such conditions.

A third operation was performed in 2024 to shift Tobie’s mid-face and upper jaw forward to correct his underbite.

Adults with Crouzon syndrome often undergo mid-face surgery to improve breathing, protect the eyes and enhance facial aesthetics.

The required shifting was so large and complicated that the procedure was done in two stages.

The first part advanced the middle part of the face, comprising the cheekbones and upper jaw, using gradual pulling.

This required extensive planning, which was carried out in collaboration with craniofacial orthodontist Catherine Lee to determine the amount of jaw movement needed.

The operation performed by the plastic surgery team included Prof Sundar, who secured the tear ducts, as parts of the upper jaw and orbital bones had to be sawed through and repositioned.

“When the bones are cracked with no attention paid to the tear ducts, then the children are left with a lot of tearing, sticky or crusty eyes, which may result in more complex surgeries,” he said.

In the second stage of the third operation, one of Tobie’s ribs was harvested and shaved down to create the contour of his nose bridge and achieve a more aesthetically pleasing mid-face contour.

Adults with Crouzon syndrome often undergo midface surgery to improve breathing, protect the eyes, and enhance facial aesthetics.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

Dr Lee, a visiting consultant at NUH, first saw Tobie when he was nine.

She explained that in Crouzon syndrome, the premature fusion of sutures happens not only in the skull alone, but also in the face, where there are numerous sutures which normally fuse when the child is about 12.

The fusion affects the bones of the upper jaw, which support the teeth and connect to the sinus area, she said. The upper jaw stops growing, but the bottom jaw continues to, resulting in misalignment.

She said that when a child’s adult teeth begin to emerge around the age of 11, premature suture fusion can cause problems such as crowded teeth, delayed eruption, missing teeth, or occasionally extra teeth.

“My job is to reduce the severity of the problem,” she added.

To address the correction of the mid and lower face, Dr Lee said “we developed a long-term plan that incorporates both surgical and non-surgical interventions. Our proactive strategy has enabled us to minimise the complexity of his jaw surgery, reducing it to a single jaw rather than a more complicated two-jaw operation”.

She also got the young Tobie to wear a custom-fitted face mask during many years of his growth period, to guide the development of his upper and lower jaws, reducing the discrepancies in jaw length.

The operation then focused on advancing the upper jaw and mid-face, avoiding the need for a more intricate two-jaw surgical procedure during his fourth operation that would have involved setting back his lower jaw bone – “a fortunate outcome, especially considering his sleep apnoea”, Dr Lee added.

His fourth operation was performed last November, during which his upper jaw was further moved. This corrected his malocclusion, or bad bite, and properly aligned his teeth.

When The Straits Times team met him, Tobie barely displayed the features of someone with Crouzon syndrome. Yet the team of surgeons is planning for his fifth and perhaps final operation, this time to move his lower orbital rim bones forward as well as carve down the nasal cartilage graft and refine his nose.

While there is no concrete date set for this operation, Tobie has plans to get a job after graduating in accountancy.

In the meantime, he is training for a half-marathon in April.

He had never been able to do strenuous exercise as a child due to difficulty in breathing properly.

“I am looking forward to running my first half-marathon. As for making a certain timing, I have not decided what it is yet,” he said confidently.