More in Singapore choosing to make advance care plans

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

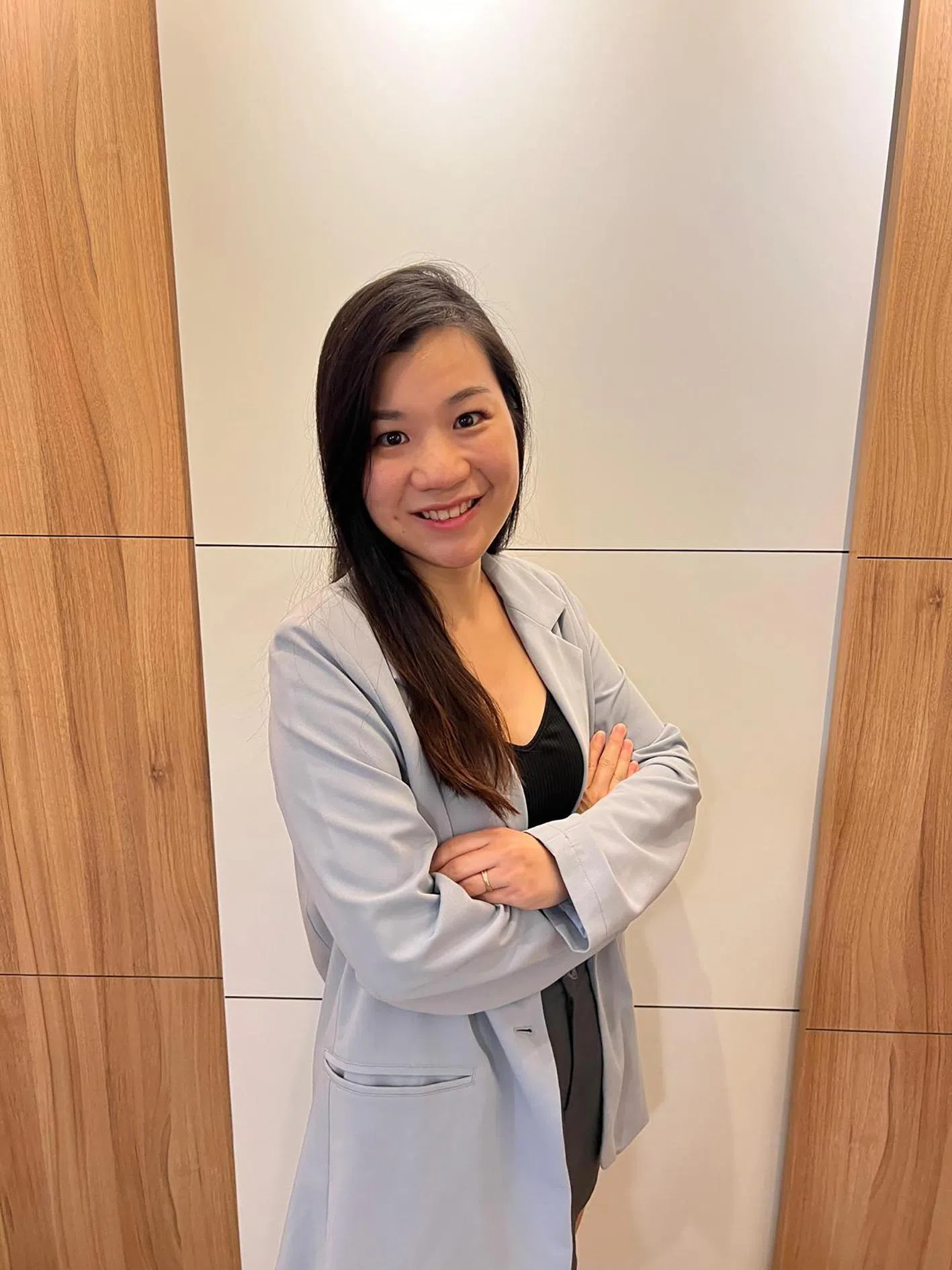

Global product manager Michelle Tan with her mother, Madam Tong Ee Mooi. A severe allergic reaction five years ago prompted Ms Tan to draw up a will, and in March 2022, she made an advance care plan.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF MICHELLE TAN

SINGAPORE - Five years ago, Ms Michelle Tan was in the middle of a conference call at home when she suddenly had difficulty breathing, with her throat feeling as if it was inflamed.

“I thought this was it, I was just going to die on the spot,” said the 42-year-old global product manager.

Ms Tan, who lives alone, said she had to make her own way from her Hougang flat to a clinic, where she was given an adrenaline injection and subsequently taken in an ambulance to a hospital.

She told The Straits Times that the incident – an allergic reaction whose cause doctors were unsure of – was an “awakening” for her.

She started to make plans for the future, including going to a lawyer to draw up a will. In March 2022, she went to the non-profit Society of Sheng Hong Welfare Services to make an advance care plan.

Advance care planning allows people to document their medical treatment preferences in advance, in line with their goals and values.

It also allows them to designate someone to decide on medical care for them in the event they become mentally incapacitated.

People can approach public hospitals and polyclinics, as well as certain social care providers, to make such a plan.

It differs from other documents such as advance medical directives – which inform doctors that you do not want to use any life-sustaining treatment in cases where death is imminent – in that it is not legally binding.

Among the preferences Ms Tan indicated in her plan were to be in a quiet, peaceful environment should she fall critically ill, as well as to have rituals performed in line with her Buddhist faith in such a situation.

She is one of an increasing number of people in Singapore who are making an advance care plan.

According to a 2019 report by the Institute of Policy Studies on end-of-life care policy here, about 5,100 advance care plans were completed between 2011 – when Singapore’s national advance care planning programme started – and 2015.

This number has jumped to more than 36,600 as at end-May 2023, said Ms Winifred Lau, chief of the primary and community care department at the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC).

The advance care planning process provides a safe space for people to share their personal care preferences, reducing the stress of decision-making on their family members, said Ms Lau.

Global product manager Michelle Tan, pictured with her mother Tong Ee Mooi, made her advance care plan with non-profit organisation Society of Sheng Hong Welfare Services.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF MICHELLE TAN

“It also ensures that their preferences are heard, especially when they can no longer speak for themselves,” she added.

Ms Lau attributed the rise in applications to several factors, such as the work done by AIC and other organisations to raise public awareness of advance care plans, as well as an “encouraging trend” of people becoming more comfortable with discussing end-of-life matters.

She pointed to a 2019 Singapore Management University study, which surveyed more than 1,200 Singapore residents aged 21 years and older, across different age groups and ethnicities.

The study found that 53.3 per cent of those surveyed were comfortable discussing end-of-life matters and issues concerning their own death, compared with just 36 per cent in 2013.

Ms Chin Shih Yuin, a programme coordinator at Sengkang General Hospital who helps facilitate advance care plans, said that when she started her current role in 2018, people greeted the concept with shock.

Ms Chin Shih Yuin, a programme coordinator at Sengkang General Hospital, helps facilitate advance care planning for patients.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF CHIN SHIH YUIN

“Some of them, their first reaction will be, ‘Why are you approaching me? Am I very sick?’” said the 36-year-old.

People are now more receptive to the idea, with the hospital receiving more calls asking how to get such plans made, she said.

Speaking at the 8th Advance Care Planning International Conference in May, Second Minister for Health Masagos Zulkifli identified several areas which could be improved to get more to participate in advance care planning.

These include getting healthcare professionals to have conversations on the matter as part of routine care, he said.

Ms Chin acknowledged that the process of facilitating advance care planning is not without challenges.

These include situations where patients disagree with their families on whether they should be resuscitated, or where patients themselves are unprepared to make decisions on their care preferences.

Patients are not pressured to make decisions on such matters, she said.

“But hopefully, by starting off the conversation, we can plant a seed, and then help the patients start thinking of their preferences.”