Medical Mysteries

Life rewired: Deep brain stimulation curbs excessive, involuntary movements in boy with rare disorder

Medical Mysteries is a series that spotlights rare diseases or unusual conditions.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Adrian is the first paediatric patient with GNAO1 in Asia to undergo Deep Brain Stimulation surgery for this condition.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

- Adrian, 11, was initially misdiagnosed with cerebral palsy due to rare GNAO1 mutation causing movement issues and developmental delays.

- After a severe bout of Influenza A worsened his condition, genetic testing revealed GNAO1, leading to deep brain stimulation surgery.

- The surgery, led by Dr Nicolas Kon, successfully stopped Adrian's jerky movements, improving his condition by 90%, allowing him to return to school.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – Fewer than 500 people worldwide are known to have a rare genetic disorder called GNAO1 mutation, which disrupts brain signalling and affects movement and development.

So it is no wonder that 11-year-old Adrian’s involuntary, jerky movements and developmental delays were initially attributed to cerebral palsy – a group of conditions affecting movement and posture caused by damage in the developing brain, most often before birth.

His mother Felicia Tan, 43, told The Straits Times that he was born prematurely at 34 weeks and was in the neonatal intensive care unit for three weeks.

“It was a non-event except for a hole in his heart that was resolved with medication,” she said.

But when Adrian was nine months old, he was not hitting any of the milestones typical for babies his age. He was not sitting up without support, crawling or babbling repeated syllables like “mama, mama”. “He was also non-communicative, and was initially diagnosed with cerebral palsy and treated as such until he was 10 before being referred to KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH),” Ms Tan said.

His condition got serious when he was infected with influenza A in June 2025. He developed high fever and bad tremors that started from his legs.

“We took him to NUH, which was the closest to our home. He tested positive for influenza A and was given Tamiflu and discharged,” his mother said, referring to the National University Hospital.

Despite the medication, Adrian remained sick, “lying very still on his bed”. “He could not move or sit up. Then, close to two weeks later, the abnormal repetitive shaking started from his legs. They were not under his control... He was so stiff we could not even fit him into his wheelchair,” she added.

That was when Ms Tan’s sister-in-law, who works at KKH, introduced her to paediatric neurologist Simon Ling. Adrian was admitted to the hospital in mid-2025, and he underwent genetic testing.

In July, he was diagnosed with GNAO1 mutation, which affects a group of proteins, turning them into molecular “switches” in the brain and disrupting normal signalling.

Doctors said children with this condition often suffer from severe movement disorders, muscle stiffness, and developmental delays – symptoms that closely resemble those of cerebral palsy. Only genetic testing can confirm it.

According to medical literature, the first children with GNAO1 were diagnosed only 12 years ago in 2013 by a Japanese research team studying DNA mutations in four Japanese children. After Adrian’s diagnosis, Dr Ling introduced Ms Tan to Dr Yeo Tong Hong, a visiting paediatric neurologist at KKH, who felt that the boy was the right candidate for deep brain stimulation surgery.

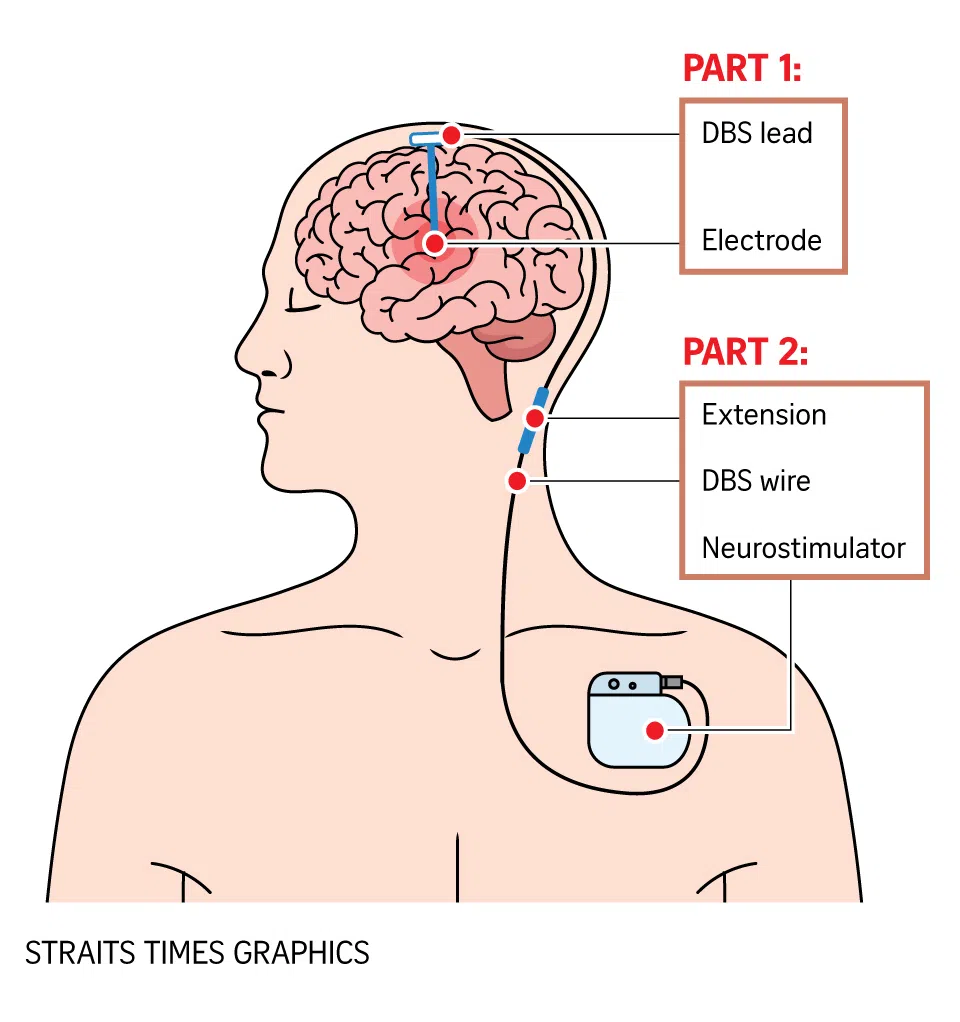

“It is an advanced treatment that involves placing two very thin wires (electrodes) into specific areas of the brain. These wires are connected under the skin to a small (battery-operated device) usually placed in the chest or the abdomen,” said Dr Yeo, who practises at Parkway East Hospital. The device is about the size of an Apple smartwatch face.

Adrian and his mother Felicia Tan with neurosurgeon Nicolas Kon from Mount Elizabeth Hospital (left) and Dr Yeo Tong Hong, a paediatric neurologist from Parkway East Hospital.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

Called a pulse generator, it sends tiny electrical signals to help correct the brain’s activity and reduce symptoms, especially dystonia, a movement disorder characterised by involuntary, sustained muscle contractions that cause repetitive twisting or jerking movements and abnormal postures. The device works “much like how a heart pacemaker works”, neurosurgeon Nicolas Kon explained.

Since deep brain stimulation helps manage movement symptoms, it is also used to treat Parkinson’s disease when medications become less effective. Studies have shown that it tends to be most effective in primary dystonia, a group of movement disorders caused by specific genetic changes.

“In these cases, brain scans usually look normal, with no injury or scarring, and treatment response rates can be as high as 90 per cent,” Dr Yeo said.

In Adrian’s case, his condition was complicated by severe, life-threatening episodes of uncontrollable, excessive involuntary movements and dystonic storms. The latter is a life-threatening medical emergency involving continuous, severe, generalised muscle spasms and involuntary twisting movements, Dr Yeo said.

Having looked after the first Scottish GNAO1 patient who underwent deep brain stimulation in Scotland when he was a consultant paediatric neurologist at the Royal Hospital for Children in Glasgow, Dr Yeo told ST that the surgery was Adrian’s only hope of living a normal life.

“I was prepared to advise his parents to let him travel to either Britain or the United States for the operation. Then I learnt of Dr Kon, who is the only surgeon in Singapore who is specialised enough to carry out the procedure (in a child),” he said.

Dr Kon, whose practice is at Mount Elizabeth Hospital, said the surgery is not for everyone.

“We did not know how Adrian would respond and there was always that chance he would not. We are just glad the surgery worked for him,” he said.

Dr Kon noted that time was of the essence as the boy had been in the intensive care unit at KKH for a long time and “was not responding to medical treatment and developing complications”.

Adrian was transferred to Mount Elizabeth Hospital, where the four-hour surgery was done on July 19. He is the first paediatric patient with GNAO1 in Asia to undergo the procedure.

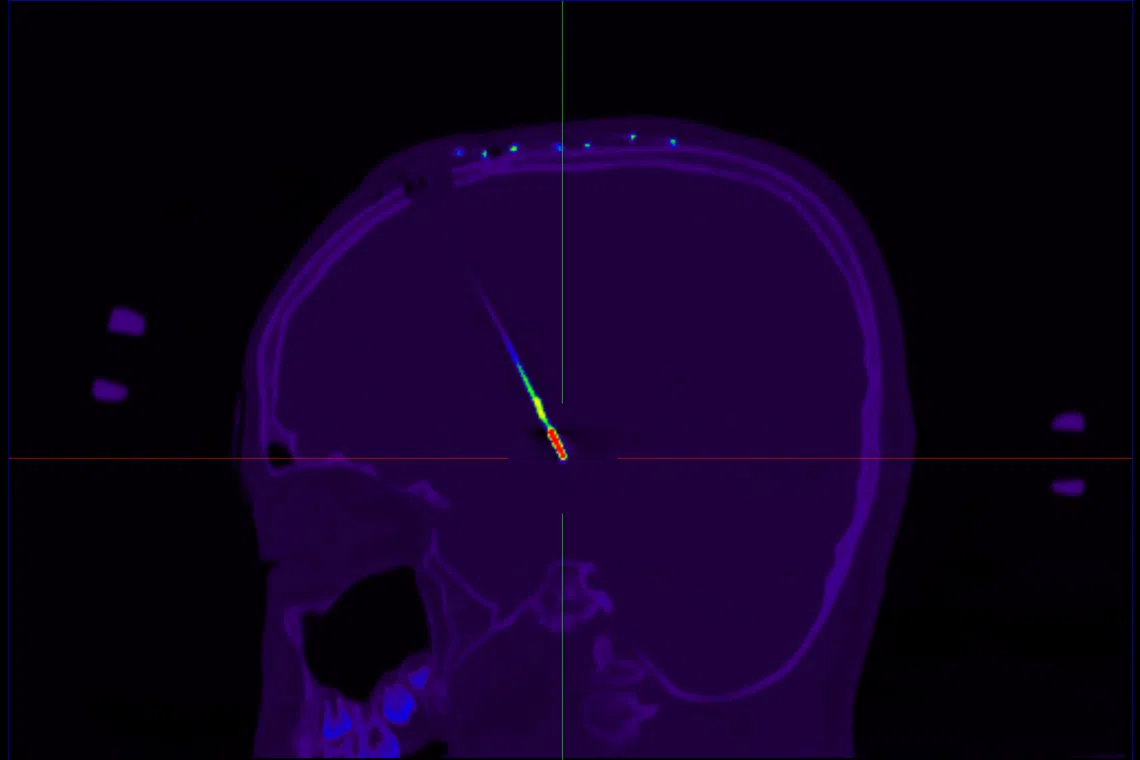

“Two electrodes, guided by CT scans and MRI to pinpoint the exact location, were inserted 7cm into the specific areas of his brain. We had to put in two electrodes as both sides of the brain were affected,” said Dr Kon. “We were worried at the same time because Adrian was on several medications to manage his refractory dystonia and movement disorder.”

The small pulse generator was implanted under the skin below the collarbone in the chest, with a wire tunnelled under the skin to connect it to the electrodes in the brain.

When the device was switched on, Adrian’s jerky movements stopped. “That was when we knew it would work for him and in a matter of time, it would help manage his condition,” Dr Kon said.

The battery, which must be recharged weekly, is designed to last 15 years before it needs to be replaced. It is charged wirelessly using an external device that is placed over the implanted battery.

Ms Tan said: “Adrian would have to keep very still during recharging so we would do it at night while he is asleep.”

Four months and several physiotherapy sessions later, he was back at school. Adrian, who uses a walker, has fewer involuntary movements now.

“We are very grateful to the doctors who worked relentlessly to pull Adrian back to his normal self and I hope by telling his story, parents will become aware and have their children genetically tested for unexplained conditions. This way, they will then find the right medical help for them,” Ms Tan said.

Deep brain stimulation

In deep brain stimulation (DBS), a surgically implanted device is used to send electrical pulses to specific areas of the brain to help control symptoms of neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease and, most recently, GNAO1 mutation. By regulating abnormal brain activity, DBS can reduce symptoms like tremors, stiffness and slowness of movement.

The deep brain stimulation surgery is performed with the child under general anaesthesia for the entire procedure.

It generally takes between four and six hours to complete.

The side view of Adrian’s head, showing a DBS electrode implanted deep in the brain.

PHOTO: DR NICOLAS KON

Two-part surgery:

Part 1: Placing the electrodes in the brain

During the first part of the surgery, DBS wires were placed in the movement centre of the brain using a specialised GPS system.

Adrian then had a CT scan and the images were combined with the MRI scans taken before surgery, creating a digital model of the brain.

Using this model, the exact location to place the DBS wire was finalised.

A small hole was drilled through the skull on one side and a tiny test wire was passed into the brain, towards the planned DBS target.

Brain signal recordings were then used to check if the wire was in the correct spot.

The test wire was then replaced with a permanent DBS wire. This procedure was repeated on the other side of the brain.

Part 2: Connecting extension wires and the battery device

In the second part of the surgery, the extension wires and the battery device were placed under the skin.

They were then connected to the DBS electrodes.

The extension wires were passed behind the ear and down the neck towards the battery device, which is usually placed over the left side of the upper chest.

Post-surgery

Adrian was given antibiotics and pain and anti-nausea medication intravenously to reduce pain and the risk of wound infection.

In the days after the surgery, the child underwent a CT scan to check if the DBS system was intact and in the correct location.

The neurologist switched on the DBS therapy before the child went home to allow him to get used to living with it. Further adjustments will be made during regular appointments.