KKH sees surge in children with genetic disease that may lead to early heart attack and stroke

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

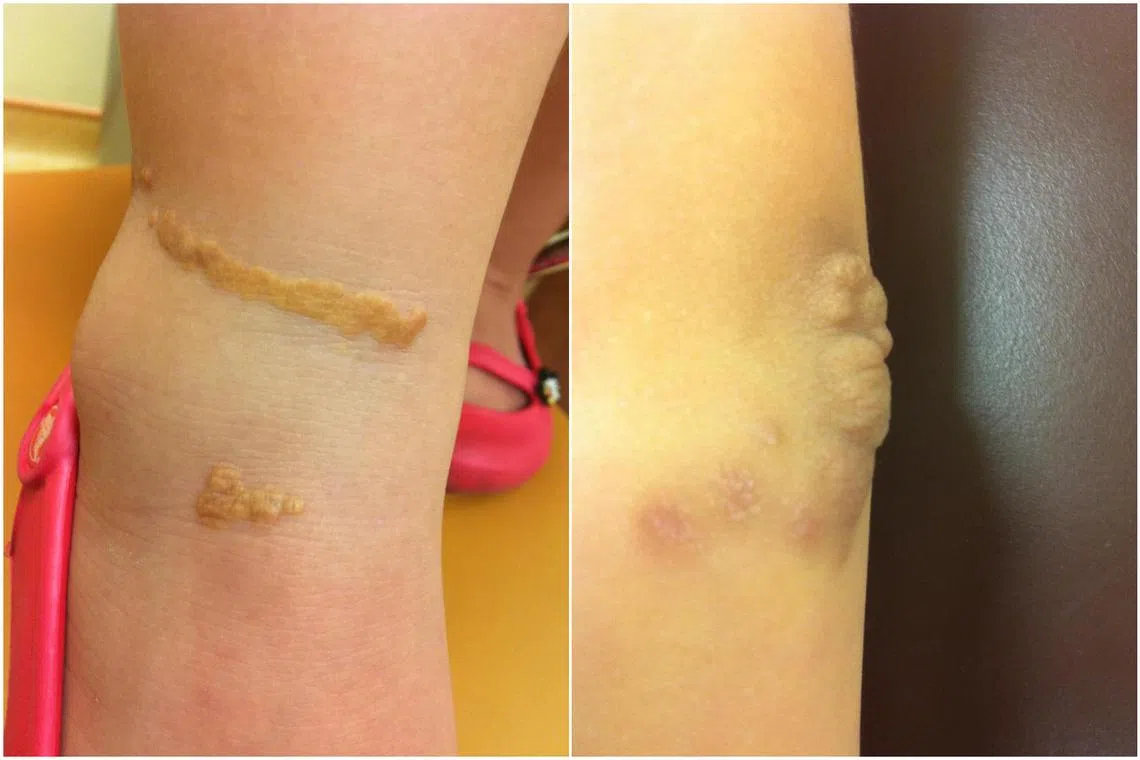

Children with the genetic disorder of familial hypercholesterolaemia may have visible symptoms such as skin bumps or lumps at their elbow.

PHOTO: KK WOMEN’S AND CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL (KKH)

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE - KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH) saw an increase in 2025 in the number of children seeking treatment for a genetic disease that could lead to heart diseases or strokes in people as young as in their 30s.

New cases of familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) reported at the hospital spiked after KKH opened the Children’s Lipid Centre, dedicated to managing the condition in children, in May 2024.

Before that, KKH had seen about five new cases of FH a year from 2009. From May to December 2024, there were 10 new cases.

This grew to about 25 new cases in 2025, said Professor Fabian Yap, KKH’s head and senior consultant of endocrinology service.

FH is a hereditary condition caused by mutations in genes, impacting the body’s ability to process cholesterol. Left untreated, it would lead to severe health issues.

Men are 20 times more likely to have heart disease between the ages of 20 and 40, may start to experience chest pain in their early 20s, and face a likelihood of suffering their first heart attack or stroke in their early 30s, said Prof Yap.

About half of men with FH are likely to have heart disease by the age of 50, and may experience a possibly fatal heart attack or stroke between their 40s and 60s.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, if FH is left untreated, heart attacks happen in 30 per cent of women by age 60, and in 50 per cent of men by age 50.

FH affects more than 35,000 people here, including 4,000 children and adolescents.

Yet over 90 per cent remain undiagnosed or do not receive timely treatment, especially those of a younger age, said KKH. For such cases, the first two years of their life are key for diagnosis and treatment.

In setting up the new centre, KKH aims to encourage early screening for children at risk of FH, and early management of the condition once identified.

A child’s diagnosis is also important as it can lead to doctors identifying and treating an affected parent or other family members, given that FH is a hereditary condition.

Patients with the genetic disorder have very high levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), also known as “bad cholesterol”, from a young age.

Without treatment, they would develop atherosclerosis, where fatty deposits build up and cause blockages and narrowing of the blood vessels, which would prematurely lead to cardiovascular diseases such as heart attacks and strokes.

Early diagnosis and early intervention with medication and diet changes before the fatty deposits start to build up in the blood vessels could greatly reduce the subsequent risks of diseases.

Prof Yap said that the average levels of LDL-C in children should be around 2.6 mmol/L (millimoles per litre). Those among the 0.1 per cent of children with the highest LDL-C levels have a reading of above 5.1 mmol/L.

In the most severe cases seen at KKH, the children had readings of more than 10 mmol/L.

They also had visible symptoms such as skin bumps or lumps at their elbow or Achilles tendon in the heel, which are caused by deposits of cholesterol.

Although a reading of more than 5 mmol/L would be highly suggestive of FH, genetic testing would help in confirming the diagnosis and knowing the exact gene mutations – certain mutations will lead to more aggressive and faster atherosclerosis, which warrants earlier interventions, said Prof Yap.

For instance, those with homozygous FH – meaning they inherited one gene copy from their father with a mutation, and another gene copy from their mother also with a mutation – will see far worse and more severe FH progression than those with heterozygous FH (having only one gene copy with a mutation from either parent).

Children with homozygous FH could have heart attacks as early as four or five years old.

Professor Fabian Yap, head and senior consultant of endocrinology service at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, encourages at-risk people to get tested and start treatment early.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

As part of the Ministry of Health’s efforts to enhance preventive care in Singapore

The first GAC, operated by SingHealth, opened at the National Heart Centre, and started accepting referrals on June 30, 2025.

Eligible Singaporeans and permanent residents with abnormally high cholesterol levels may be referred by their doctors to the GAC for drawing of blood for genetic testing at a subsidised rate. They will also undergo pre- and post-test genetic counselling.

Up to 70 per cent of the cost of these services will be subsidised.

Referred patients can expect to pay between $117 and $575 for the testing services. Those eligible for cascade screening – screening of first-degree family members after the index case has been identified – can expect to pay between $53 and $253 after subsidies.

Eligible patients can also tap MediSave to further offset the cost.

“We hope to encourage at-risk persons to get themselves tested, and reassure them that they do not need to be afraid of knowing whether they have FH,” said Prof Yap.

“FH patients can also lead a normal life and contribute meaningfully with proper treatment.”