Medical Mysteries

Rare genetic condition led to boy losing both kidneys at age 13

Medical Mysteries is a series that spotlights rare diseases or unusual conditions.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

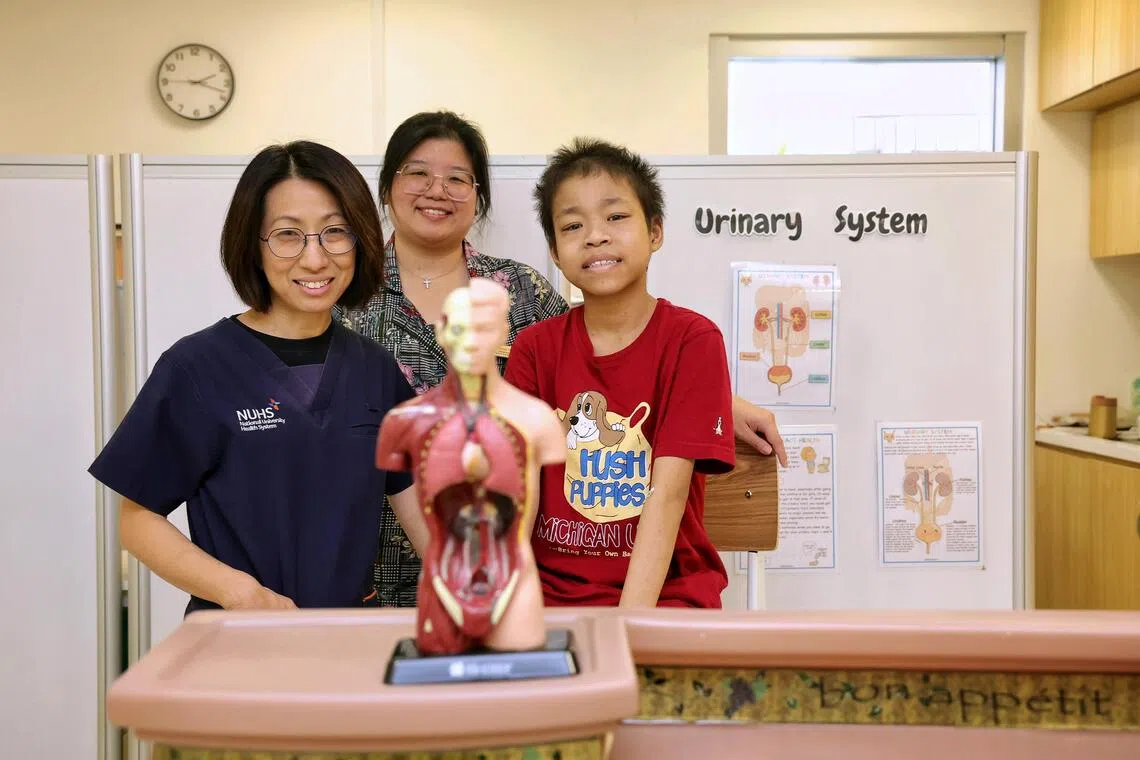

Au Wan Rong (right), 16, has a rare mutation that caused his kidneys to fail. With him are (left) Associate Professor Ng Kar Hui and medical social worker Cheng Peizhi.

ST PHOTO: KEVIN LIM

- At age 13, Au Wan Rong had both kidneys removed due to a rare TRPC6 mutation, a genetic condition causing kidney failure first noticed at age seven.

- Daily, Wan Rong manages his peritoneal dialysis independently. A kidney transplant offers the best hope, but he faces a long wait for a donor.

- TRPC6 mutation, discovered in 2005, is hereditary; Wan Rong copes with dietary restrictions and home dialysis while awaiting a kidney donor for a better life.

AI generated

SINGAPORE - Secondary school student Au Wan Rong was only 13 when he had both kidneys removed.

Today, the 16-year-old is on daily peritoneal dialysis, a home-based treatment for kidney failure that uses the lining of the abdomen as a natural filter to remove waste and excess fluid from the blood, which he administers himself “with great expertise”.

This involves draining the old fluid from his abdomen, filling it with new solution, and then sitting and waiting while the new solution collects waste and extra fluid. The process requires a strict sterile approach, including thoroughly washing one’s hands and carefully cleaning the connection area before each exchange to prevent infection.

“He is the youngest patient I have who does this on his own and does it cleanly without any infection,” said Associate Professor Ng Kar Hui, a senior consultant with the division of paediatric nephrology, dialysis and renal transplantation at the Khoo Teck Puat – National University Children’s Medical Institute’s department of paediatrics.

The TRPC6 protein is an important part of the cells in the kidney that help filter waste from the blood, and Wan Rong’s kidney failure was due to a TRPC6 mutation, a genetic condition often linked to a progressive kidney disease.

Prof Ng said the mutations can cause a “gain-of-function” effect, and this excessive activity causes the kidney’s filtering unit to leak protein, leading to swelling, fatigue and kidney failure.

Wan Rong was only seven when the condition surfaced.

His parents noticed his urine looked “foamy like soapy water and my face was also extremely swollen”, he told The Straits Times.

Wan Rong was rushed to the emergency room of KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital for urgent tests.

He went through a series of urgent clinic visits and hospitalisation before his parents were told to brace themselves for a serious kidney condition in their middle child.

The exact cause of his renal failure was unknown at the time.

Doctors then thought what Wan Rong had was run-of-the-mill kidney disease and treated the condition with steroids to reduce inflammation. Kidney disease in children can result from birth defects, genetic disorders like polycystic kidney disease and urinary tract issues such as blockages.

The steroids did not work as Wan Rong’s condition progressed, and he was transferred about a year later to the National University Hospital, which has the only dedicated chronic dialysis service for children.

“(The medication) became toxic when his body did not respond to it and his kidneys deteriorated rather quickly. We were running research programmes on genetics then on patients who were not responding to treatment. We found that between 10 and 15 per cent of patients with kidney conditions were genetic cases and that was why Wan Rong was tested,” Prof Ng said.

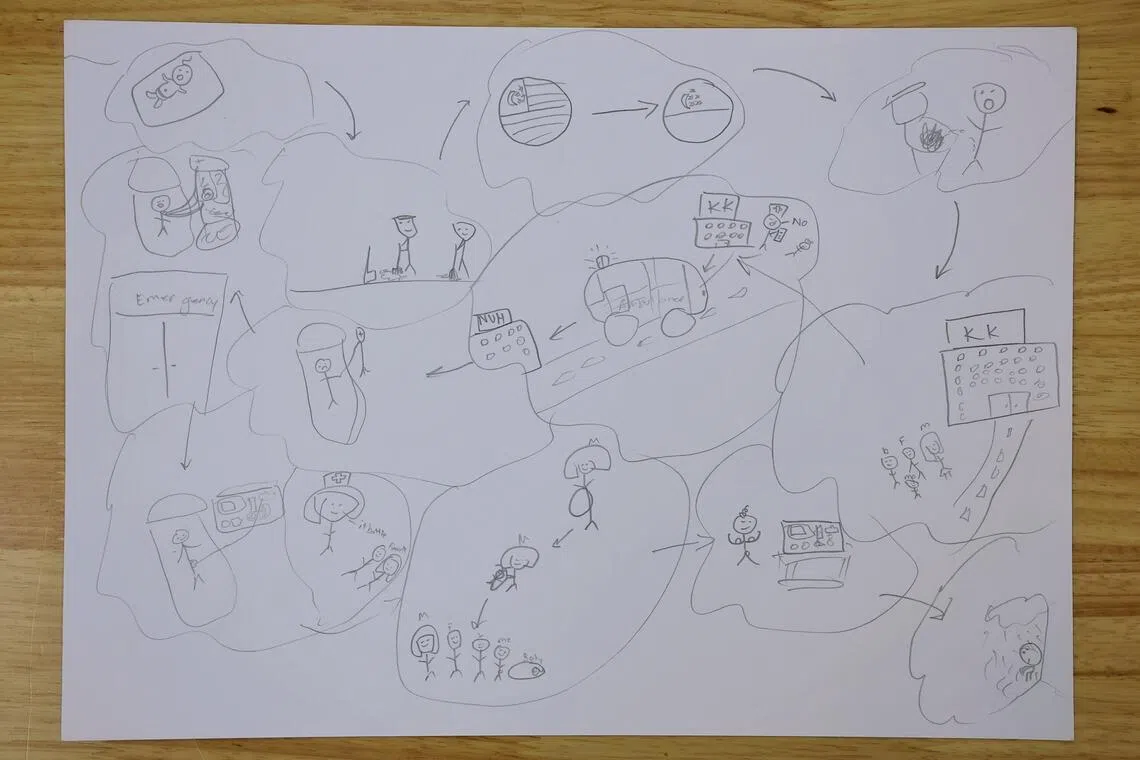

Au Wan Rong’s depiction of his medical journey through art. It was an examination piece for Secondary 3, and medical social worker Cheng Peizhi kept it with his medical records.

ST PHOTO: KEVIN LIM

It was then that Wan Rong was found to have the rare TRPC6 mutation, which is hereditary. This means that if one parent carries the mutation, there is a 50 per cent chance of passing the altered gene to each of their children. But some mutations are spontaneous and are not inherited from parents, Prof Ng said.

TRPC6 mutation was discovered only in 2005 and its exact prevalence is still unknown.

Surviving with no kidneys

Wan Rong said that despite having to go for dialysis and steroid treatments to manage his condition, he was still running around, playing catch with his primary schoolmates and living an otherwise normal childhood. But when he turned 13, his condition became serious.

“There was an excruciating pain in both my legs and I was hospitalised so that the doctors could get to the bottom of the cause. I ended up having both my kidneys removed because of the waste build-up and infections,” he said.

After losing both his kidneys, he developed bad headaches and “lived in the hospital for a long time, missing school”, he said.

The headaches were caused by his fluctuating blood pressure, and both were controlled with medication.

With the removal of both kidneys, Wan Rong’s diet needs to be highly restrictive to manage waste products and fluids, and he has to adhere strictly to a kidney-friendly plan to manage his dialysis. Among other things, he has to severely limit his fluid intake to prevent severe fluid overload, high blood pressure and heart failure.

Due to his condition and the fact that he was constantly in and out of hospital, he did not have the opportunity to get to know his classmates well, but Wan Rong did develop a special relationship with his medical social worker, Ms Cheng Peizhi.

She took over his case in 2020 from another medical social worker and admitted that she took some time to win him over.

“I see him almost once a month or sometimes more, and he often comes looking for me when he is here. We also worked through a pilot rewards programme to help him be more adherent to medication and treatment when he was very unmotivated and dejected,” she said.

Wan Rong also admitted that he was bullied in secondary school, “but it was not outwardly intrusive”. He told ST he has only one close friend at school, who also has a health condition.

“It causes him to black out and bleed from his nose. Both of us bonded over our illnesses and at times we would talk for hours after school and share our ideals, our future,” he said.

While his friend has plans to become a chef and is laying the foundation by learning to cook and bake at the Institute of Technical Education, Wan Rong declined to talk about his future.

For TRPC6 kidney disease, a donor transplant is possibly the most effective treatment option, offering him a chance at a normal life. This is because the genetic mutation is in Wan Rong’s native cells, not in the donor kidney.

However, the waiting list for a dead donor is long.

“I have been waiting for the last eight years and there had been false alarms, resulting in disappointments,” he said.

The average waiting time for a dead donor kidney transplant in Singapore is about eight to 10 years, but this can vary amid the high demand for organs and limited availability of dead donors.

The wait can be significantly shortened with a living donor transplant, which can be done, on average, about six months after donor and recipient assessments are complete.

As this is a hereditary condition, there are no suitable blood-related living donors for Wan Rong, and his hope would be for an altruistic donor.

Both Wan Rong and his parents have learnt to take things “as they come”. “Until I find a kidney donor, I can only live my best life a day at a time,” he said.

If you would like to be a living altruistic donor, contact a transplant hospital to find out about its donation programme.