From slathering mud to eating strange roots, people have tried different ways to stay young, but an experiment on mice involving faecal matter is giving hope that humans may slow down the ageing process while tackling conditions such as dementia.

Doctors have known for some time that faecal matter is a window to the trillions of good and bad bacteria, viruses and fungi living in the intestines, collectively known as the gut microbiome.

What a layman may describe as a poo transplant - taking faecal bacteria from donors, processing them and inserting them into the patient's gut either orally or through a colonoscopy - has been used to successfully treat Clostridium difficile infection, which causes recurrent severe diarrhoea and colon inflammation.

The transplanted faecal matter restores the patient's gut microbiome by introducing healthy bacteria.

Beyond keeping the gut healthy, the microbiome is known to impact the brain as well. Although they are far away from each other, the stomach and the brain have a two-way communication known as the brain-gut axis.

Now, scientists in Europe have found that faecal matter is hiding clues related to ageing and cognition.

When the scientists transplanted faecal matter from old mice into young mice, the younger ones faced problems related to memory and navigation.

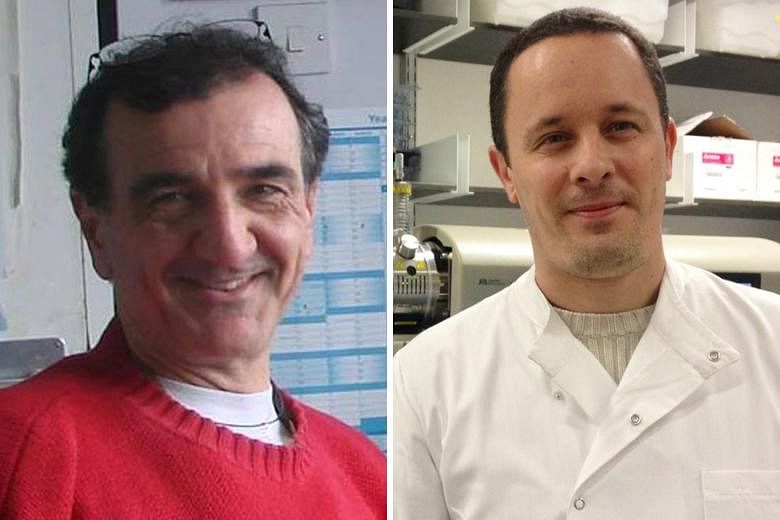

"In short, the young mice began to behave like older mice," said a co-lead of the research, Dr David Vauzour, who is senior research fellow at the University of East Anglia in Britain.

The members of the research team are mainly from his university, the University of Florence in Italy, and the Quadram Institute in Britain.

In the navigation test, the young transplant recipients were found to be slower.

They took about 41 seconds to find and enter the correct hole that led to a cage, while mice from two control groups took 30 and 23 seconds respectively.

In the memory test, the mice were given a set of familiar and new objects. Being inquisitive creatures, they should spend more time fiddling with the new object.

But the transplant recipients were not that interested in the new object, compared with those in the control groups.

The scientists then opened up their brains, zeroing in on the hippocampus, the region that plays a vital role in learning and memory.

They found that the proteins that were expressed in the brains of the mice which underwent transplantation were different from that of the control group.

For one thing, the tangled tau protein, which is prevalent in those with Alzheimer's disease, saw an uptick in the young mice, said Dr Vauzour.

The study was published in the journal Microbiome last month.

The research's other co-lead, Associate Professor Claudio Nicoletti of the University of Florence, said: "This work provides a strong rationale to devise therapies aiming to restore a young-like microbiome to improve cognitive functions and quality of life in the elderly."

Commenting on the findings, Dr Jeremy Lim, chief executive and co-founder of the Asian Microbiome Library in Singapore, said: "If the science is consistent in humans, it may open the door to modifying the gut microbiome to treat dementia and other brain health conditions."

The European team is now studying older mice transplanted with the faecal matter of young mice.

The team is also discussing with a centre in the Netherlands about similar research with primates.

Dr Nicoletti said: "If you improve cognition or other functions in old monkeys, chances are you can do the same in humans.

"If we see very positive results in the current mice study, we can start clinical trials on humans within two years."