From crisis to comeback: How The Straits Times reported Singapore’s economic ups and downs

The paper has chronicled economic realities. Post-independence, five turbulent periods tested the nation’s resilience.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The Straits Times has chronicled Singapore’s economic highs and lows, capturing pivotal moments with immediacy, insight – and even foresight.

PHOTOS: ISTOCKPHOTO

Sometimes, a newspaper article can offer a rich and nuanced understanding of a past era that can’t quite be captured by a history book.

The Straits Times, Singapore’s paper of record since 1845, has chronicled the country’s economic highs and lows, capturing pivotal moments with immediacy, insight – and even foresight.

Take a brief article titled “Malayan trade in 1930”, published on March 13, 1931. Though short, the report offers important clues to the impact of the Great Depression on British Malaya and, by extension, Singapore.

The article highlighted how the global downturn, which began in 1929, severely affected the two mainstays of Malayan trade: tin and rubber. Even opium, then still legally traded, was declining as a revenue source.

The piece noted that the nascent palm-oil industry could serve as a “third string” to reduce economic over-reliance on tin and rubber, a hint of the concept of diversification, which would later become a policy mantra for independent Singapore’s economic planners.

An article, titled “Malayan trade in 1930”, published in The Straits Times on March 13, 1931.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The writer also looked to Singapore for industrial promise, noting its “illimitable supplies of cheap labour from east and west – China and India”, and the slow but steady emergence of a manufacturing base.

The Great Depression, which ended with the onset of World War II, marked the beginning of the end of British global economic dominance. By the end of the war, the United States had emerged as the pre-eminent global power.

Singapore, gaining independence in 1965, began a dramatic industrial transformation. Manufacturing took the lead over commodity trade, and the paper continued to document the journey of modern Singapore’s economy, through its triumphs and turbulence alike.

Here are five key moments:

Independent Singapore’s first recession (1985)

In the two decades following independence, Singapore focused on rapid industrialisation through export-led growth. Foreign investment and labour-intensive manufacturing helped reduce unemployment and raise incomes.

But by 1985, its first post-independence economic recession loomed, triggered by external economic headwinds and internal structural weaknesses.

Early warnings came from then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. In his New Year message on Jan 1, 1985, he cautioned about slowing growth in the US, Japan and Europe and warned of knock-on effects across Asean and developing economies.

Among other things, the developed economies had crushed their own economic growth by raising interest rates sharply to control runaway energy prices caused by the 1979 revolution in Iran, a major oil exporter. This led to a drop in global demand, hitting Singapore’s export-dependent economy hard.

At home, Singapore was grappling with rising business costs after two decades of rapid growth. The construction sector, which had boomed in the early 1980s, also began to contract as projects slowed and oversupply loomed.

In March 1985, then Minister for Trade and Industry Tony Tan announced the formation of an Economic Committee, led by then Minister of State for Defence and Trade and Industry Lee Hsien Loong, to study the causes of the downturn and map out recovery strategies.

It became clear that unprecedented measures were needed to shore up the economy. The most controversial proposal was to sharply cut employers’ Central Provident Fund (CPF) contributions from 25 per cent to 10 per cent. The aim was to reduce business costs and restore competitiveness.

The proposed cut led to heated parliamentary debates. Even among People’s Action Party MPs, views were divided. Public reaction was equally intense. The Straits Times published letters from readers on both sides of the argument.

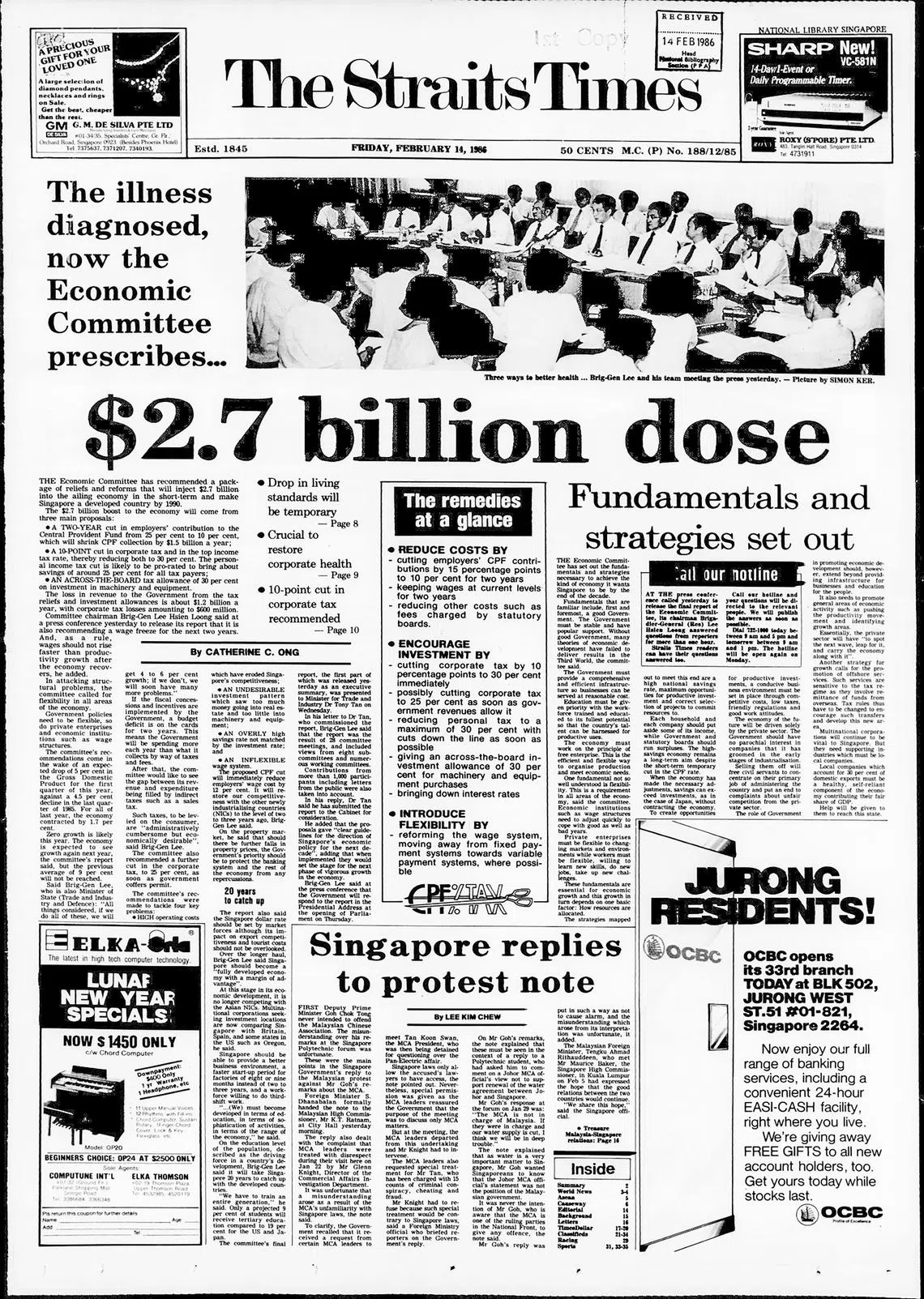

The Economic Committee’s report in February 1986 recommended a package of reliefs and reforms that would inject $2.7 billion into the ailing economy and make Singapore a developed country by 1990.

The boost came from measures including the proposed two-year cut in employers’ CPF contribution, and a 10-point cut in corporate tax and the top income tax rate.

On Feb 14, 1986, ST reported on the Economic Committee recommending a package of reliefs and reforms to boost Singapore’s economy.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The committee also said flexibility was needed in all areas of the economy, including government policies and wage structures.

“The effect of these cost-cutting measures will be a temporary drop in the standard of living of Singaporeans,” the report said. “This is unpalatable but inevitable. It is the only way companies can regain their profitability, so that Singapore can prosper and our incomes rise again.”

The recession also triggered a major corporate failure in Singapore.

In November 1985, Pan-Electric Industries, a conglomerate involved in marine salvage, hotels and property, went bankrupt with massive unpaid debts. It sent shockwaves through Singapore’s stock market and financial sector.

Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s New Year message in 1986 laid bare the toll: rising unemployment, falling exports and a general sense of uncertainty.

But from the crisis came structural reforms that strengthened the economy down the road, including wage flexibility, productivity drives and a shift towards higher value-added industries.

Asian financial crisis (1997 to 1998)

Singapore’s economy rebounded strongly after the 1985 crisis, growing steadily through the early 1990s. But in 1997, a storm swept through Asia’s financial markets, sparked by the collapse of the Thai baht on July 2.

Thailand’s decision to float the baht set off a chain reaction across the region. One headline read: “Floating baht seen as a devaluation”.

In an editorial, the paper asked: “What else can a beleaguered government do when the economy threatens to seize up with falling exports, massive debts, a growing trade deficit and its currency under relentless speculative attack?”

The Singapore dollar was able to avoid a massive decline, thanks to the central bank’s policy of managing it against a basket of currencies rather than pegged to the US dollar, as Thailand had been doing before floating the baht.

But by the second half of 1998, regional contagion had dragged Singapore into recession. Gross domestic product (GDP) shrank by 2.2 per cent for the year.

“Singapore in recession”, read the front-page headline on Nov 11, 1998.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Singapore’s flexible exchange rate mechanism helped maintain its export competitiveness, resulting in an economic rebound in 1999 led by the manufacturing sector. The recovery was sustained through the year and overall GDP for 1999 grew by 5.7 per cent.

The Government also helped by announcing off-Budget measures in June 1998 that were worth $2 billion, aimed at reducing business costs.

Dot.com crash and recession (2001)

The burst of the dot.com bubble in 2000 marked the end of an era of exuberance in global technology stocks. Over the next two years, trillions of dollars in market value were wiped out. Singapore, heavily reliant on electronics manufacturing and global trade, was not spared.

A March 14, 2000, front-page article noted: “Sentiments were unnerved by the knocking suffered by technology stocks whose meteoric rise in recent months had seemed unstoppable.”

The Singapore economy contracted by 1.1 per cent in 2001, a sharp reversal from the 9 per cent growth in 2000. This was exacerbated by the Sept 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the US which rattled global markets, curbed consumer confidence and slowed down travel and investment.

Singapore’s downturn was thankfully brief, but it marked another turning point: a further diversification in sources of economic growth by shifting towards services, financial resilience and innovation-driven growth.

Global financial crisis (2007 to 2009)

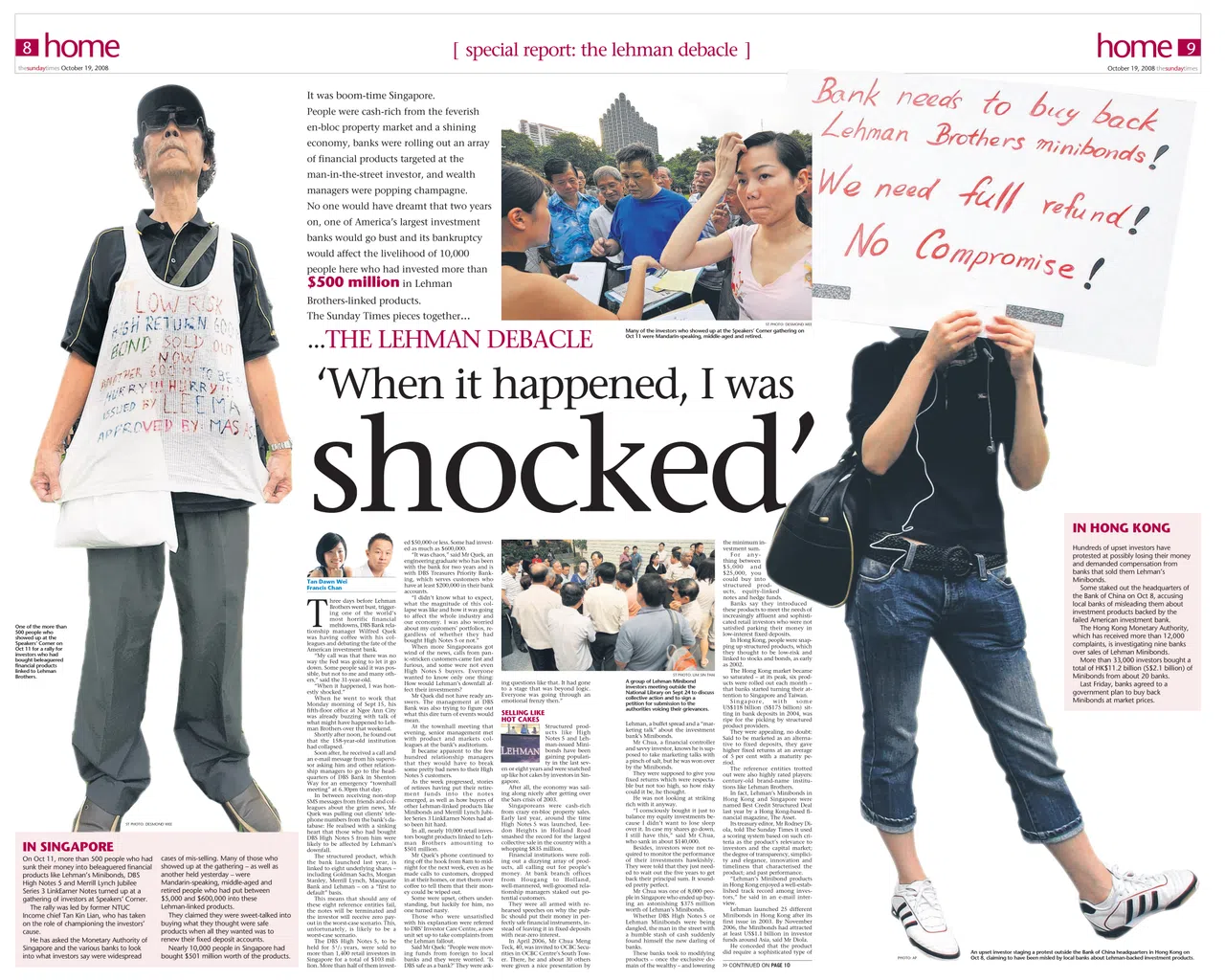

The financial crisis began with the collapse of sub-prime mortgage markets in the US and quickly escalated into a global credit crunch following the bankruptcy of investment bank Lehman Brothers on Sept 15, 2008.

Although Singapore’s banks had limited direct exposure to US sub-prime assets, the global freeze in lending and plummeting demand for exports hit the economy hard. In the fourth quarter of 2008, Singapore’s GDP shrank on a seasonally adjusted basis by 2.3 per cent quarter on quarter, followed by a 2.6 per cent contraction in the first quarter of 2009.

Public anger erupted when thousands of consumers lost their savings in complex investment products linked to Lehman Brothers, such as Minibonds and High Notes 5. About 10,000 retail investors, including the elderly and less educated, lost over $500 million in products sold by financial institutions here.

On Oct 11, 2008, more than 500 angry investors turned up at the Speakers’ Corner in Hong Lim Park. Several such protests were held every Saturday in the weeks to follow. The Straits Times reported on these extensively.

A special report in the paper on Oct 19, 2008, about the Lehman Brothers debacle.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The Government launched investigations, which led to penalties for 10 financial institutions, and tighter industry supervision.

The Government also pledged $2.9 billion in November 2008, followed by a massive $20.5 billion Resilience Package in January 2009. For the first time in history, Singapore dipped into its national reserves, drawing $4.9 billion to support the economy and jobs. In the end, it needed $4 billion, and was able to return the full amount into the reserves by the end of its term in 2011.

The Singapore economy weathered the financial storm better than feared. In August 2009, then Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said that “the worst is over for the Singapore economy” and that “the eye of the storm has passed”. In November 2009, the Ministry of Trade and Industry declared that the recession was effectively over.

Covid-19 pandemic (2020)

The Covid-19 pandemic led to Singapore’s worst recession since independence, with the economy contracting by 3.8 per cent in 2020. The “circuit breaker” period from April to June 2020 severely impacted the food and beverage, retail and travel sectors.

The Government responded with a series of stimulus packages totalling nearly $100 billion, or about 20 per cent of GDP. This included a Jobs Support Scheme

For the second time in history, Singapore tapped its national reserves. The Government drew about $40 billion from past reserves for Covid-19 response measures across financial years 2020 to 2022.

By late 2021, with high vaccination rates and phased reopening, Singapore’s economy began to recover. The rebound was uneven, but GDP grew by 9.8 per cent that year.

Ovais Subhani is senior business correspondent, joining The Straits Times in 2019. He was Asia treasury correspondent with Reuters, covering the region’s currency and bond markets, and was also news editor at Bloomberg’s world commodities desk.