Fish, crop kings and a fleet that never arrived: Five stories from Chencharu in Yishun

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

An artist’s impression of a new park in Chencharu incorporating an existing bungalow atop a small hill.

PHOTO: HDB

SINGAPORE – The masterplan for the forthcoming Chencharu housing estate

The Straits Times follows the trail back into the area’s lush history.

1. What’s in a name?

News of the development sparked curiosity among some about its “unusual” name, though its namesake – the street known as Lorong Chencharu – is more obscure than wacky.

Forking out from the longer Sembawang Road, Lorong Chencharu is a rare surviving rural road from the 20th-century Bah Soon Pah village that once occupied the Chencharu plot, according to maps from the early 1970s.

Its sister streets – Lorong Cherdek, Lorong Mayang, Lorong Mayang Kechil and Lorong Akar – were effaced in the 1980s, after urbanisation began in earnest post-1976.

Chencharu is the outmoded Malay word for horse mackerel, according to the Malay-English dictionary of colonial administrator Richard James Wilkinson. These days, the palm-sized fish is more likely to go by “selar”.

The old street will soon run through the new estate, quietly evoking the fisheries fed by the erstwhile village’s low-lying swamps.

Not all is lost. A touch of seafaring flavour is preserved in latter-day Lorong Chencharu – home to a string of aquariums that easily recall the indigenous Orang Seletar, who once docked their boats in those parts.

2. King of the hill

Claiming pride of place at the planned new park in Chencharu is a weathered bungalow cresting a grassy knoll, where it has stood for more than 100 years.

The tricoloured house at 50 Bah Soon Pah Road is a relic of Singapore’s once-booming rubber industry and was built by the Bukit Sembawang Rubber Company in 1912 to house the surrounding rubber estate’s manager or assistant manager, according to the National Heritage Board’s (NHB) Roots portal.

The building, which the authorities have pledged to preserve, has floors raised above ground on masonry piers and columns, as if on stilts. This would have cooled the interior in the otherwise muggy plantation.

The bungalow at 50 Bah Soon Pah Road sitting undisturbed as earth works were carried out in 2022.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The design of Chencharu’s first Build-To-Order flats will pay homage to this landmark, with a similar red, black and white colour scheme for the blocks’ facade.

A black stripe around the bottom few floors will mark the bungalow’s elevation above ground.

3. Bah Soon Pah

The proud house is a window to its namesake, Bah Soon Pah, a moniker of Lim Nee Soon – the Straits-born Chinese industrialist remembered as the pineapple king and rubber king.

Lim was the first general manager of the once-titanic Bukit Sembawang Rubber Company.

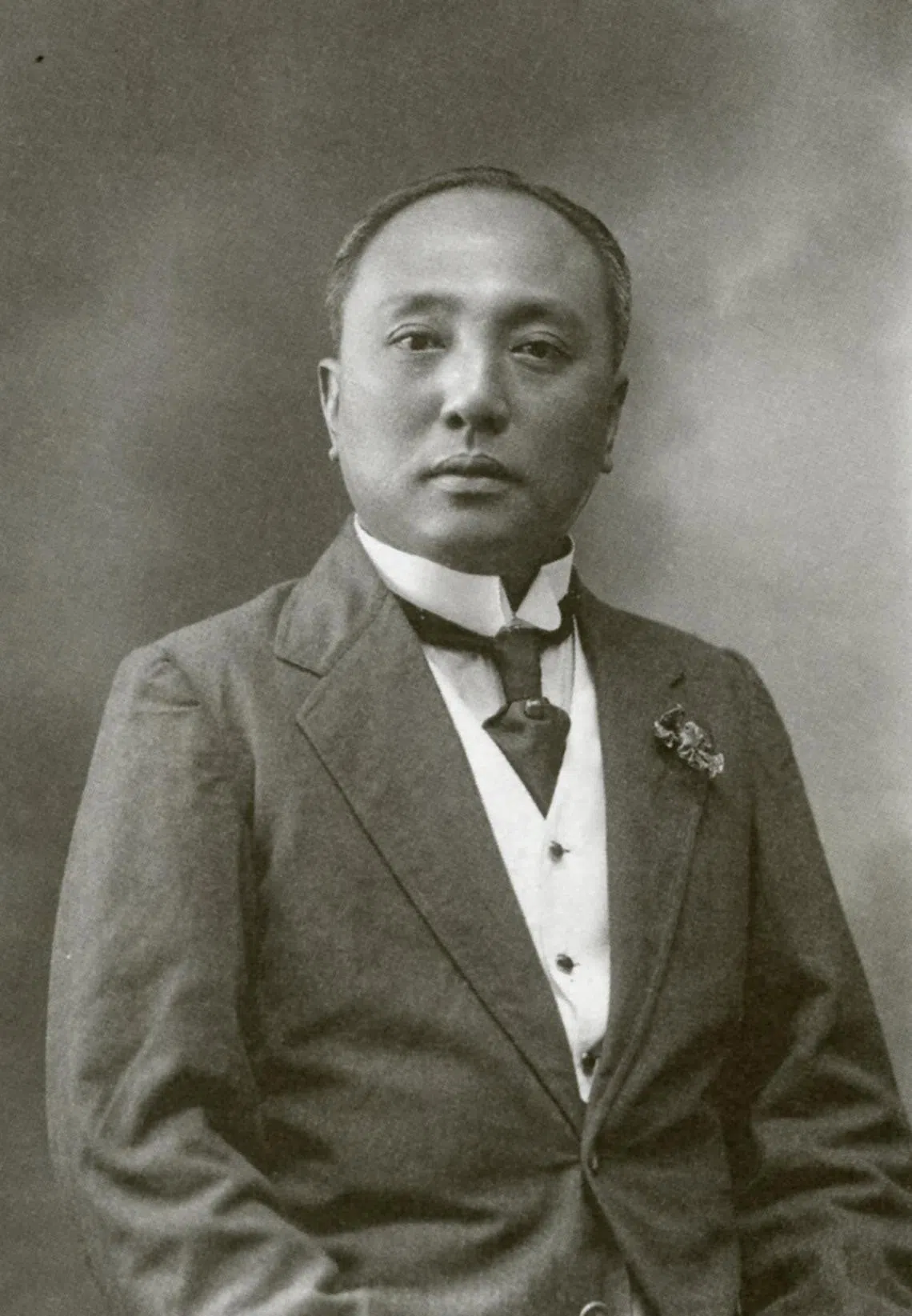

Singapore pioneer Lim Nee Soon was a pineapple plantation king and rubber magnate.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF SUN YAT SEN NANYANG MEMORIAL HALL

He built an agrarian empire that measured over 4,000ha at its peak and is credited with effectively developing Yishun into a settlement as new immigrants came to work his fields.

Outside of business, Lim was known as a kindly landlord and an active community leader.

During the Singapore Mutiny in 1915, he persuaded six mutineers to surrender peacefully.

In 1918, he was made a Justice of the Peace, and he later co-founded the first Chinese secondary school in Singapore, The Chinese High School, now known as Hwa Chong Institution after its merger with Hwa Chong Junior College.

He was a close friend of the revolutionary leader and first president of the Republic of China, Sun Yat Sen.

When Lim died in Shanghai in 1936, aged 57, he was given a state funeral by the Nanking government and laid to rest near Sun’s mausoleum.

Lim has lent his or his family’s names to at least 18 places in Singapore, most prominently Yishun, which is the pinyin rendering of his name Nee Soon.

Bah Soon Pah is believed to be an amalgamation of “Baba”, the salutation for Peranakan men; “Soon”, taken from Lim’s given name; and “Pah”, which means “rural plantation” in Hokkien, according to the local toponymics book, What’s In The Name? How The Streets And Villages In Singapore Got Their Names, by Mr Ng Yew Peng.

4. The land remembers

Lim’s fortunes tell a good part of Singapore’s agricultural story.

Well before his first ventures in the early 1900s, 19th-century Yishun was already cultivated land, though what sprouted was gambier and pepper.

Gambier extract was used to make leather-softening agents until a synthetic equivalent was developed. The tracts that had crowned the first gambier king, Seah Eu Chin, rapidly vanished and by 1866 the industry was culled.

Rubber and pineapple – which are complementary in cropping – would rise in its place, quite literally taking over the old gambier lands in Yishun.

Vegetable farming in Nee Soon in the 1950s.

PHOTO: ST FILE

After the first rubber seeds were brought in from South America and the first rubber tree planted in the Singapore Botanic Gardens, H.N. Ridley, the director of the Botanic Gardens in 1888, shared his improved rubber-tapping method with Chinese merchants – ushering in a new crop of kings.

The local rubber magnates would catch the wave of global demand for the material after the car tyre was invented in the early 20th century.

That, too, subsided after World War II, when a synthetic alternative was invented and, by the early 1950s, local rubber plantations had disappeared.

Today, rubber trees continue to flourish in Yishun Park, according to NHB’s Roots portal.

5. Sembawang Naval Base

Chencharu also houses Naval Base Secondary School, a transplant from the old British naval base, where the school was set up for the children of navy employees.

Sections of rubber plantations, as well as some villagers and most of the Orang Seletar, were “cleared” to make way for the base, which opened in 1938 and boasted the world’s largest dry dock at the time, measuring 305m.

According to the Roots portal, its girth was designed to fit the Royal Navy’s largest battleships, though a fleet never materialised.

Britain’s defence plan had been to dispatch its ships from Europe to dock in Singapore in the event of a seaborne attack by the Japanese. This quickly fell apart after World War II broke out in Europe and the fleet was diverted to battle Germany.

Instead, a small naval squadron known as Force Z was dispatched to distract the Japanese forces in 1941. The Japanese sunk the contingent from the air.

Without a fleet, the naval base was indefensible. As the Japanese army congregated across the Johor Strait, the British decided to wreck the docks and destroy their equipment to prevent these from falling into enemy hands, said the Roots portal.

By January 1942, the British had evacuated the base.