Farmers face hurdles in push to innovate and boost Singapore’s food security

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Former Kranji Countryside Association president Kenny Eng feels that working with food-processing companies is the way forward.

ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

SINGAPORE – Warm up a packet of assam mullet chowder for a quick dinner after work, or simply dig into a tub of kale and coconut gelato.

These are some fuss-free meals or quick snacks made from farm-fresh products in Singapore.

Former Kranji Countryside Association president Kenny Eng, 49, said farmers here are serious about treating the industry “not just as an economic engine but also one with potential for innovation and lifestyle transformation”.

“We adopt this new approach – one that has a more rounded development trajectory – so that the local agricultural industry remains relevant in the future,” he added.

According to the inaugural Singapore Food Statistics report released in April 2022, there are an estimated 260 land- and sea-based farms here.

The Government has set its “30 by 30” goal of ensuring that 30 per cent of local food needs can be met from domestic production by 2030.

A masterplan has been rolled out to turn Lim Chu Kang into a high-tech, sprawling district producing leafy vegetables, mushrooms and fish in a climate-resilient, energy-efficient way.

Some options include a “stacked farm approach” to intensify land use, growing produce in underground caverns to guard against rising sea levels, and using solar panels in greenhouses to harness renewable energy.

Mr Eng, who is director of horticultural business at Nyee Phoe Group, feels that working with food-processing companies is the way forward. Its own Gardenasia brand has come up with The Local Farm’s (TLF) range of ready-to-eat and ready-to-cook products made with fresh produce from farms here.

TLF by Gardenasia has also created a platform to engage change-makers and thought leaders to challenge mindsets and explore various perspectives on important issues that impact the local farming community, Mr Eng added.

“Products like Egg Story’s Dashimaki Tamago, The Soup Spoon’s Assam Mullet Fish Chowder and Papitto Gelato include flavours such as arugula oat, kale coconut, pineapple baby spinach and even round spinach, which add value to farmers’ efforts, while at the same time make it easier for consumers to support local producers,” he said, noting the offerings from other industry players.

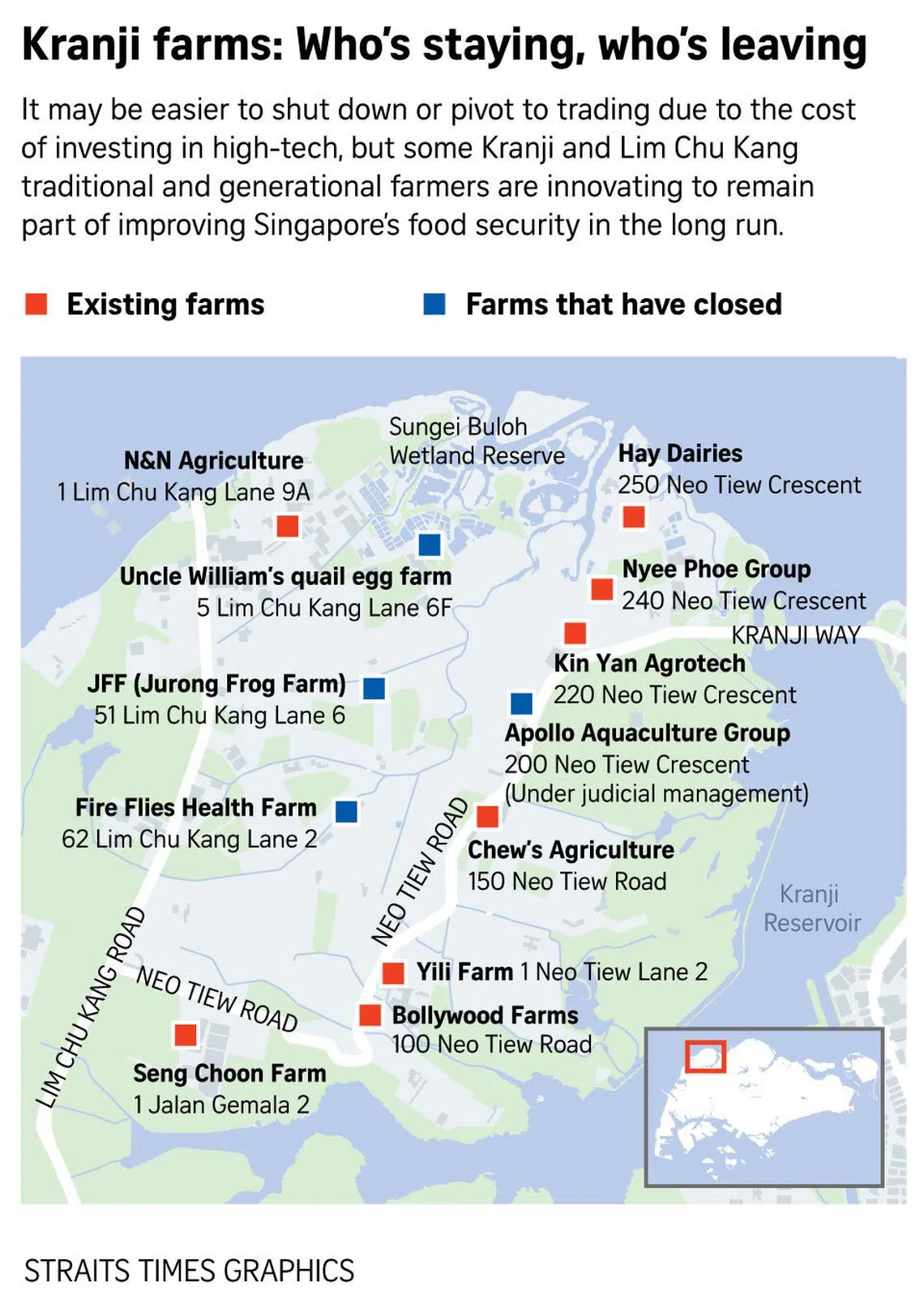

Still, the road to a higher-tech food industry is not a smooth one, amid other competing needs for land, and there have been dropouts, with Mr Eng warning that “if there are no farmers, there is no food”.

Several farmers, some of whom have families that have been in the trade for generations in Lim Chu Kang and Kranji, for between 25 and 70 years, have quit.

Some had to return land that was slated for military use, while others bowed out, conceding to high-tech, highly productive and resource-efficient farms.

Fire Flies Health Farm

Uncle William quail farm, one of the oldest in Singapore, called it a day in July 2023 after 69 years in the business.

It was started by the late Mr Ho Seng Choon, and his son, Mr William Ho, 57, failed to secure either of the two land parcels in Lim Chu Kang awarded in 2018 by the then Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority to continue the business. Its original site was taken over for military use.

Mr William Ho declined to be interviewed for this article.

Singapore’s only heritage frog farm, Jurong Frog Farm, shut on Feb 1, 2023, with the land returned for military use. Home to more than 15,000 frogs, the family business was started in 1981.

Jurong Frog Farm used to be home to more than 15,000 frogs and a place where children learn more about frogs. It closed in February 2023.

ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

Switching to a new site and a different operating model did not appeal to its director and second-generation farmer, Ms Chelsea Wan, 39. “We could have partnered other farms such as Qianhu or Bollywood to continue (as a farm) but I didn’t want to grow frogs or run an abbatoir any more,” she said.

Ms Wan has instead turned to trading, going into joint ventures with other industry veterans in the region to provide her with frog meat and retaining her online store.

In October 2021, the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) said about 390ha of the land in Lim Chu Kang would be redeveloped under a masterplan to create a “high-tech, highly productive and resource-efficient agri-food cluster”. Together with other efforts, such as tapping more sources for food imports, it would create a buffer against global supply shocks.

SFA said then that a high-tech vegetable farm has the potential to yield more than 1,000 tonnes of produce per hectare every year, compared with 130 tonnes of vegetables per hectare every year from an average farm which occupies around 2ha of land.

Like Ms Wan, Mr Eng feels that reinvention is necessary in an industry facing diminishing margins and rising costs and risks. Still, going high-tech could mean traditional farms need to pour as much as $4 million into new equipment and factory space – about four times the estimated cost of relocating to a different site but still using the old ways.

“But reinvention has more to do with human ingenuity, resilience and creativity than just having technology silver bullets,” said Mr Eng, a fourth-generation farmer at Nyee Phoe.

He cites the example of an eight-storey fish farm in Lim Chu Kang – the tallest in Singapore and the region – by home-grown company Apollo Aquaculture Group.

It was built amid a governmental push to get farmers here to use technology to improve yields and was slated to start operations in the first quarter of 2021, and achieve annual output of 2,700 tonnes of fish by 2023.

It had promised that its first phase of operations, which involved farming mainly hybrid grouper and coral trout in the first three storeys of the building, was expected to supply up to 1,000 tonnes of fish a year. This was more than six times the yearly output of 150 tonnes from Apollo’s three-tiered pilot farm in Lim Chu Kang.

But Apollo, according to a filing with the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority in February 2023, went into judicial management. And the $65 million multi-storey facility in Neo Tiew Crescent now sits unused.

Apart from its eight-storey high-tech fish farm, Apollo Aquarium at 36 Lim Chu Kang Lane 5A looks to have closed.

ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

A Feb 5, 2023, Business Times report said judicial managers of Apollo Aquaculture Group were in talks with some investors to rehabilitate the group, and its operating subsidiary, Apollo Aquarium, is not under any form of administration.

Mr Eng said for a small market that imports 90 per cent of its food, Singapore’s food supply can be threatened by climate change and geopolitical uncertainties, and technology can be just one answer.

“But putting all our eggs in the high-tech basket is never the answer, and should farmers take a wait-and-see approach, it is likely that more farms will shut for good. This means that in 50 years, the social ecosystem of farms in the present Kranji countryside would be gone. Rebuilding it organically would also be close to impossible,” he added.

Mr Eng said the issue with agricultural technologies has always been its underlying business factors. “There were high risks, lack of financing and limited farm tenures that held us back. As production capabilities are inseparably linked to business prospects, the farm transformation map may be asking farmers to fly before they can even walk,” he noted.

He added that while a key strategy to overcome space constraints lies with tapping technology, using resources more efficiently and developing a generation of agri-specialists, “more can be done to connect the dots of a natural and social ecosystem and more holistically develop the agricultural sector”.

As for the plan to boost Singapore’s production of its own food to 30 per cent by 2030, Mr Eng said: “It was and has always been a goal set by the Government. As farmers, we need to band together and work as a community to come up with a solution to meet this goal.”

Nyee Phoe Group, together with the farming community, is up for the challenge.

“The local farm believes in bringing convenience of accessing locally harvested produce to the people, and we understand the consumer pain point of having to go out of their way to find and support locally grown produce. With the ready-to-cook, ready-to-eat lines, we work with Singapore farms to provide consumers a fun and easy way of supporting local farms by buying local,” he said.