Europe’s pathfinding cross-border carbon capture project on track for launch

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The $1.7b Northern Lights joint venture, touted as Europe’s first cross-border industrial carbon capture and storage (CCS), has caught the world’s attention.

PHOTO: NORTHERN LIGHTS

BERGEN, Norway – On a cold, blustery island in Norway’s North Sea lies a trailblazer project aimed at fighting back against climate change.

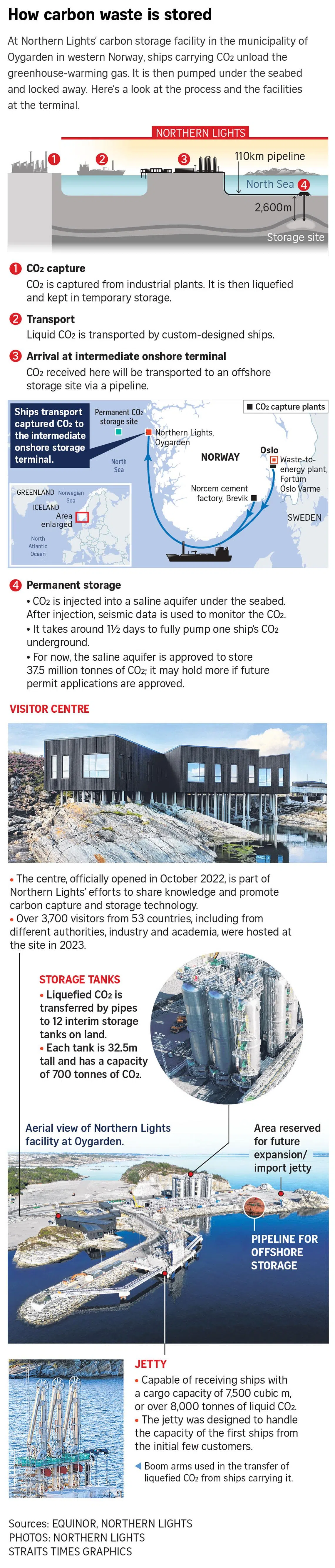

By burying planet-warming carbon dioxide (CO2) generated by European industrial companies in the depths under the seabed, it hopes to help several hard-to-abate industrial sectors decarbonise.

The $1.7 billion Northern Lights joint venture, touted as Europe’s first cross-border industrial carbon capture and storage (CCS) project, has caught the world’s attention, like its auroral namesake.

The Straits Times toured the Northern Lights receiving terminal in the municipality of Oygarden in western Norway in June, along with a delegation of Singaporean companies, academics and government representatives.

The trip was organised by Norway’s trade representative Innovation Norway and the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Singapore.

Northern Lights’ director of communications and governmental affairs Benedicte Staalesen said construction at the Northern Lights facilities broke ground around December 2020, and is now 98 per cent complete.

The project is on track to receive CO2 in the fourth quarter of 2024, with a storage capacity of up to 1.5 million tonnes of CO2 per year, with an aim to expand to five million tonnes of CO2 per year eventually.

Northern Lights is owned by a trio of oil giants – Equinor, Shell and TotalEnergies – and spearheaded by the Norwegian government, with it footing 80 per cent of the bill for the first stage of development.

In exchange, the project will not charge two emitters, a cement factory and a waste-to-energy plant in Oslo, for storage of CO2 during phase 1 of the project.

Subsequent expansion of the project will be shaped by commercial demand, and phase 2 of the project already has two clients confirmed.

Carbon capture projects used to be met with raised eyebrows as it is technologically and economically unproven at scale, with multiple concerns including around whether CO2 can be captured and stored permanently.

But more are warming to the idea, with increased investment and policy support, and recognition of its necessity after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change affirmed in 2022 that CCS is critical for mitigating climate change.

When Northern Lights is operational, specialised ships will transport liquefied CO2 from emitters to the receiving terminal. The CO2 is then injected into a geological formation about 2,600m below the seabed.

Commenting on the testing that is being done to ensure carbon can be received and stored successfully, Ms Staalesen said: “There is a process to ensure facilities are built according to design, followed by a commissioning programme to ensure the facilities work according to design objectives. We are in the commissioning phase now.”

On how Northern Lights will ensure that stored CO2 does not leak, Ms Staalesen said that the underground storage complex consists of sand reservoirs and a sealing layer of caprock. The CO2 will be injected into a porous space filled with salt water in the rock formation, where it will be trapped.

“These are the same mechanisms that have kept oil and natural gas underground for millions of years,” she said.

Mr Magnus Killingland, global segment lead for hydrogen, ammonia and sustainable fuels at classification society DNV, said that Northern Lights CCS is an important first step to establishing value chains that can be replicated globally.

“The project serves as a demonstration of the feasibility and effectiveness of CCS, and clarifies several technical challenges, principles and possible best practices, demonstrating this for further investment and development in the technology,” said Mr Killingland.

According to a 2023 report by the International Energy Agency, to reach the global target of net-zero emissions by 2050, a global storage capacity of 1,000 million tonnes of CO2 is needed by 2030.

While planned capacities for CO2 transport and storage have surged in recent years, it is estimated to reach 615 million tonnes per year by 2030, which is still insufficient.

But developments have been gathering pace, with countries like Singapore announcing in 2024 its intentions to set up a cross-border CCS project with Indonesia.

Senior Minister of State for Sustainability and the Environment Amy Khor, who was at the Northern Lights visit in June, said that CCS is emerging in Asia as a promising solution to help countries transition to a low-carbon future.

“Companies such as Northern Lights offer Singapore useful insights on monitoring, reporting and verification processes, which will be key to upholding the environmental integrity of such projects. Similarly, it is also important to explore research and development efforts to help lower costs and improve outcomes for CCS projects. These will be useful learning points as we plan and develop a CCS project in our region.”

For CCS projects to be successful, the dollars and cents need to make sense. Commercial viability will allow CCS projects to scale up to levels needed to make a significant impact on global emissions.

DNV’s Mr Killingland pointed out that a CCS business case is profitable only if the emission cost is higher than the cost of permanently storing it. Given that Northern Lights is a pilot project, it is not expected to make high profits, and its partners look at this as a first step for developing a new industry.

Ms Staalesen said that expansion plans for phase 2 of Northern Lights will have to move in line with market developments and maturation of additional commercial agreements. She added that the project is talking to industries across Europe like bio-energy, chemicals and steel.

Voluntary carbon markets are expected to play a significant role in advancing CCS, said Ms Staalesen, raising the example of Danish power plant Orsted.

Voluntary carbon markets allow private players to buy and sell carbon credits that represent reductions or removals of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

Orsted has signed a commercial agreement to store 430,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions a year with Northern Lights, and also entered into an agreement with Microsoft for the tech company to purchase 3.67 million tonnes of carbon removal credits from the power plant.

Underpinning the voluntary carbon market are carbon offsetting methodologies that provide the scientific and technical backbone for ensuring that credits traded are real, measurable and verifiable.

Northern Lights is playing a key role in Europe’s CCS+ Initiative, which aims to develop robust carbon accounting methodologies for carbon capture, utilisation and storage.

“Confidence in the quality of the carbon credits generated depends on whether the methodology developed is robust and can stand up to international scrutiny,” said Mr Anshari Rahman, director of policy and analytics at Temasek-backed investment platform GenZero.

“Revenue from carbon finance can help improve the economics of CCS projects and finance the adoption of costly CCS technologies,” said Mr Anshari. He pointed out that costs for CCS projects vary greatly and can range from US$15 (S$20) to US$120 per tonne of carbon capture, depending on specifics such as emissions source and capture technology.

In the case of CCS, its technologies are complex and vary significantly across different geologies and industrial applications, said Mr Anshari.

“Developing a one-size-fits-all methodology that accurately captures these differences and balances scientific rigour with practicality is challenging,” he said.

“However, this may be a necessary investment to enable market participation for new actors and new solutions. Credible methodologies can unlock the full potential of CCS projects by attracting investment through informed economics.”

Singapore’s stable political climate and strong rule of law position the nation as a conducive venue to convene industry leaders, governments and environmental experts to drive the development of carbon markets and methodologies, said Mr Anshari.