US scientists create gel that attracts coral babies in drive to restore reefs

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

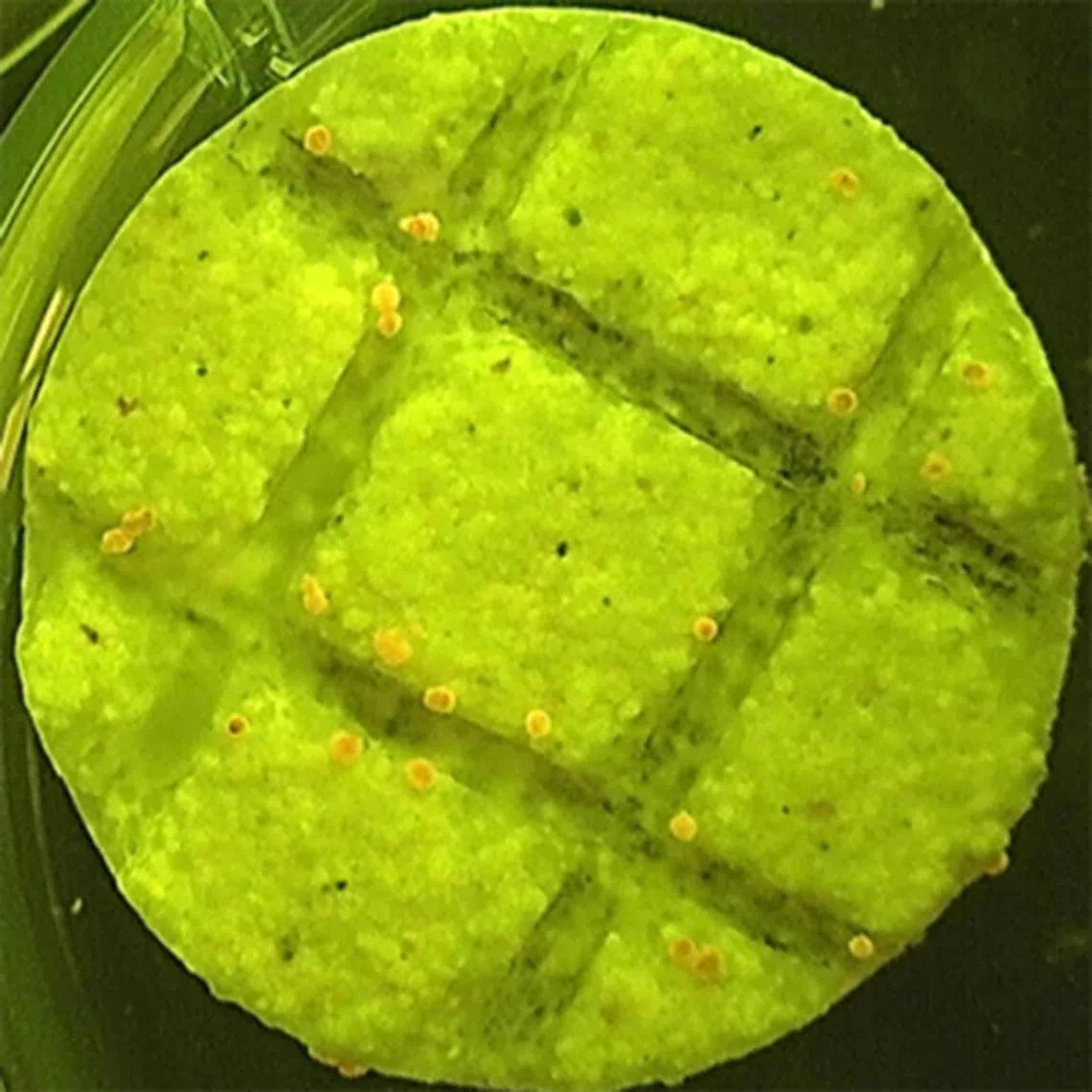

Experiments for this study were conducted on the Hawaiian stony coral species Montipora capitata.

PHOTO: CHRIS WALL

SINGAPORE – In efforts to give life to degraded reefs, researchers from San Diego have created a gel that draws coral larvae to settle on dying or artificial reefs.

The gel emits a scent that corals associate with healthy reefs. Coral larvae are picky about where they attach to, and if they fail to settle, they will be eaten by predators or washed out to sea.

When researchers from the University of California (UC) San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography coated a man-made surface in the lab with the gel, it drew about 20 times more coral babies than an untreated surface.

The tank experiment involved one Hawaiian coral species – the stony Montipora capitata.

While more studies are needed to prove that the gel can work with other corals, this innovation is among several that have emerged to save the world’s reefs, which are threatened by climate change and habitat destruction.

Singapore is home to a variety of corals, including more than 250 species of hard corals.

The reefs here serve as habitats for more than 100 species of reef fish and about 200 species of sea sponges, as well as rare and endangered seahorses and clams, among other marine life.

Other research includes running electricity through corals to speed up their growth – which has been trialled in Singapore – and “coral IVF”. In the latter initiative, scientists in Australia collect the eggs and sperm of resilient corals and rear the larvae in inflatable pools, before releasing them to reefs.

The world’s coral reefs are facing the most prolonged and widespread bleaching in recorded history, with more than 80 per cent affected by marine heatwaves. When corals get stressed by high ocean temperatures, they expel the algae that give them their striking colours and turn a ghostly white, which is known as bleaching.

From January 2023 to March 2025, bleaching-level heat stress impacted 84 per cent of the world’s reefs, the International Coral Reef Initiative said.

Singapore’s corals – which were not spared by mass bleaching in 2024 – have mostly recovered, with an estimated 5 per cent of corals left dead after the episode, The Straits Times reported in April.

A significant hurdle in coral reef restoration is getting coral larvae to settle on degraded reefs, or attach to artificial structures that might not smell like home to the larvae.

“I’m over-hearing that corals are dying – I’m more interested in what we can do about it,” said marine biologist Daniel Wangpraseurt in a statement on May 14. Dr Wangpraseurt, who is from Scripps Institution, led the study, which also includes the Jacobs School of Engineering at UC San Diego.

The scientists created the gel – called Snap-X – using nanoparticles that slowly release some of the coral larvae’s favourite scents underwater. These scents come from a type of crusty algae called crustose coralline. This type of red algae is found in Singapore’s waters.

Coral larvae settling on a surface coated with the gel.

PHOTO: CORAL REEF ECOPHYSIOLOGY AND ENGINEERING LAB

Past work here has shown that underwater surfaces – such as rubble or reefs – that have the local version of the algae present will attract more larvae, said Dr Jani Tanzil, facility director at St John’s Island National Marine Laboratory.

Research by scientists from the National University of Singapore has shown that the presence of the algae induces higher settlement not only for coral larvae, but also for other marine animals as well, like the threatened giant clams, she added.

The UC San Diego scientists used microscopic particles made of silica to hold the chemical compounds extracted from the algae. They suspended these nanoparticles in a liquid gel that would solidify and stick to a surface like Jell-O when exposed to ultraviolet light.

This resulting gel, Snap-X, releases the chemicals, which draw coral larvae for up to one month – long enough to capture an annual coral spawning event that lasts from a few days to a week. Coral spawning is the simultaneous release of eggs and sperm by corals.

In lab tests, Snap-X increased coral settlement by up to sixfold compared with an untreated surface. In additional experiments that featured water flow that better simulated reef environments, larval settlement expanded by up to 20 times.

The study’s findings were published in scientific journal Trends In Biotechnology on May 14.

“Biomedical scientists have spent a lot of time developing nanomaterials as drug carriers, and here we were able to apply some of that knowledge to marine restoration,” said Dr Wangpraseurt.

He suggested that the gel could be adapted to other coral species or marine regions by loading Snap-X with chemicals collected from suitable crustose coralline algae that are locally present.

Singapore recently embarked on a years-long mission to plant 100,000 corals in its waters

Dr Tanzil, commenting on the research and how applicable it can be for the Republic’s reefs, pointed out that the settlement of the larvae on the gel does not mean all of them will grow into adult corals.

The next step is recruitment, which refers to corals that survive for a significant period of time after settlement.

“In Singapore, we have high sedimentation (in the water) and competition from other organisms such as algae and tunicates. Although we can have high settlement rates, there is also high post-settlement mortality,” she noted.

“If mortality is high, then recruitment rates and recovery will be low. Any restoration methods deployed will need to consider the local environmental challenges,” added Dr Tanzil.

Singapore’s coral restoration project largely involves growing fragments trimmed from adult corals. These nubbins are reared in tanks at the Marine Park Outreach and Education Centre on St John’s Island before they are transplanted out at sea. As the transplanted corals are clones of the adult corals, genetic diversity may be limited.

Dr Tanzil’s colleague Lionel Ng, a research fellow involved in the restoration work, said the US project is promising in potentially helping to improve the genetic diversity of reefs. This is because, unlike the fragments, corals produced from sexual reproduction could have genetic make-ups with beneficial traits such as resilience to disease and environmental stressors.

But he added that field tests in the ocean are needed to understand how larvae from other coral species respond to the gel.

Dr Tanzil added: “I think the new method to induce larval settlement is exciting. It allows for a new means to incorporate such chemical compounds onto new substrates such as coastal protection structures.”

Shabana Begum is a correspondent, with a focus on environment and science, at The Straits Times.