ST Explains: What happens to oil-soaked sand after it is removed from S’pore’s coastline

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Mencast sales and business development manager Irni Masnita Mohamed Anis (centre), showing a bag of treated sand at the treatment facility on June 21.

ST PHOTO: KEVIN LIM

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Oil-soaked sand removed from Singapore’s beaches following the June 14 oil spill

Ms Irni Masnita Mohamed Anis, sales and business development manager at Mencast Offshore and Marine, said tests will be done on the treated sand to assess its safety, but the final decision on what the sand will be used for depends on its owner.

The sand treated by Mencast is from East Coast Park and Sentosa’s Siloso, Tanjong and Palawan beaches.

It is not clear what will happen to treated sand that does not pass inspections.

Ms Irni was speaking to The Straits Times on June 21, during a media visit facilitated by the National Environment Agency (NEA) to a treatment facility.

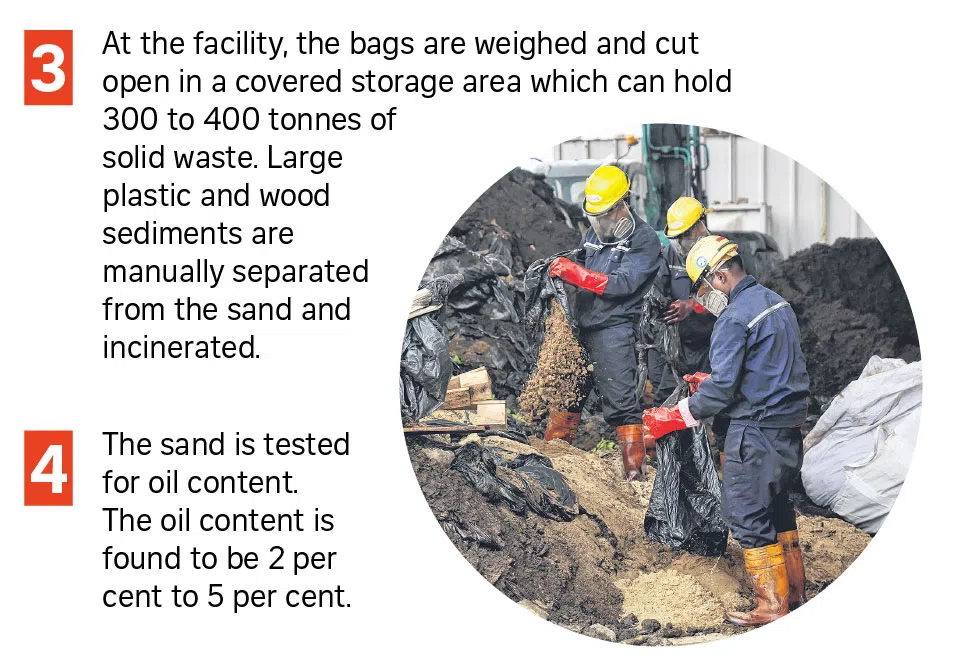

She said that the oil content in sand contaminated from the recent spill ranges from 2 to 5 per cent.

For the sand to be considered successfully treated, the oil content has to drop to about 0.1 per cent.

Treated sand, despite being safe to touch, may still appear to be stained black.

Ms Irni said it cannot be restored to its original white colouration.

So far, about 140 tonnes of oil-soaked sand have been collected by Mencast, she said.

Minister for Sustainability and the Environment Grace Fu said in a Facebook post on June 20 that o ver 71,000kg of sand were scooped up

On June 14, the Netherlands-flagged dredging boat Vox Maxima hit the stationary Singapore-flagged bunker vessel Marine Honour

Treating oil-soaked sand

Intensive cleanup efforts have been under way, though eliminating all traces of the low-sulphur oil spilled may prove to be a long-term undertaking.

Despite a week of cleanup efforts, the foreshore in East Coast Park remains marred by streaks of oil on June 20.

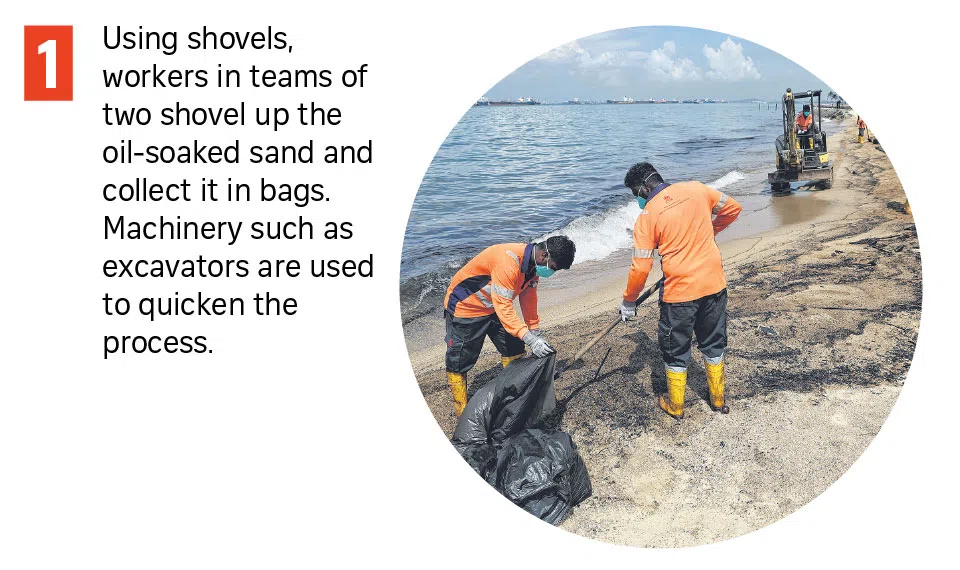

To clean up a contaminated beach, workers don personal protective equipment, including safety boots, N95 masks and gloves, and work in pairs to shovel oil-soaked sand into black trash bags.

It is back-breaking work, with each person handling dozens of bags weighing approximately 4kg each, all under the hot sun.

To quicken the process, larger piles of sand are dug up using excavators, to be bagged later.

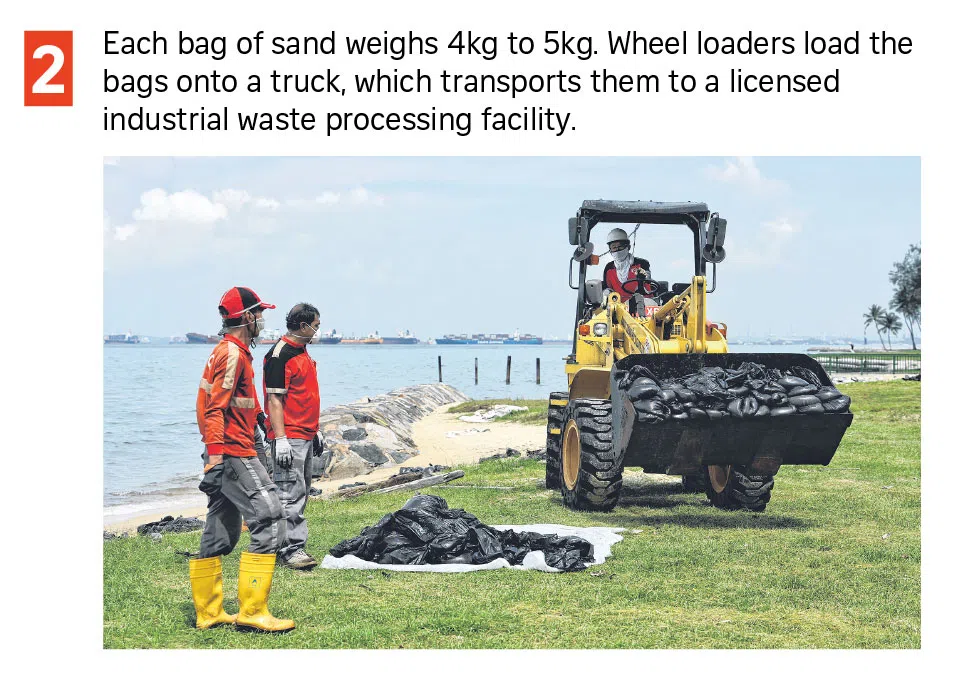

Once sufficient bags of oil-soaked sand have been collected, they are put into a wheel loader – a four-wheel machine designed for lifting – and then transferred into a skid tank.

The tank, which is attached to a hook lift truck, allows for waste to be transported to toxic industrial waste facilities such as Mencast.

Ms Irni said treatment efforts at the Mencast plant began on June 20.

The skid tanks were deployed to beaches on June 17, and have since been depositing the collected sand at the plant.

Oil-soaked sand, first bagged by NEA-appointed contractors at the various beaches, must be “unbagged” manually at the Mencast facility before the start of the treatment process.

Workers wearing gloves, goggles and work boots must physically cut through such bags to feed the contaminated sand through the facility’s treatment systems.

Large plastic and wood sediments are also removed during this process to be incinerated.

As at June 21, about 30 per cent of Mencast’s workforce comprising about 60 people have been allocated specifically to waste processing efforts following the oil spill.

Sand samples are also taken to the laboratory for contaminant testing to determine the required treatment temperature and duration.

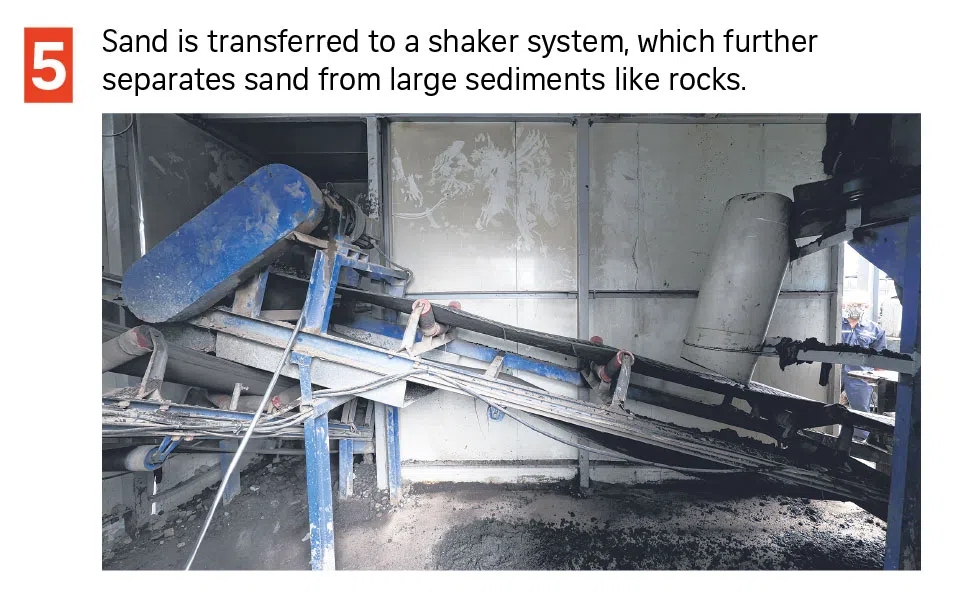

The contaminated sand is then transferred to a shaker system, which filters out coarser debris such as rocks and plastic shards from the sand to be compressed.

This is so that the particles are the same size as the sand grains, to ensure that all the oil can be effectively vaporised during treatment.

The oil-soaked sand is then sent to be heat-treated.

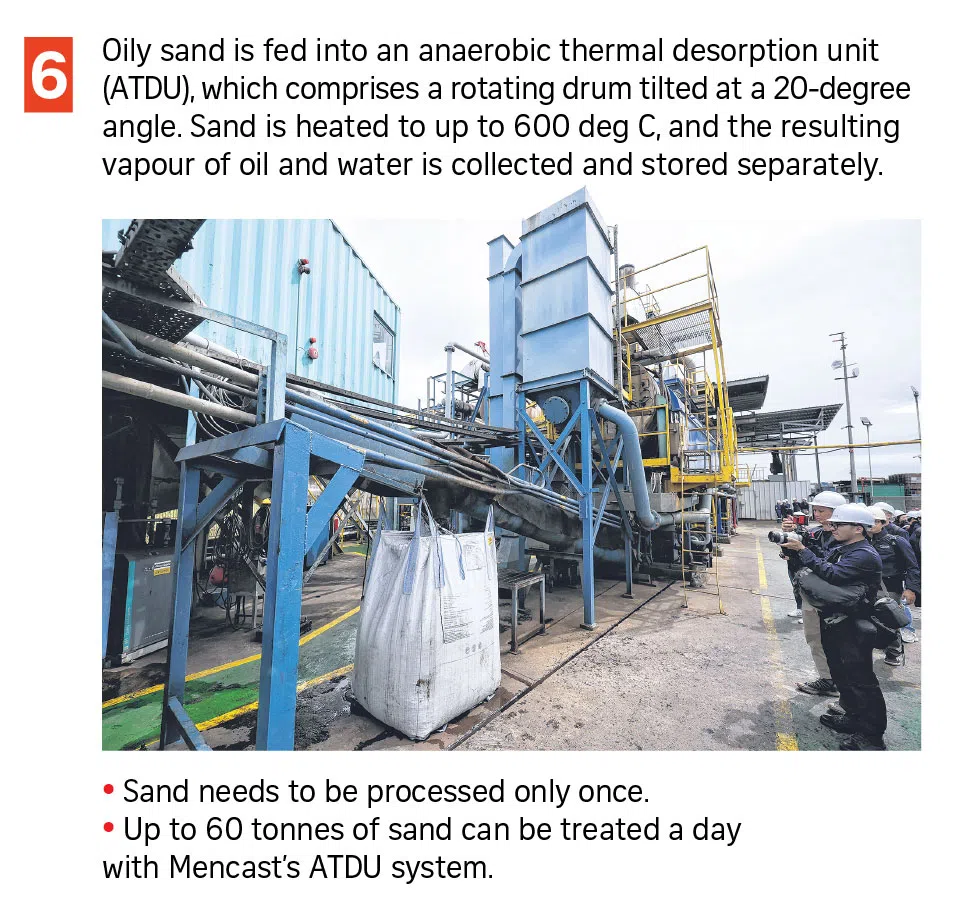

To date, about 12 tonnes of contaminated sand have been processed through the facility’s anaerobic thermal desorption unit (ATDU).

Here, oil-soaked sand is heated in a rotating drum at approximately 600 deg C, turning contaminants such as oil into vapour after about 45 minutes.

The ATDU system can treat up to 60 tonnes of sand a day.

Treated sand is then stored and tested for further contaminants.

Mencast reports that for sand which has about 2 to 5 per cent oil content, the treatment will bring the oil content down to about 0.1 per cent.

It said the treated sand will be assessed for future potential use, such as for filling sandbags for flood control.

It is, however, dependent on “analysis and tests which have not been finalised yet”, in addition to discussions with owners of the sand as to what should be done with the treated sand, it added.

Oil retrieved from the shore may also be recycled and blended with Mencast’s existing resources as “recovery oil”, which is sold to oil traders.

Still, the treatment of oil-soaked sand is essential, regardless of its final outcome.

If disposed of without proper treatment, oil-soaked sand remains harmful to the environment.

“That’s why we are here.

“Anything that is contaminated (with oil) is toxic, and has to be treated in a proper manner,” Ms Irni said.