Science Journals: Waves of change for Singapore’s coral reef research

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Since the 1980s, there has been a sea change in Singapore’s efforts to bring its reefs back to life.

PHOTO: JONATHAN TAN

Coral biologist Huang Danwei has one piece of advice for explorers of the reef: Never ignore your cuts.

In 2009, he scraped against coral while diving in the Philippines as part of his PhD research on coral diversity. He ignored the wound and hoped it would heal on its own.

But it festered and he ended up spending a week in hospital when he got back to Singapore. He eventually recovered after taking a cocktail of antibiotics.

Such cuts can be a problem because the natural bacterial mix in coral also includes pathogens that are known to cause disease in humans. Dr Huang’s encounter with the hidden world of coral microbes would not be his last.

Now an associate professor at the National University of Singapore (NUS), Dr Huang counts among his research interests a desire to learn more about the tiny things that most people do not see or immediately think about when they look at a coral reef.

“Every organism is an ecosystem,” said Dr Huang, deputy head of the NUS Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. “The microscopic life – the microbes that live in the coral – all contribute to the functioning of the ecosystem.”

Among the most well known of coral microbes are zooxanthellae, single-celled algae that provide the coral with nutrition. But the coral microbiome comprises more than these photosynthetic organisms. For the coral, microbes are part of its defence against external threats, such as rising sea surface temperatures.

In the human world, some relationships fall apart at the first sign of trouble. Yet in other matches, one helps the other through tough times. So too in the coral world do these fortuitous couplings exist, with specific pairings between coral and microbiome conferring the organism with more resilience against heat stress.

“Depending on the association between the coral and its microbes, the coral can be more resilient to stress,” said Dr Huang, who also leads the NUS Reef Ecology Laboratory.

What these pairings are is something that Dr Huang wants to find out.

With a research grant he received under the Marine Climate Change Science Programme, Dr Huang and his team will play matchmaker, looking for the best matches between coral and microbes which allow the holobiont (referring to both the coral itself and its microbiome) to survive in an ocean set to boil.

The programme was launched in 2021 by the National Parks Board (NParks).

Dr Huang’s research joins a host of other research projects taking off in Singapore that aim to look at how coral reefs can withstand the impacts of climate change.

Even the name of the programme his research is funded under provides a clue – the Marine Climate Change Science programme, earlier known as the Marine Science Research and Development Programme.

This focus on climate resilience marks a new chapter in the story of Singapore’s coral reef science journey, which previously had a large focus on how reefs can bounce back after loss or degradation due to coastal development.

“This change is something that is reflected globally as well,” said Dr Jani Tanzil, the facility director at Singapore’s St John’s Island National Marine Laboratory.

“Coral reefs are still facing many local threats, like coastal development, urbanisation and sedimentation. But now they also have to deal with climate change.”

Climate change, caused by an ever-thickening blanket of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, is a global problem.

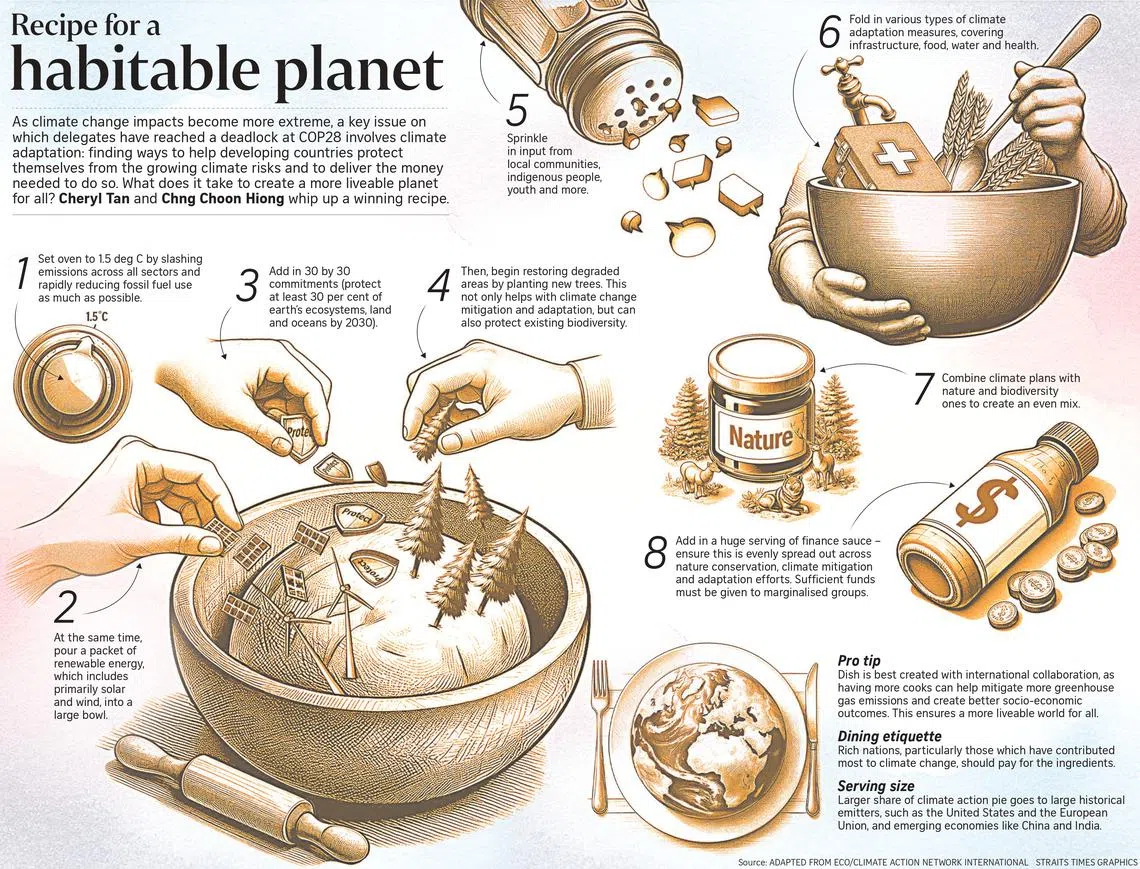

Countries are gathering in Dubai from Nov 30 to Dec 12 for COP28, the United Nations climate change conference, to galvanise climate action and call on nations to taper down the use of fossil fuels to limit global warming.

But it may take some time yet for global politics – and national policies – to catch up with what the science clearly points to.

In the interim, research efforts that look into increasing the resilience of Singapore’s remaining coral reefs, which are clinging on despite the odds, will be paramount if they are to have a fighting chance of survival in a warming planet.

A story of loss and hope

The history of Singapore’s coral reefs could, depending on how you look at it, be a tragedy or offer a glimmer of hope. Over 60 per cent of coral reefs in the city-state have been lost over the years due to reclamation and coastal development works. Yet life still persists.

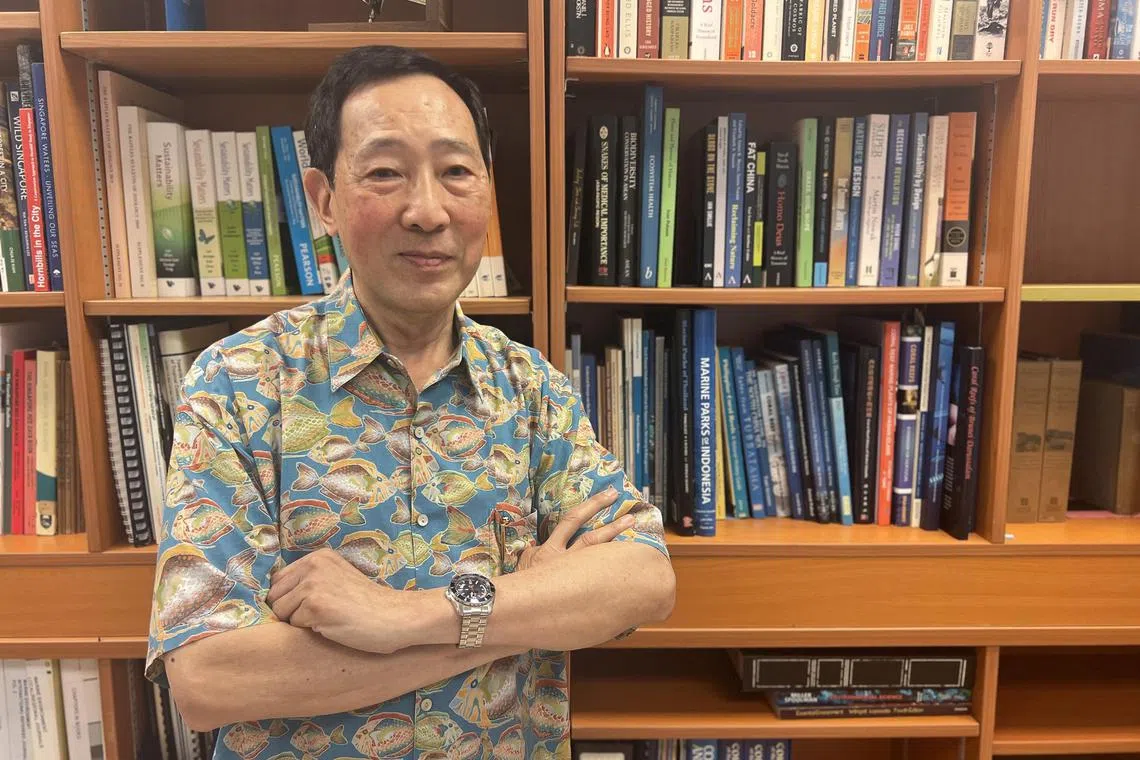

Emeritus Professor Chou Loke Ming Prof Chou started the Reef Ecology Laboratory at NUS, and studied various types of reef life

PHOTO: AUDREY TAN

NUS Emeritus Professor Chou Loke Ming, a pioneer in Singapore’s marine science and conservation community, saw first-hand the impact of the country’s early coastal works.

“In the 1960s, the water was clear. Standing on the boat, you could look down and see corals all the way down the reef slope, to depths of 10m or more. I was so taken by their beauty,” he recalled. Today, coral life is now found mainly in shallower waters, at depths not exceeding 5m.

In 1977, Prof Chou started the Reef Ecology Laboratory at NUS, and studied various types of reef life – from tropical fish to nudibranchs (sea slugs).

The lab in 1989 started testing the feasibility of deploying man-made structures – including hollow concrete cubes and tyre-pyramid modules – to improve fish stocks.

It also conducted a number of reef surveys, with Prof Chou and his colleagues recording species diversity and abundance at various sites. But there was no standardised survey method then, making it hard to compare results across sites in Singapore or even the region, he said.

In the late 1980s, Prof Chou was among marine biologists from South-east Asia who took part in the Asean-Australia Coastal Living Resources Project. That effort resulted in the development of standardised sampling protocols.

For Singapore, it also resulted in a useful database of information on the Republic’s coastal resources, including mangroves, coral reefs, and soft-bottom benthic (or bottom-dwelling) communities, which include worms and molluscs.

These developments laid the groundwork for the next phase of marine research efforts in the country: bringing a dying seafloor back to life.

Healing a reef

In Singapore, mitigation measures usually involve relocation of coral colonies away from sites due to be reclaimed to locations where they can, hopefully, take root and grow.

One of the earliest recorded efforts to do so was in the early 1990s, when the Nature Society (Singapore) called on over 400 volunteers to shift coral colonies from sites in the southern part of the country due to be reclaimed to Sentosa.

Barely 10 per cent of the translocated coral survived due to various factors, including an inappropriate choice of recipient site – the area was often subjected to surge and heavy sedimentation – and improper methods in securing fragments to substrate that caused the baby corals to be washed away.

That episode, however, had a silver lining – it led to improvements in coral relocation techniques and subsequent mitigation projects.

In the early 2000s, there was a global shift towards taking a “gardening approach” to reef restoration, said Dr Tanzil.

Inspired by the forest restoration efforts on land, the global coral community reasoned that a two-step protocol – “gardening” small colonies in nurseries and then transplanting them to damaged areas – could improve the chances of rejuvenating a reef.

In Singapore, too, the movement took off, with coral research coalescing around two parallel tracks: the development of artificial reefs for reef restoration, and the use of coral nurseries.

Dr Tanzil, also a senior research fellow at the NUS Tropical Marine Science Institute, started her career as a research assistant in Prof Chou’s Reef Ecology Laboratory in 2004. By that time, she had been volunteering with the lab for two years and had been trained in various reef survey methodologies.

One of her first projects was to monitor coral recruitment on the reef enhancement units (REU) deployed in Singapore’s southern islands under a collaboration between NUS and the Singapore Tourism Board (STB).

That effort, which began in 2001 – about a decade after Prof Chou’s lab first deployed concrete modules and tyre pyramids in Singapore – had a different focus. Instead of acting as fish aggregation devices, the REUs were being assessed on their ability to rejuvenate the coral reef to promote coastal tourism.

Prof Chou said that that project had focused on the natural recruitment of corals, although fragments were attached to the REUs if researchers came across them on the seafloor. Dr Tanzil mused: “At that point, we had no nursery, we just took corals of opportunity – what we called broken coral fragments on the seafloor – and attached it to the artificial reef frame using epoxy.”

But this was set to change.

By the mid-2000s, the coral gardening concept in Singapore was picking up steam.

The first coral nurseries were established in the southern waters to test if in-situ nurseries would be successful given the turbid conditions. Around that period, NUS was also involved in a project funded by the European Union to restore Indo-Pacific coral reefs in Singapore, the Philippines and Thailand, using the gardening approach.

Context in coral restoration is of the utmost importance, said Dr Karenne Tun, another protege of the Reef Ecology Lab under Prof Chou. Now the director of the terrestrial, coastal and marine branches at NParks’ National Biodiversity Centre, Dr Tun said coral restoration techniques must be tailored to local contexts.

For example, in countries where the waters are clearer, coral fragments can be transplanted directly onto degraded reefs and thrive.

In Singapore, the chances of this being successful were lower due to the rubbly nature of the seafloor that made it difficult for the baby corals to gain a foothold.

The size that coral fragments should grow to before transplantation is also different in Singapore, she said. “In other countries, nubbins (fragments) about 1cm or 2cm long can be transplanted and survive. But we found that in Singapore, fragments that grow to at least 10cm long stand a better chance of survival,” Dr Tun added.

Eventually, the research paid off, with higher coral survival rates in subsequent translocation exercises.

In 2013, the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore funded a project to move corals from the Sultan Shoal, south-west of Singapore, to protect them from the impact of the Tuas Terminal development. Over 80 per cent of corals survived the move – a marked improvement from the low survival rates from the effort in the early 1990s.

Waves of change

As the knowledge base of coral restoration science in Singapore accumulated, concerted efforts to protect the nation’s marine biodiversity began to take shape.

Coral reef scientists in Singapore are continuing to push the frontiers of coral reef science, from growing corals on plastic toy blocks to maximise yield, to translocating nubbins to deeper, light-limited waters, where almost all corals have vanished.

At the same time, what was once an endeavour among academics gradually expanded to become more inclusive, involving government agencies, the private sector and civil society.

Ground-up “blue plans”, developed by marine conservationists, scientists and volunteers, were published in 2001 and 2009, calling on the Government to protect Singapore’s marine treasures.

In 2014, the country designated its first marine park – the Sisters’ Islands Marine Park.

PHOTO: NPARKS

In 2014, the country designated its first marine park – the Sisters’ Islands Marine Park – which agent-based modelling had shown was Singapore’s “mother reef” that seeds coral larvae to other marine habitats.

A community group, Friends of the Marine Park, was also established to promote stewardship and responsible use of the area.

The most recent edition of the blue plan – which outlines six recommendations, including improved laws to protect marine environments and formalised management systems for these areas – was published in 2018.

NParks also rolled out biodiversity impact assessment guidelines for marine spaces in 2020, helping to set minimum standards for such studies, which had previously differed among consultants. Previously, there was no locally standardised methodology for how such surveys should be conducted.

Most recently, in June 2023, NParks announced its most ambitious coral restoration plan to date: grow baby corals in nurseries and plant 100,000 of them at degraded coral reef sites

Since the 1980s, there has been a sea change in Singapore’s efforts to bring its reefs back to life.

For Prof Chou, whose career charts the progress of coral reef science in Singapore – from baseline mapping to artificial reef deployment and nursery development – the current research frontier looks at how these important habitats can be made more resilient in the face of climate change.

This includes the work that Dr Huang – who took over the reins of the Reef Ecology Lab when Prof Chou, his mentor, retired in 2014 – is doing on the coral microbiome, as well as other projects looking into green-grey coastal infrastructure to protect the country from sea-level rise.

ST ILLUSTRATION: CHNG CHOON HIONG

In November 2022, Prof Chou was named an Asean Biodiversity Hero for his pioneering work on coral reef restoration and management. The award recognises passionate individuals in Asean who have dedicated their lives to protecting biodiversity.

Asked for his advice for the next generation of marine biologists, he said: “Don’t give up. You may feel like you are alone, fighting the system. But you are not alone, there are many people out there with you. Not all of them are scientists, but they are also with you in advocating for marine conservation.”

Having watched the decline and resurrection of the country’s reefs, Prof Chou remains optimistic about their future.

“When I first started in coral reef research, many people were talking about how coral reefs are fragile, break easily, and (are) unable to handle large disturbances. But that’s not the case for our reefs, and going forward, with new technology and new science, anything is possible.”

Audrey Tan is the science communications lead at the National University of Singapore’s Tropical Marine Science Institute. She is a recipient of the science communication fellowship of the International Coral Reef Society (ICRS). A version of this article first appeared in the December issue of Reef Encounter, an ICRS magazine-style publication.