Science Briefs: New findings about oldest human remains

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

New findings about oldest human remains

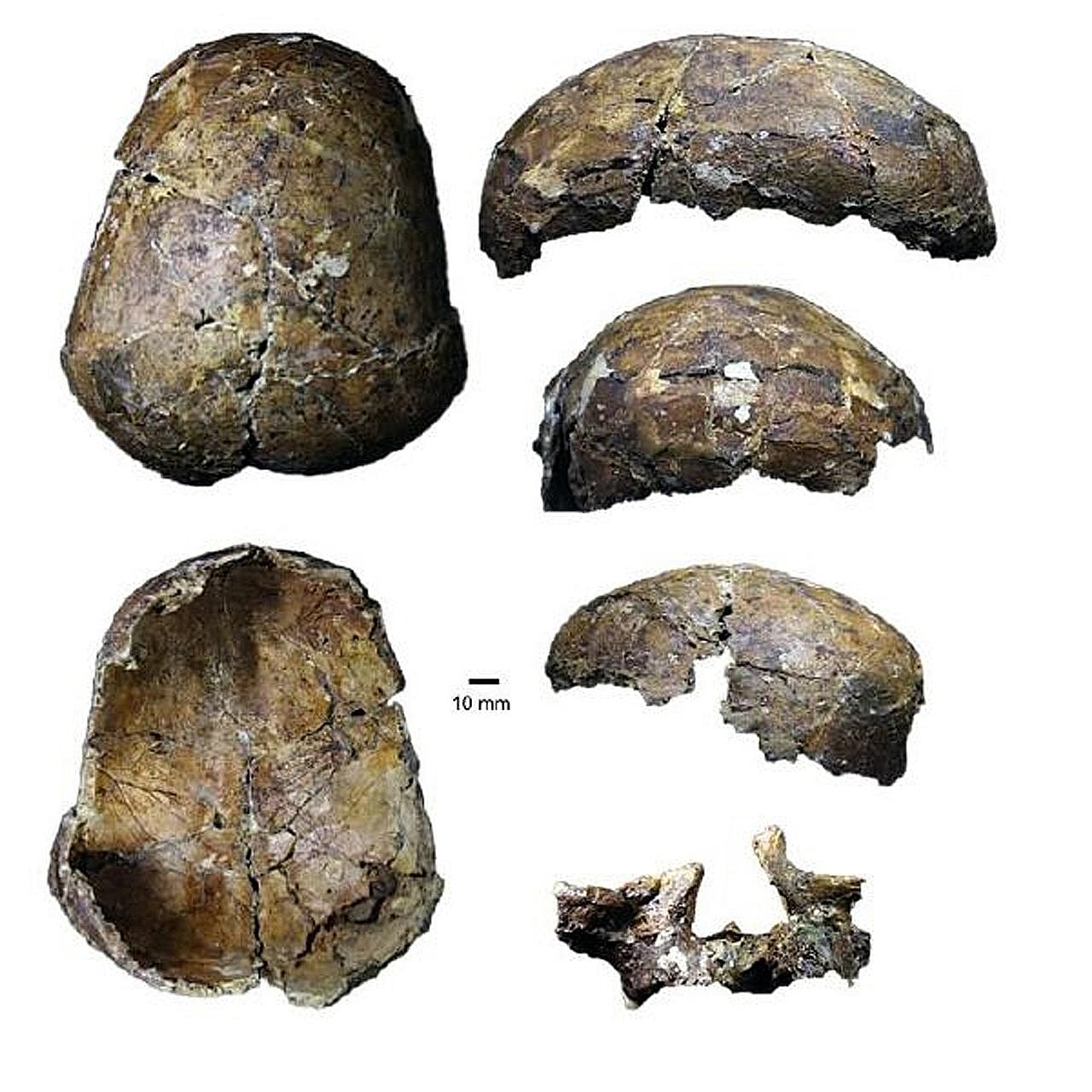

The 37,000-year-old Deep Skull - the oldest modern human remains found in South-east Asia - may not be related to indigenous Australians, as had been thought originally.

The skull is also likely to have been the remains of a woman, rather than a teenage boy.

These conclusions were reached by a team of researchers - led by University of New South Wales associate professor Darren Curnoe - in the most detailed investigation of the ancient cranium since it was found at the Niah Cave complex in Sarawak in 1958.

The study, by Prof Curnoe and researchers from the Sarawak Museum Department and Griffith University, is published in the journal Frontiers In Ecology And Evolution.

Researchers concluded in 1960 that the Deep Skull belonged to an adolescent male and represented a population of early modern humans closely related, or even ancestral, to indigenous Australians.

A recent study of the 37,000-year-old Deep Skull is challenging old ideas, including the belief that it belonged to a teenage boy.

PHOTO: CURNOE

The team studied the morphology of the skull, the degree of fusions of bone on the skull, and other attributes including tooth wear that can be used to estimate a person's age.

"Our study challenges many of these old ideas. It shows the Deep Skull is from a middle-aged female rather than a teenage boy, and has few similarities to indigenous Australians.

"Instead, it more closely resembles people today from more northerly parts of South-east Asia," said Prof Curnoe.

The new study challenges the hypothesis that South-east Asia was settled initially by people related to indigenous Australians and New Guineans, who were then replaced by farmers from southern China a few thousand years ago.

The study suggests that - in Borneo at least - the earliest people on the island were much more like indigenous people living there today rather than indigenous Australians.

It also suggests that at least some of the indigenous people of Borneo were not replaced by migrating farmers, but instead adopted the new farming culture when it arrived around 3,000 years ago.

Micro-camera can be injected with a syringe

German engineers have created a camera no bigger than a grain of salt that could change the future of health imaging - and clandestine surveillance.

Using 3D printing, researchers from the University of Stuttgart built a three-lens camera, and put it on the end of an optical fibre the width of two hairs.

Such technology could be used for minimally invasive endoscopy to explore the human body, the engineers reported in the journal Nature Photonics.

It could also be deployed in virtually invisible security monitors.

3D printing - also known as additive manufacturing - makes three-dimensional objects by depositing layer after layer of materials such as plastic, metal or ceramic.

Due to manufacturing limitations, lenses cannot currently be made small enough for key uses in the medical field, said the team, which believes its 3D printing method may represent "a paradigm shift".

It took only a few hours to design, make and test the tiny eye, which yielded "high optical performances and tremendous compactness", the researchers reported.

The compound lens is 0.1mm wide, and 0.12mm with its casing.

It can focus on images from a distance of 3mm, and relay them over the length of a 1.7m optical fibre to which it is attached.

The imaging system fits comfortably inside a standard syringe needle, allowing for delivery into a human organ, including the brain.

"Endoscopic applications will allow for non-invasive and non-destructive examination of small objects in the medical as well as the industrial sector," the engineers wrote.

The compound lens can also be printed onto image sensors such as those used in digital cameras.

AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE

Gut bacteria linked to chronic fatigue syndrome

Physicians have been mystified by chronic fatigue syndrome, a condition in which normal exertion leads to debilitating fatigue that is not alleviated by rest. There are no known triggers, and diagnosis requires lengthy tests administered by an expert.

Now, for the first time, Cornell University researchers report that they have identified biological markers of the disease in gut bacteria and inflammatory microbial agents in the blood.

A study done on 48 people with the condition, using microbial DNA from their stool samples, was published in the journal, Microbiome.

"Our work demonstrates that the gut bacterial microbiome in chronic fatigue syndrome patients isn't normal, perhaps leading to gastrointestinal and inflammatory symptoms in victims of the disease," said Professor Maureen Hanson from the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics at Cornell, and the paper's senior author.

"Furthermore, our detection of a biological abnormality provides further evidence against the ridiculous concept that the disease is psychological in origin."

Apart from using the finding as a complement to other non-invasive diagnoses, it could also allow clinicians to consider changing diets, using prebiotics such as dietary fibre or probiotics, to help treat the disease," said Mr Ludovic Giloteaux, a postdoctoral researcher and first author of the study.

However Mr Giloteaux added that there is still no way to say whether the altered gut microbiome is a cause or a consequence of disease.

Next, the research team will look for evidence of viruses and fungi in the gut, to see if one of these or an association of these along with bacteria may be causing or contributing to the illness.

Compiled by Samantha Boh