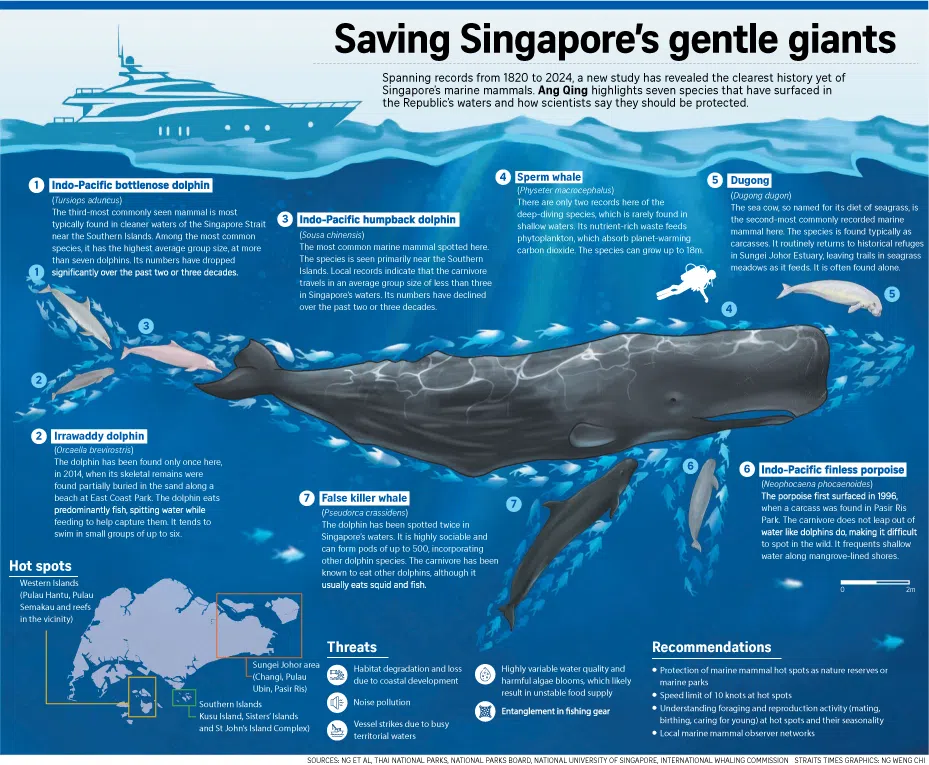

NUS study calls for reduced boat speeds, limited entry near S’pore marine mammal hot spots

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Gentle giants like the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin have endured in Singapore’s territorial waters.

PHOTO: NPARKS

- NUS scientists urge increased protection for marine mammals in Singapore's waters, identifying hotspots near the Sungei Johor Estuary, the Southern Islands and the Western Islands.

- Research suggests reduced vessel speeds and restricted entry in hotspots can mitigate boat strikes, mirroring protection in Queensland.

- The study spanned records from 1820 to 2024, a journey that occasionally involved identifying decomposed carcasses.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – Scientists from the National University of Singapore (NUS) are calling for the increased protection status of marine mammals, as well as reduced vessel speed limits and restricted entry in certain coastal areas to raise the chances of their survival.

Gentle giants like the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin and the dugong have endured in the Republic’s territorial waters

Marine mammals are a strong indicator of the health of ocean habitats, as they are sustained by large amounts of food and tend to have long lifespans.

The NUS study, published in interdisciplinary journal Ocean and Coastal Management in December, is thought to be the first comprehensive baseline for marine mammals in Singapore.

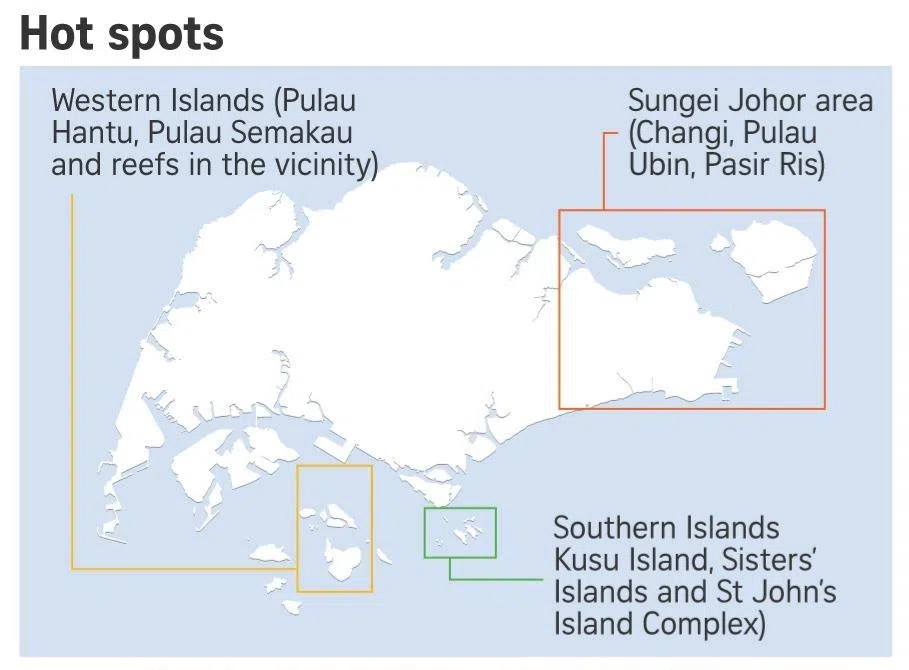

It compiled verified sightings spanning from 1820 to 2024 to identify the animals’ dynamics and hot spots, and found that the areas near the Sungei Johor Estuary, the Southern Islands and the Western Islands were hot spots for Singapore’s marine mammals.

To protect these habitats, the scientists recommended lowering vessel speed limits to 10 knots – which would effectively reduce the lethality of boat strikes to whales and dugongs – or restricting entry altogether.

The need for protection is urgent, as marine mammals in Singapore’s waters appear to be constrained to discrete but patchy areas amid declining resources.

The researchers found that pod sizes of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin and the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin have declined – most evidently over the past two or three decades.

“Before this review, there wasn’t a consolidated database for marine mammal occurrences,” said the study’s lead author Sirius Ng, an NUS doctoral candidate studying dugongs. “Most records that we have uncovered tend to be incidental observations by citizen scientists or research groups conducting fieldwork for other studies.”

It took a year to comb through a myriad of sources, which included a 19th-century museum record of a dugong collected by Sir Stamford Raffles, newspaper microfilms archived in the National Library and posts in Facebook groups.

The process occasionally involved forensic-level scrutiny, as the team had to painstakingly identify species from decomposed remains.

“Sometimes it’s a tail or half a body,” said Mr Ng. “There was a record one or two years ago within the Southern Islands... it was just the lower half of the body, but we could identify it as a dugong because of its distinct shape.”

Out of close to 300 reports, the team validated 124 records, confirming the presence of seven marine mammal species in Singapore.

The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin was the most common species, accounting for more than half of the verified records.

Both the species and the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin were frequently spotted off the Southern Islands. There were two accounts of both species swimming in the same pod together.

Surprisingly, dolphins were found to frequent urbanised areas rather than natural spaces.

Mr Ng said: “It could be that although our environment is becoming more urbanised, these organisms just keep returning to the same localities that have changed over time.”

An Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin spotted in the waters of Singapore.

PHOTO: CON FOLEY

Another hypothesis is that the dolphins have become habituated to Singapore’s urbanised coastline, he added, citing how dolphins in other countries have adapted to harnessing the urban environment, such as by feeding off fishing trawlers.

The second-most common marine mammal species detected was the elusive dugong, which is difficult to spot due to its shy nature and the murky coastal waters of Singapore.

“We have records of them, but much of their movements remains a mystery,” said Mr Ng. “They are hardly seen alive in the wild, except for low-clarity photographs taken... in the 2000s.”

A dugong grazing on seagrass.

PHOTO: ADOBE STOCK

A combination of live records, evidence of feeding trails and carcasses suggest that dugongs have inhabited the Sungei Johor Estuary since the 1820s.

This is despite these coastal spaces off Pulau Ubin, Pasir Ris and Changi being high-risk areas directly adjacent to international shipping lanes.

The researchers theorised that dugong mothers pass down knowledge of these movement corridors and seagrass patches to their calves, and that these busy zones could also harbour some areas of refuge.

Given the small populations of the marine mammals, the scientists recommended that conservation protection cover their hot spots in the Sungei Johor Estuary, the Southern Islands and the Western Islands.

Calls for protection of these areas were similarly made in the Singapore Blue Plan 2018, which had been submitted to the Government for consideration, they noted.

The proposal for conservation of marine ecosystems here was prepared by marine biologists, academics, volunteers and other stakeholders interested in the marine environment.

In the coming years, Singapore plans to reclaim some 1,000ha of land

“The biggest gap of protection for marine mammals currently stems from a lack of knowledge on their ecology in the local context,” said Mr Ng. “We hope that the findings will help Singapore balance urbanisation and the preservation of natural habitats.”

Dr Karenne Tun, the National Parks Board’s (NParks) group director for the National Biodiversity Centre, said the paper would be studied carefully to enhance the statutory board’s marine conservation and management strategy launched in 2015.

“The Marine Conservation Action Plan... emphasises the protection of critical habitats, sustainable management of marine resources, and the integration of conservation considerations into coastal development planning,” she said. She cited the designation of Singapore’s first marine park at Sisters’ Islands and the announcement of the Lazarus South-Kusu Reefs Marine Park

High levels of dolphin vocalisations detected off Sisters’ Islands and Kusu Island in the southern waters of Singapore played a key factor in safeguarding the location for the second marine park, she said. NParks supports further investigation into key stages of marine mammal life, as proposed by the scientists, and will continue to study acoustic data of Singapore’s marine megafauna collected by another NUS project, she added.

Members of the public can aid the effort to study Singapore’s marine mammals by submitting their findings to NUS database Mega Marine Life in Singapore at this website