Nanoplastics can accumulate in marine organisms' bodies, NUS research finds

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

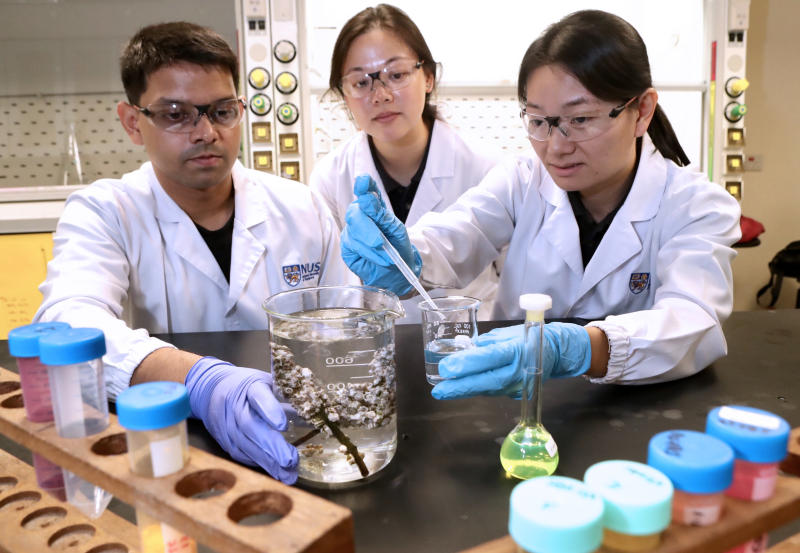

The research team used the acorn barnacle as a model organism in order to track the movement of the particles.

PHOTO: LIANHE ZAOBAO

SINGAPORE - Researchers here have found that some marine organisms may be able to retain tiny pieces of plastic in their bodies for several days.

This means that if these plastic pieces carry hazardous chemicals and are eaten by these organisms, aquatic food chains could be contaminated if these organisms are, in turn, eaten by others, say researchers.

National University of Singapore (NUS) scientists have found that one particular marine organism, the acorn barnacle, retained tiny plastics from larvae to adulthood, a span of about seven days.

Dr Serena Teo, senior research fellow from the Tropical Marine Science Institute at NUS who co-supervised the research, said at a media briefing on Thursday (May 31): "Hazardous chemicals can also be absorbed by the particles. So when the particles are eaten, they can be transferred from the particle to the organism."

The 1½-year research, which started in November 2016, aimed to track the accumulation and retention of nanoplastics in marine organisms throughout their lifespans.

Nanoplastic particles, which are less than one micrometre in size, are about a thousand times smaller than the plastic beads in facial scrubs and toothpastes.

The team used the acorn barnacle as a model organism in order to track the movement of the particles.

Mr Samarth Bhargava, one of the researchers, said: "We wanted to use barnacles as the model organism because the larvae are transparent, so while taking an image of them, we can actually see the plastics through imaging techniques."

The research team incubated the barnacle larvae in solutions with non-toxic nanoplastics, along with their regular feed under two different conditions.

The nanoplastics were created by the team themselves before being tagged with a fluorescent dye for visibility.

In the first condition, termed "acute", larvae were exposed to high concentrations of nanoplastics for about three hours.

Under the second, "chronic" condition, which is closer to a common marine environment, larvae were exposed to a low concentration of nanoplastics for up to four days.

In both cases, plastic particles were found to have accumulated and been distributed throughout the entire body of the larvae after being ingested.

Substantial traces of plastic were also retained in their bodies until they reached adulthood. Barnacles that had been exposed to plastics under the "chronic" condition generally retained a higher amount of nanoplastics.

The study was funded under the Marine Science Research and Development Programme run by the National Research Foundation Singapore.

The findings were published online in March in science journal ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering.

The team hopes to use the study as a launch pad for further understanding of the pathways of such plastic particles within the marine ecosystem, including the potential of these nanoplastics to move up the food chain.

NUS Department of Chemistry Associate Professor Suresh Valiyaveettil, who co-supervised the research, said: "The lifespan and fate of plastic waste materials in a marine environment are a big concern at the moment, owing to the large amounts of plastic waste.

"The team would like to explore such topics in the near future and possibly come up with pathways to address such problems."