No monsoon surge expected in Singapore this week despite heavy rain warnings in Malaysia

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

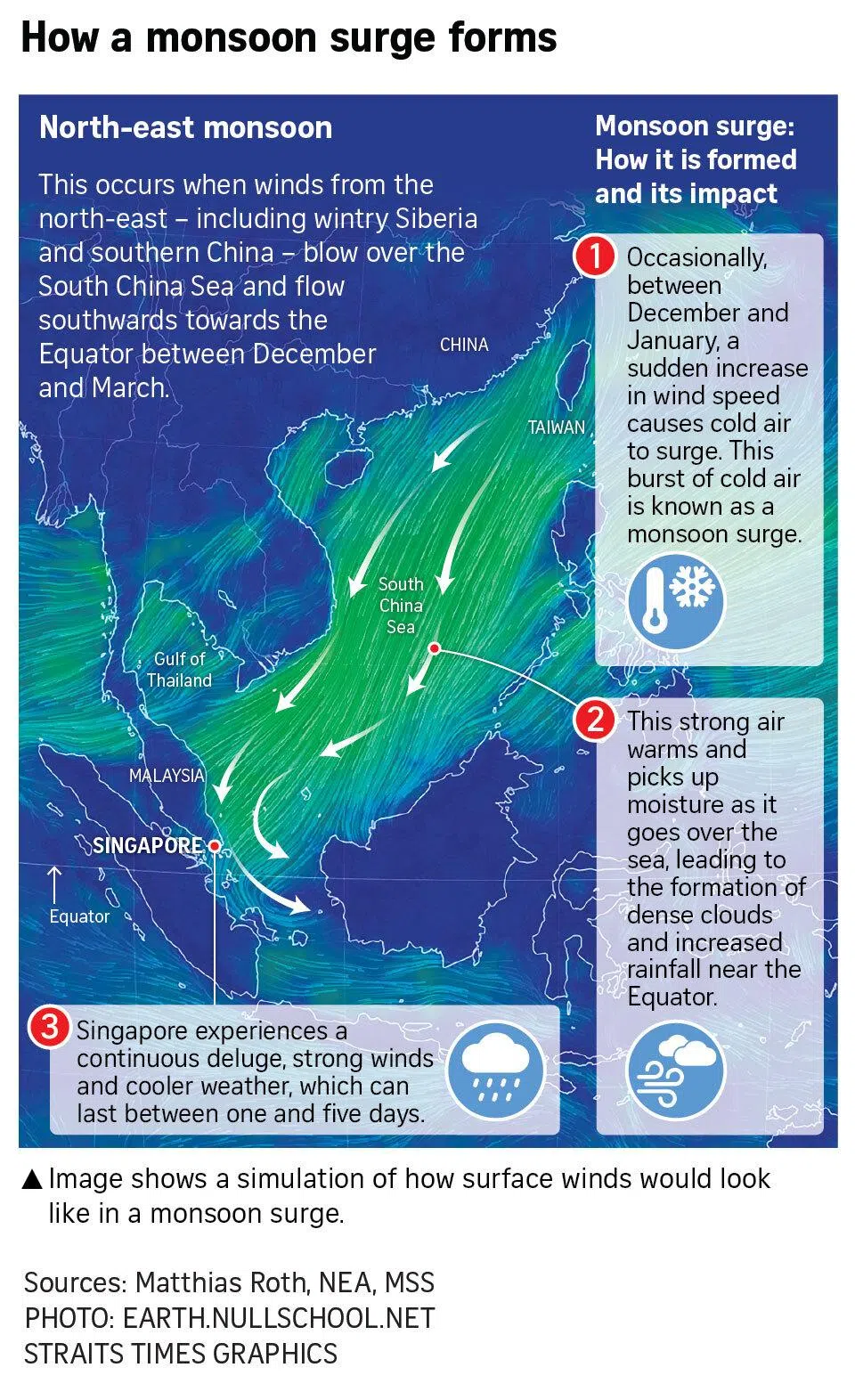

A monsoon surge usually happens in Singapore during the wet phase of the north-east monsoon season, which is in December and January.

ST PHOTO: AZMI ATHNI

- Singapore's early January 2025 non-stop rain, caused by a monsoon surge, is unlikely to repeat in the coming week, as no surge is expected.

- Monsoon surges happen during the wet phase of the north-east monsoon (Dec-Jan), bringing rainfall, strong winds, and cooler temperatures.

- The Meteorological Service Singapore uses models and observations to forecast surges, providing warnings, but intensity prediction remains a challenge.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – The non-stop rain and sweater weather Singapore experienced in early January 2025

This comes as the Malaysian Meteorological Department in late December warned of a monsoon surge descending on the country in early January 2026, with over 1,000 people evacuated in Sarawak due to worsening floods.

A monsoon surge is a weather phenomenon that usually happens in Singapore during the wet phase of the north-east monsoon season, which is in December and January.

During this period, two to four surge events typically occur. Each episode can last a few days.

The phenomenon occurs when bursts of cold, dry air from wintry regions like Central Asia move over the warm waters of the South China Sea, picking up moisture. This brings extensive rainfall, strong winds and cooler temperatures to Singapore.

The first monsoon surge of 2025 on Jan 10 led to a nearly three-hour flood in Jalan Seaview in Mountbatten. The four-day downpour delayed and diverted flights, and hit business at the Chinese New Year bazaars.

The flash flood in the coastal area occurred because high tides of up to 2.8m coincided with the prolonged intense rain from the surge. The rain that fell over Jan 10 and 11 exceeded the month’s average.

This week, high tides are also expected. ST checks on the National Environment Agency’s website showed that tides are expected to exceed 3m in the afternoons, reaching 3.3m on a couple of days. Around noon on Jan 5, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve recorded a high tide of nearly 4m.

High spring tide close to the main hide of Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve on Jan 5.

ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

But in the absence of a monsoon surge, less rain falling over the country could keep flooding at bay.

On Jan 2, the Meteorological Service Singapore (MSS) said in its fortnightly weather update that rainfall in the first half of the month is expected to be below average over most parts of the island.

An MSS spokesperson said a monsoon surge may be detected several days ahead using models that simulate the high pressure build-up over northern Asia and the stronger winds over the South China Sea.

To forecast a monsoon surge, MSS scientists rely on weather observations and computer models. The models take in current observations and solve complex equations that represent the physics of the atmosphere, MSS told ST.

During winter in the Northern Hemisphere, the chilly environment causes air over land to sink, producing high-pressure systems over Siberia and China, which periodically build up.

When this high pressure reaches a peak, it releases cold air in bursts. This sudden burst of cold air then surges over the warm South China Sea, picking up moisture as it travels.

At times near Singapore, the winds may interact with a separate whirlpool of air where winds are forced to move upwards, forming clouds. This is called a low-pressure vortex, which worsens the deluge over the country.

“As the surge gets closer, we rely increasingly on weather observations, such as from weather satellites, radar and weather stations, to monitor and track its development,” added the MSS spokesperson.

Monsoon surges are easier to forecast because they are larger in scale compared with a short-lived thunderstorm over Ang Mo Kio, for example.

Surges can thus be simulated on weather models a few days ahead and, whenever possible, warnings are given at least a day in advance.

The main challenge is in predicting whether it will be an intense or mild episode. For instance, the second surge between Jan 17 and 19 in 2025 ended up being less intense and shorter than the first

“The challenge we face is how best to communicate the advisories as there could be variations in intensity of surge events and uncertainties in the forecast,” said the MSS spokesperson.

While weather models can simulate key surge features to some extent, small shifts in their position or timing can make a big difference locally.

“For example, if the strongest winds or cloud clusters are displaced slightly north or south of Singapore, we may experience only passing showers, instead of widespread continuous rain,” said the spokesperson.

Sometimes Singapore experiences fair weather, while neighbouring Malaysia is affected by monsoon surges that worsen floods there. Where the phenomenon occurs depends on where the strongest winds are blowing, said the spokesperson.

“North-east monsoon surges are large-scale systems which can affect areas from the northern part of Peninsular Malaysia all the way to Singapore. The main part of the surge does not always happen over the same location,” MSS explained.

For example, at times, especially at the early stage of the monsoon in November, the strongest winds are steered towards the northern part of Peninsular Malaysia.

“This leads to widespread continuous rainfall along Malaysia’s east coast but does not affect Singapore,” MSS said.