Singapore researchers develop antibiotics alternative for cow udder infection

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

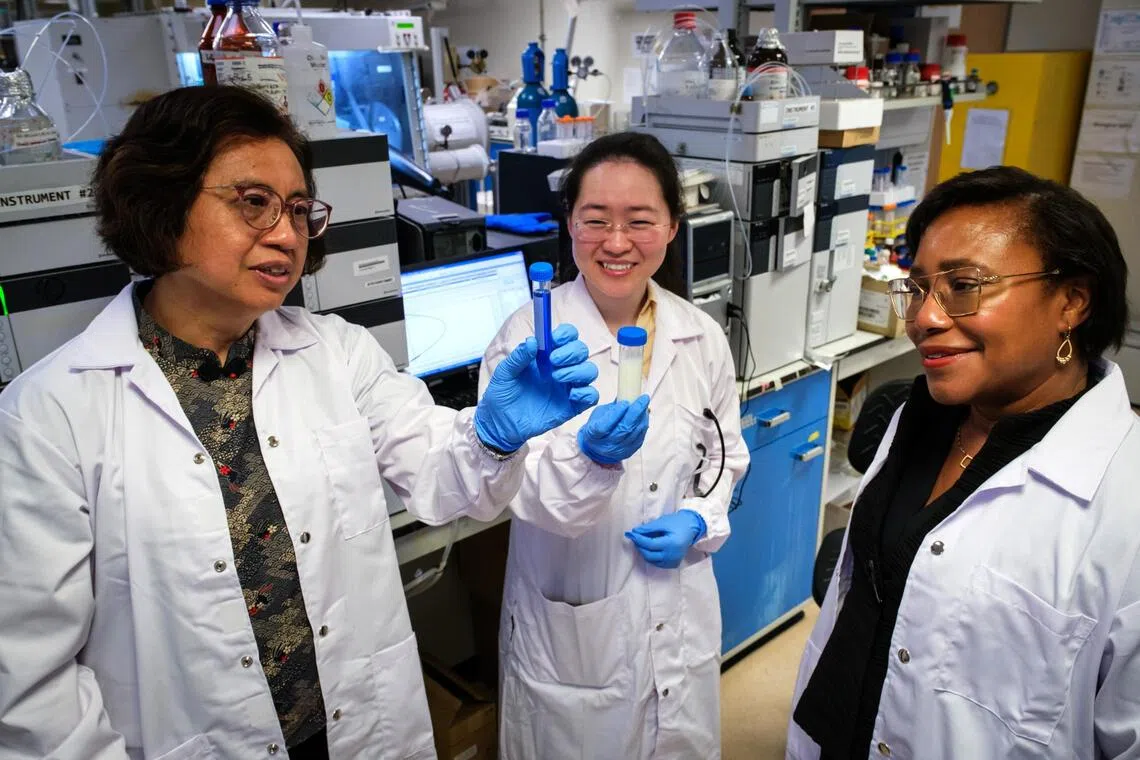

(From left) Professor Mary Chan from NTU, Dr Zhang Kaixi from the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology and Prof Paula Hammond from MIT.

PHOTO: NTU

SINGAPORE – New antimicrobial compounds developed in Singapore could help treat a bacterial infection of cow udders that significantly reduces milk output and causes global losses to the tune of billions each year.

The compounds could act as an alternative to antibiotic usage, which has raised concerns about rising antibiotic resistance and milk contamination from antibiotic residues.

This breakthrough was developed by an antimicrobial resistance (AMR) interdisciplinary research group comprising researchers from Nanyang Technological University (NTU) and the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (Smart). Smart is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) research enterprise in Singapore.

Bovine mastitis is an inflammation of the mammary gland in cows, caused by microbes entering the teat via the teat canal.

This typically occurs because the cow’s teat canal is open for about 30 minutes to 45 minutes after milking, which leaves it susceptible to infection, said Dr Zhang Kaixi, a research scientist with Smart’s AMR research group.

To prevent infection, cow’s udders are typically dipped in an antiseptic solution, such as those containing iodine or chlorhexidine, she added.

However, the long-term use of these solutions can irritate udders or cause their skin to crack, which increases the risk of infection, she said.

Antibiotics are usually used to treat cow’s udders when they are infected. However, this results in high concentrations of antibiotics in the milk during the treatment period, which can last up to 11 days.

Such milk cannot be consumed or sold under current regulations, Dr Zhang noted, adding that bacteria resistant to such antibiotic treatments have surfaced.

There are also concerns that after cleaning the udders of the antiseptics, iodine and chlorhexidine may find their way into the environment, which could result in issues such as causing harm to aquatic life.

The researchers found that novel compounds called oligoimidazolium carbon acids, or OIMs, could be used to tackle these challenges, with their findings published in the scientific journal Nature Communications in July 2025.

The OIMs were developed with the aim of creating new antimicrobial polymers for use in both the agricultural and biomedical fields to fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria, said Professor Mary Chan, one of the co-leads for the research, who is from NTU’s School of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology.

Parts of the OIMs convert into highly reactive molecules known as carbenes, which allows them to slip past the bacteria’s protective membranes to damage their DNA and kill them.

As this method is more potent than typical cationic antimicrobials – which kill microbes by disrupting their cell membranes – lower doses of OIMs are needed, reducing the risk of side effects.

The compounds had previously demonstrated effectiveness in killing bacteria resistant to multiple drugs in mice, suggesting that they could be further developed for other therapeutic applications in the biomedical field.

The researchers found that cows whose teats were dipped in the OIMs did not develop udder infection over time after being exposed to bacteria.

The compounds also do not cause irritation to the cows’ udders and are easily washed off, and have no harmful environmental side effects.

“The OIMs are biodegradable and break down into natural molecules that are neither toxic nor polluting, so we expect them to be more environmentally friendly than using iodine or chlorhexidine,” said Dr Zhang, who co-authored the study.

The OIMs did not cause any significant adverse effects in cattle, said Prof Chan, who is also a principal investigator with the Smart AMR interdisciplinary research group.

“They didn’t spoil the cows’ milk nor make it unsafe for consumption as well,” she said, describing the compounds as “promising”.

One of the cows involved in an initial farm trial on the antimicrobial compound to prevent infection in cow udders.

PHOTO: ZHANG KAIXI

While the compounds can be used on other dairy animals, the team is currently focused on their application on cows, said Dr Zhang.

A preliminary trial of the compounds was conducted at a farm in China, and a longer-term trial monitoring their safety and efficacy is ongoing at a farm in Melaka, involving about 30 to 40 cows.

“With the success of our initial study in both the laboratory and in the field, we are now planning to work closely with industry partners to scale up and do larger trials in dairy cattle, with the aim of commercialising the novel antimicrobial compounds,” said Professor Paula Hammond, institute professor and executive vice-provost at MIT and principal investigator with the Smart AMR team.

Agricultural companies in countries such as Australia, Belgium and Malaysia have already expressed interest in exploring the use of the compounds, which are expected to be commercialised via a spin-off company in the longer term.