How airplane streaks in the sky supercharge global warming

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

A contrail (condensation trail) formed from aircraft engine taken from Gardens by the Bay on Jan 12.

ST PHOTO: BENJAMIN SEETOR

- Contrails, vapour clouds from plane exhaust, contribute significantly to global warming, possibly 30-65% of aviation's impact, especially in colder regions at higher altitudes.

- Singapore's Aviation Meteorological Programme, launched in December 2025, will study contrails in the Asia-Pacific region to inform mitigation strategies and global policies.

- Rerouting flights to avoid contrail formation can reduce warming by up to 50% with minimal impact on fuel use, while sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) offers another potential solution.

AI generated

SINGAPORE - The white streaks left by planes as they zip through the skies make a pretty sight, but they can harm the planet at times.

These vapour clouds formed from planes’ engine exhaust are known as condensation trails – or contrails – and can contribute to global warming if they stay in the skies for long.

In aviation’s climate footprint, contrails are the lesser-known warming sibling of jet fuel.

The International Civil Aviation Organization warned in a 2025 report that warming caused by contrails is expected to increase over time due to the projected rise in air traffic and the expected upward shift in flight altitudes.

Singapore is also looking into contrails in the Asia-Pacific as part of a recently announced Aviation Meteorological Programme

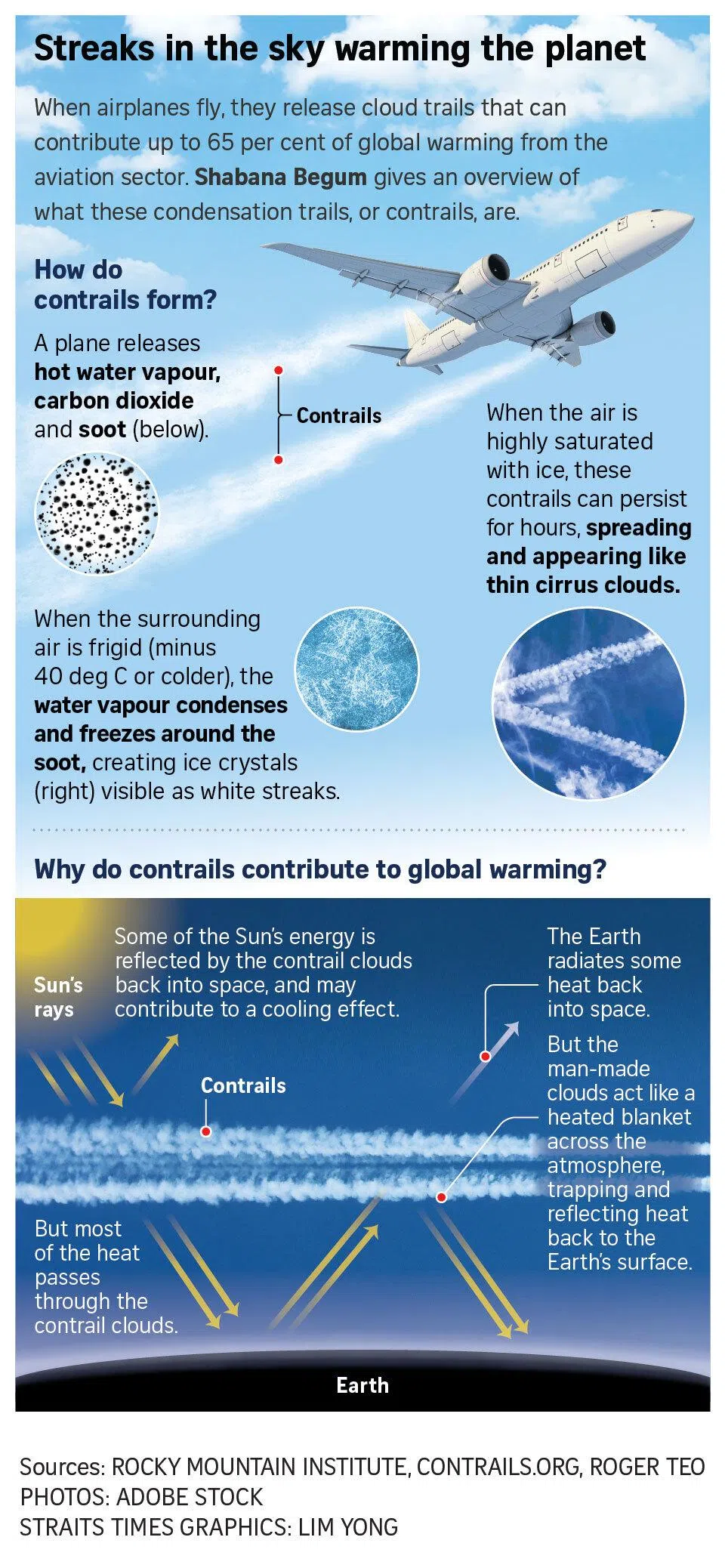

Contrails are created when hot water vapour, soot and other particles released from the plane’s exhaust mix with the frigid air at high altitudes. Water vapour condenses around the soot and freezes, creating ice crystals visible as linear clouds.

In regions super-saturated with ice, contrails can appear like thin cirrus clouds, persisting for hours. While they reflect some of the Sun’s energy back to space, they also trap and re-emit Earth’s radiation and heat, preventing them from escaping into space.

Contrails can account for 30 per cent to 65 per cent of warming caused by the aviation sector, depending on the metrics and time horizon used to calculate the impact, said Dr Roger Teoh, an honorary research fellow at Imperial College London, whose research is focused on aviation’s impact on climate change.

The effect of persistent contrails is similar to an acute fever or infection. When they persist for hours or up to a day, the result is an intense, strong warming effect, until the man-made clouds dissipate.

When planet-warming carbon dioxide (CO2) is emitted from the burning of jet fuel, the greenhouse gas stays in the atmosphere for hundreds to thousands of years, Dr Teoh said. CO2’s warming effect is gradual and consistent, much like a chronic disease.

“If you were to compare the total warming caused by CO2 with contrails over 20 years, the effect of contrails could be twice that of CO2. But over a 100-year horizon, CO2’s impact would be 1.5 times larger than that of contrails,” said Dr Teoh.

Not all smoky streaks lead to warming. Persistent contrails are more frequently found in colder regions in the higher latitudes of Europe and North America, and are less common in the sub-tropical regions.

“In Singapore and Malaysia, you don’t see many contrails in the sky, compared with Europe, where you can see them almost every day,” he added.

This does not mean that the issue should be overlooked in this region.

Globally, roughly a fifth of all flights form persistent contrails, and only 3 per cent of those flights are responsible for 80 per cent of the warming effect.

No persistent contrails form below 37,000 feet in the tropics, where the atmosphere is warmer.

In South-east Asia, 3.3 per cent of the flight distance in 2019 left persistent contrails, said Dr Teoh.

These contrails were most likely generated by flights that cruised above 37,000 feet, where it is colder.

Such flights typically involve larger aircraft with two passenger aisles. Short-haul regional flights involving narrower aircraft usually cruise at lower altitudes and are unlikely to produce such contrails.

According to a mapping tool by non-profit organisation Contrails.org seen on Jan 24, a number of flights form warming contrails in South-east Asia. They include a flight from Melbourne to Singapore, and another from Java to Bali in Indonesia.

Under the Aviation Meteorological Programme, which was announced in December 2025, the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore and National Environment Agency will deepen scientific knowledge on contrails in this region, where the atmospheric conditions differ from those in Europe and North America.

“Currently, there is scarce data and research on contrails in the Asia-Pacific region, compared with better studied regions such as North America, Europe, and the North Atlantic,” both agencies told The Straits Times in a joint statement.

The agencies are engaging partners to scope relevant projects related to contrails, and are hoping that the programme’s work will “help inform future mitigation strategies and contribute to global policy development”.

Currently, the most viable and scalable solution to reduce the impact of contrails is to reroute planes or adjust their altitude away from contrail-producing pockets of the atmosphere.

This requires the use of weather forecasts incorporated into flight-planning software. Flight dispatchers on the ground can then work with pilots to select routes and avoid areas in real time.

In 2024, after American Airlines rerouted 22 flights to avoid contrails, a first-of-its-kind study was published showing that those flights slashed contrail formation by 64 per cent.

Dr Teoh noted that there are a few trade-offs with rerouting, such as burning extra fuel and potentially higher overflight fees when flying over some airspaces.

But by rerouting planes, contrail-induced warming can be reduced by up to 50 per cent, and jet fuel consumption typically increases by no more than 1 per cent for a given flight, he added.

When ST asked Singapore Airlines if it has embarked on any projects to limit contrails, an airline spokesperson said the airline is unable to provide data on contrail generation or discuss specific initiatives at present, and will share more when appropriate.

Switching to sustainable aviation fuel (SAF)

By 2030, the greener fuel is expected to contribute just 2 per cent to 5 per cent of jet fuel.

Dr Teoh said: “In rerouting the flights, it can be done today. You don’t need any additional (major) infrastructure. Using SAF does not need rerouting, but there is not much supply now.”