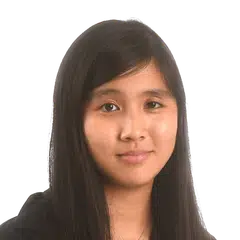

From tissue to trees: How critically endangered plant species are lab-grown in Singapore

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

A native plant generated from tissue at Temasek LifeSciences Laboratory in a photo taken on Aug 8.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

Follow topic:

- Singapore uses tissue culture to propagate critically endangered trees, overcoming seed viability and seasonal challenges.

- The process involves sterilising tissue, multiplying it in labs, and acclimatising the lab grown plants.

- This technique gives rare species a fighting chance, say ecologists.

AI generated

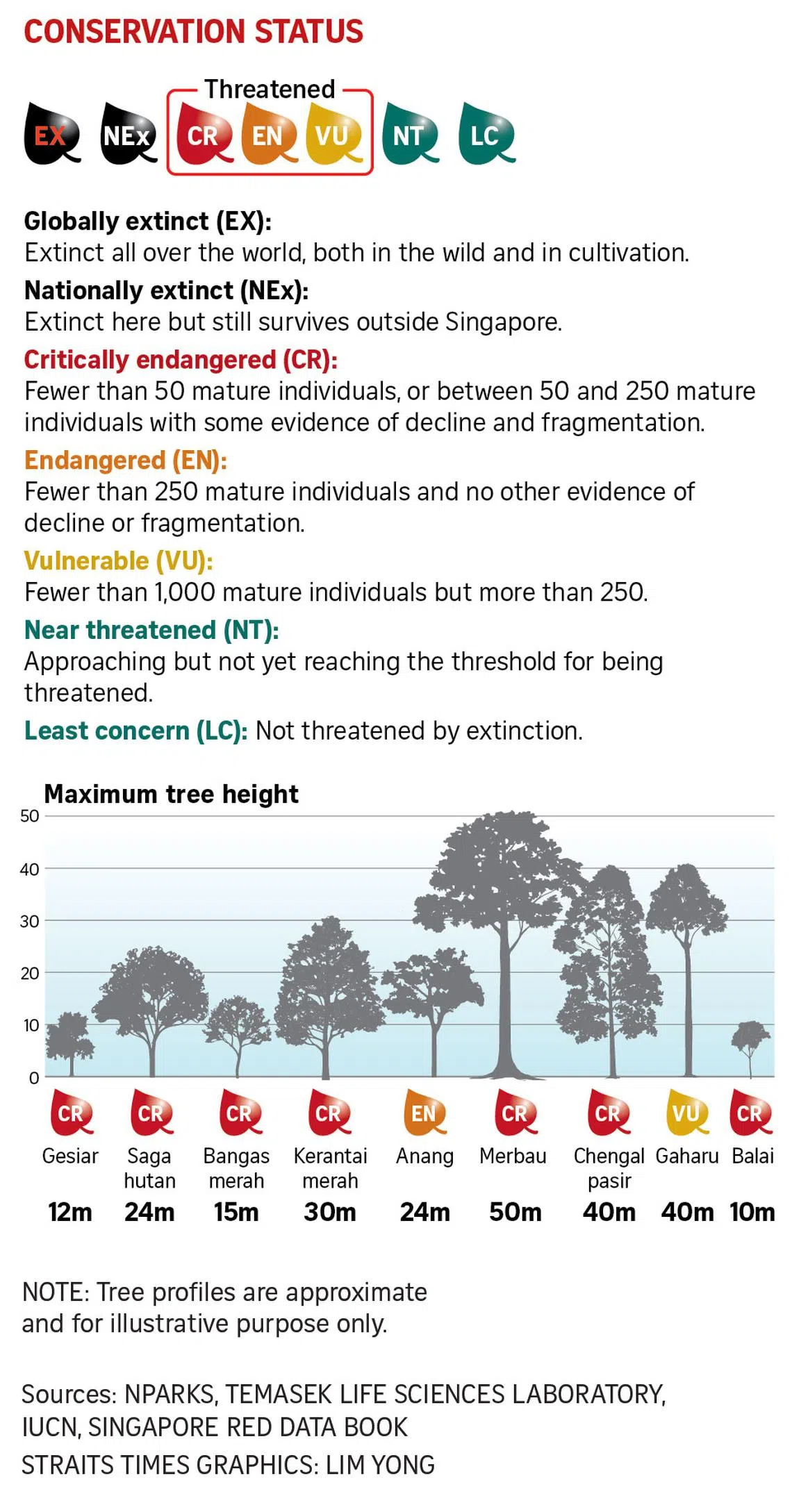

SINGAPORE – In a nondescript building in Kent Ridge, botanists have cracked the code to mass produce clones of critically endangered trees here to aid their fight against extinction.

At the heart of their effort are stem cells extracted from the native trees, which are sterilised and placed in nutrient-rich solutions to spur their transformation from tissue to tree.

Building on the decades-old technique of plant tissue culture, scientists at Temasek LifeSciences Laboratory have developed specialised protocols to propagate tissue from nine species of native trees

The laboratory’s assistant director of plant transformation and tissue culture, Dr Somika Bhatnagar, said the Singapore Endangered Native Tree Project plugs the gaps where growing from seed and conventional propagation methods like stem cuttings are too slow or difficult to save species on the brink.

Asia’s tropical forests can go without flowering or fruiting for many years, making it challenging for conservationists to track and harvest their seeds.

The race against the clock is especially urgent for Singapore’s critically endangered trees, which number fewer than 50 mature individuals in the wild.

“Sometimes, even these seeds may have low viability,” said Dr Somika, a plant molecular biologist who has been researching trees for more than two decades.

Surrounded by stacks of baby plants encased in culture vessels, she said: “Precision tissue culture allows limited or damaged specimens to be rescued and ensures that the genetic lines of these rare trees are preserved.”

It was tricky, however, to build tissue culture protocols for each species from scratch, as the parent plants are aged or had limited healthy material for cultivating the trees, said Dr Somika. On occasion, the tissue had to be retrieved by climbers.

She added: “Most of the time, bacteria and fungus were present both outside and inside the tree, or were undetectable from the surface. So we would take a long time to sterilise the tissue because without sterilisation, they will not establish (uncontaminated) cultures for multiplication.”

Only a low percentage of the collected tissue survived the first step of the process.

The researchers had to find the best supplements and conditions that optimised the growth of each species, noted Dr Somika.

Despite the odds, every fragment was instrumental to creating an effective protocol.

Said Dr Somika: “With tissue culture, we just need a very small part of a plant (containing stem cells) that can be readily found throughout the year. We do not depend on the season, the environment or the maturity of the tree, which can take years.”

While a single seed can yield only a lone tree, tissue culture can produce a “limitless” number of genetic carbon copies from one plant, she added.

She said the progeny cultivated from multiple trees ensures a diverse gene pool. Such diversity ensures that the cultured trees are less susceptible to being devastated by pests and diseases.

They are the product of a joint effort by labs run by Dr Somika and Dr Ramachandran Srinivasan at Temasek LifeSciences Laboratory and the National Parks Board (NParks), in partnership with Temasek Foundation.

Dr Somika Bhatnagar on Aug 8 examining tissue cultured plants at Temasek LifeSciences Laboratory in Kent Ridge.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

The species were handpicked for their ecological function, cultural importance or conservation urgency.

The trees include Malaysia’s national tree, the merbau (Intsia palembanica), and the historic chengal pasir tree (Hopea sangal) that sparked awareness for heritage tree conservation here.

By the time the project concluded at the end of 2024, the lab had spawned “multiple” tissue-cultured plantlets over three years, she added, declining to share exact figures.

They were fed specialised nutrient media formulated precisely for each stage of growth, and stowed in controlled conditions in a negative-pressure room that flushed out harmful microbes.

Said Dr Somika: “We have a different recipe for each stage of development. It’s like different diets required by babies, toddlers, teenagers and adults.”

A native plantlet cultivated at Temasek LifeSciences Laboratory that has generated roots and leaves.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

While tissue cultured under the lab’s plantation and forestry programmes can take as fast as two months to morph into a baby plant, the chosen trees took as long as a year.

The lab-grown plantlets were given about two to six months to acclimatise to outdoor weather and soil in a greenhouse, after which they were delivered to NParks.

Mr Ang Wee Foong, NParks’ director of horticulture excellence and nursery management, said the lab specimens are nurtured in the board’s nursery, and will be planted in suitable habitats for them if they reach suitable height and form.

He added: “We will test the protocols in our laboratory to see if they can be used to sustainably propagate more of the species.”

Already, 10 gesiar trees (Paranephelium macrophyllum) from the project have been introduced to the outdoors, with the first mass-planting event on July 29 at the Rail Corridor.

Like a proud mother, Dr Somika beamed as she showed this reporter a photo of her with a petri dish and a bottled plant next to a 3m-tall sapling during the planting.

She said: “For me, cultivating trees is about making a lasting impact and leaving behind a legacy.”

“So even when we are gone, our natural heritage will still be there for future generations.”

Native trees being acclimatised to Singapore’s climate at a greenhouse in Temasek LifeSciences Laboratory on Aug 8.

PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

NUS Assistant Professor Lim Jun Ying, who studies the ecology of tropical forests, said the tissue-cultured trees will give their species “a fighting chance” through a boost in numbers, although they do not solve the issue of low genetic diversity that plagues rare trees.

Veteran conservationist and senior lecturer at NTU’s Asia School of Environment Shawn Lum said the technique will be useful for Singapore’s undisturbed forests, where seed production is not assured as the habitat exists in small fragmented patches.

He said: “Some species can be successfully grown from rooted stem cuttings, but some plants, especially woody ones, can be extremely stubborn and do not readily form roots from the ends of cut stems.”

Lauding the project, Dr Lum called for a greater integration of the organisations’ facilities and skills, which would align plant research and forest monitoring to identify at-risk species and those that require plant propagation work, including tissue culture.

He added: “With Singapore having an inordinately high lightning strike rate, any forest giant has a chance of being an unlucky victim, and tissue culture provides insurance against the loss of rare individuals before their next flowering event.”

The species

Gesiar (Paranephelium macrophyllum)

Its scientific name references the tree’s large leaf blades up to 35cm long. When in bloom, the tree is decked with bristle-like clusters of red, pink and white flowers.

It can be cultivated for ornamental foliage, timber, seed oil for lamps and treating skin diseases.

Saga hutan (Ormosia bancana)

The seed of the Ormosia bancana tree.

PHOTO: ANG WEE FOONG, NPARKS

The tree’s scientific name means “necklace from Indonesia’s Bangka Island”, one of the places where the tree can be found. It grows in Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Mandai Forest, Nee Soon Swamp Forest and near MacRitchie Reservoir.

It is a nitrogen-fixing plant. It can also be used for timber, and its seeds have been turned into jewellery.

Bangas merah (Memecylon garcinioides)

Flowers of the Memecylon garcinioides tree.

PHOTO: ANG WEE FOONG, NPARKS

Its scientific name is derived from its similarities with two other kinds of trees. When in bloom, it is dotted with white-bluish blossoms.

The tree has been used for wooden products like walking sticks. It also feeds birds with its fruit.

Kerantai merah (Ellipanthus tomentosus)

Its scientific name references the hairs on the tree’s leaves. The flowers have a strong, sweet scent.

The tree is a nectar source for fauna.

Anang (Osmelia grandistipulata)

Its scientific name alludes to the fragrance of honey, most likely from the tree’s flowers. It is found in the low-altitude forests of Borneo, Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra.

The tree has been used for timber and wooden products, such as building materials and chairs.

Merbau (Intsia palembanica)

It was chosen as Malaysia’s national tree in 2019 for its hardiness and height. Its scientific name references Palembang in Indonesia, where it can be found.

The tree has many uses, which range from being a source of food to producing dyes.

Chengal pasir (Hopea sangal)

A Hopea sangal tree in the Changi area.

PHOTO: NATURE SOCIETY SINGAPORE

Its scientific name commemorates the first royal keeper of Edinburgh’s Royal Botanic Garden, John Hope. Nature enthusiasts believe that Changi is christened after the tree.

The tree has been used for timber.

Gaharu (Aquilaria malaccensis)

Aquilaria malaccensis fruit and seeds.

PHOTO: ANG WEE FOONG, NPARKS

Its scientific name is derived from the Latin word for “eagle”, after the tree’s common name in Melaka – eaglewood. Because of demand for its highly valuable resin, the tree is critically endangered worldwide.

The tree produces agarwood, which is popular for fragrances and medicine.

Balai (Aralidium pinnatifidum)

Its scientific name is a nod to its feather-like lobed leaves. It can be found in Peninsular Thailand, Borneo, Malaysia and Sumatra.

The tree has been used in traditional medicine to treat conditions like fever and kidney diseases. It has also been used for timber.

Correction note: In an earlier of version of the story, we misspelled Mr Ang’s name. We are sorry for the error.