From spiky branches to dome-shaped: How corals in Singapore have evolved over 70 years

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

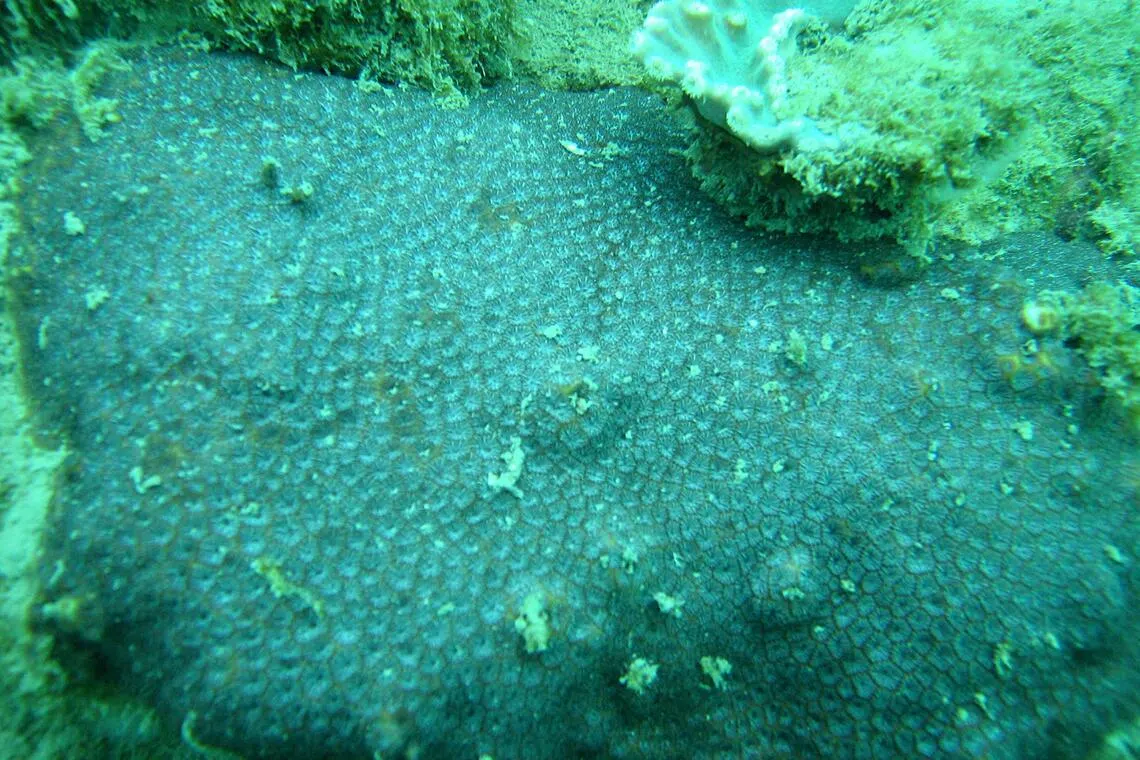

The corals today are mostly dome-shaped or flat and they host a lower diversity of marine life.

PHOTOS: HUANG DANWEI, NPARKS

- Singapore lost 65% of coral reefs since the 1960s due to coastal development. Remaining reefs are now dominated by dome-shaped corals.

- A 70-year study reveals declining ecological functions in reefs, with sensitive branching corals decreasing and some, like birdsnest coral, locally extinct.

- To restore reefs, NParks supports research towards suitable coral species for specific conditions, alongside improving water quality and sedimentation control.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – As more than two-thirds of Singapore’s coral reefs have been lost to coastal development and reclamation since the 1960s, the characteristics of its remaining reefs have changed dramatically over the decades.

For one thing, there are fewer fast-growing and branching corals now, which means fewer marine animals are able to seek shelter within the reefs.

Coral species dominating the remaining 10 sq km stretches of reefs are mostly dome-shaped or flat, and they are expected to host a lower diversity of marine life, said marine biologist Huang Danwei, deputy head of the NUS Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.

However, these species tend to be more adaptable and tolerant of stressors like heated up waters, he added.

The declining ecological roles of Singapore’s reefs were a key finding of the first study that tracked the species and functions of the island-state’s coral reefs since the 1950s.

This study was published in a new book, Coral Reefs Of Singapore’s Urbanised Sea, released in October.

The over 230-page tome – edited by Associate Professor Huang and Emeritus Professor Chou Loke Ming from the NUS Department of Biological Sciences – documents how reefs respond to decades of urbanisation impacts and marine heatwave episodes caused by climate change.

Understanding the reefs’ past could offer glimpses into the future, especially as the Republic recently embarked on a 10-year effort to plant 100,000 corals in its waters – its largest coral restoration effort to date.

Most of Singapore’s intact reefs are in the Southern Islands. The island-state is home to around 250 species of hard corals, a third of the world’s coral species. More than 200 species of sea sponges and 120 species of reef fish, including rare seahorses, rely on the reefs for shelter and food and to rear their young.

Sea sponges, often mistaken for plants, are colourful aquatic animals with dense, porous skeletons.

The book’s authors have described Singapore’s reef environment as “extreme”. Decades of extensive land reclamation, coastal development and regular dredging of shipping channels in the region have caused the waters to be murky and sedimented.

Since 1997, the reefs have also been struck by four global coral bleaching events, with the most recent one in 2024 killing about 5 per cent of local corals.

Corals get their vibrant colours from microscopic algae living in their tissues. When stressed by warmer waters, the corals expel the algae and turn ashen white in a phenomenon known as coral bleaching.

After the massive coral losses in the 2024 coral bleaching episode, scientists here are expecting the ecological functions of the reefs to be depressed over the next few years, said Prof Huang.

While intricately shaped and branching corals like the acropora are fast-growing, they are most sensitive to environmental stress, and their numbers have declined significantly over the years, he added.

Stress-tolerant species like the brain coral have persevered, filling the space left by the dying branching corals.

“Species that grow and colonise the reef environment quickly, and thus can help facilitate recovery during times of stress, have also declined,” said Prof Huang, citing the spiky, thin bird’s nest coral that was declared locally extinct in 2024.

In October, a global report by 160 scientists declared that the planet is facing its first catastrophic tipping point due to global warming, with warm-water coral reefs at risk of dying out.

Prof Huang and his team are hoping that the findings from tracking the reefs over 70 years will lead to smarter ways of restoring the habitats.

These findings could help coral planting programmes identify the species that would be most suitable for specific reef conditions, said Ms Denise McIntyre, the study’s lead researcher and a recent life sciences graduate from the National University of Singapore.

She noted that the National Parks Board has been supporting research to increase the fit of corals on restored reefs.

“For example, at a site with mostly loose coral rubble, restoration could prioritise species that are fast-growing, encrusting and binding rubble pieces together, so that the reef environment can be physically stabilised, allowing other species to take hold,” she said.

But for branching corals to make a comeback, water quality must be improved and sedimentation controlled, she added.

This includes relocating corals that will be exposed to sediment plumes from reclamation and putting up silt barriers to trap sand, preventing it from dispersing into the surrounding environment.

Another solution that goes a long way is conserving and restoring natural habitats, so that filter-feeding marine creatures like mussels and sponges can absorb and break down pollutants and excess nutrients into less harmful substances, said Prof Huang.

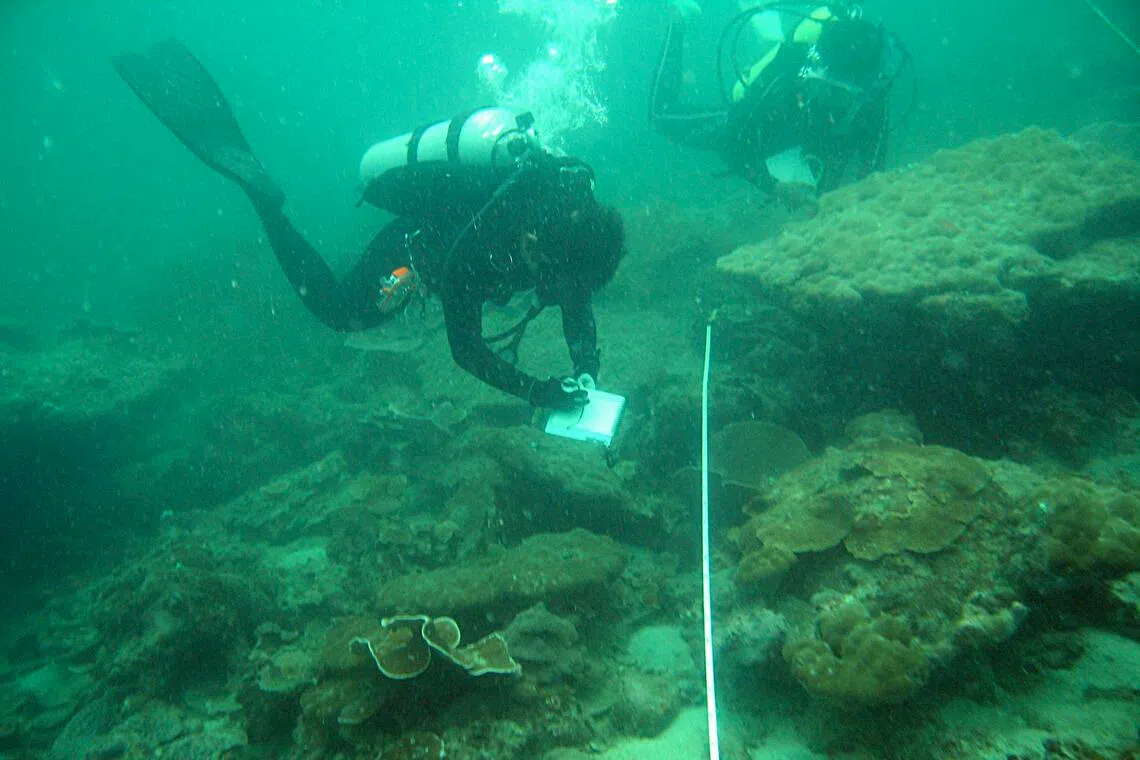

To dive into decades of reef history, Ms McIntyre and her team studied data from coral specimens donated to the museum, and field surveys at the reefs of Pulau Hantu and Pulau Satumu, where Raffles Lighthouse is located. A total of 257 hard coral species were recorded.

Researchers from the National University of Singapore doing a reef survey in Singapore waters.

PHOTO: HUANG DANWEI

Researchers could glean insight into what Singapore’s reefs looked like from the 1950s, as the museum recently received a donation of thousands of coral specimens from South-east Asian reefs collected between the 1950s and 1970s. The donation was from Dr Chuang Shou Hwa, the head of zoology at the former University of Singapore in the 1970s.

Prof Huang said the fact that coral bleaching is occurring at higher frequencies today suggests that stress-tolerant corals may not find any safe zones.

He cautioned: “Such species have also bleached recently due to marine heatwaves, so their persistence cannot be taken for granted. The data from the past 70 years has (shown) that functional and species richness can recover if environmental conditions improve, but they can certainly decline if sedimentation is not controlled and climate change not addressed.”

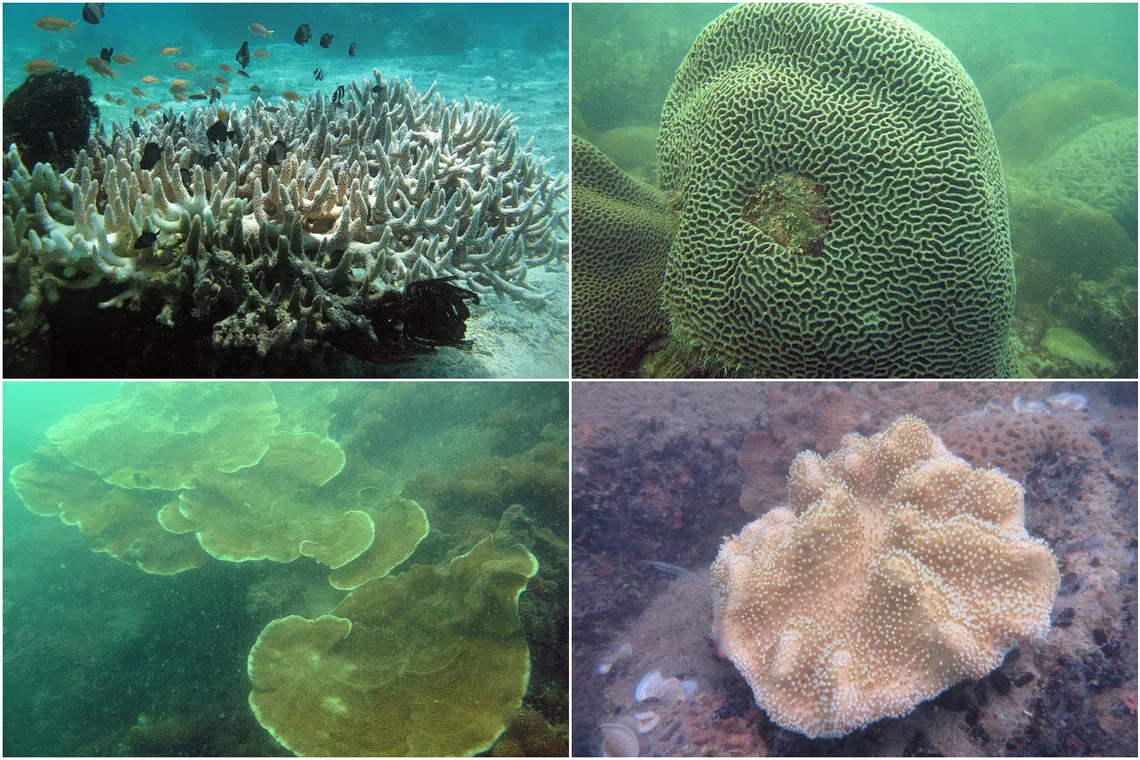

Shapes of Singapore’s reefs

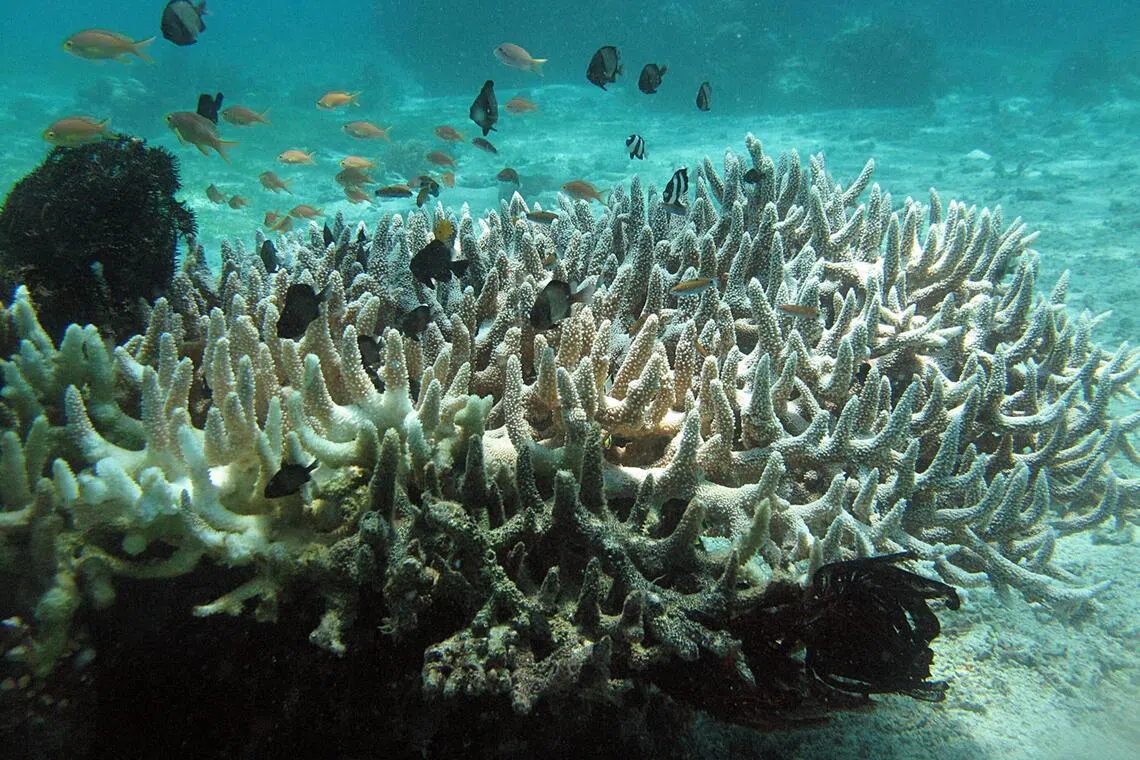

Branching

Branching corals, such as the staghorn coral, tend to be competitive, overtopping other corals in the fight for space.

PHOTO: HUANG DANWEI

Branching corals are fast-growing and among the types planted for reef restoration worldwide.

They tend to be competitive, overtopping other corals in the fight for space.

The corals’ structure provides tiny habitats for reef dwellers like crabs, shrimp and fish.

The corals are sensitive to environmental stressors, including warmer waters and sediments.

Boulder-shaped

Brain corals grow slowly and often divert energy to storage to help sustain them during stressful times.

PHOTO: HUANG DANWEI

These corals tend to be more tolerant to stressors like warmer waters and higher salinity, partly because they tend to rely less on their microscopic algae for energy needs.

They grow slowly and often divert energy to storage to help sustain them during stressful times.

These ball-shaped coral types tend to be found along seawalls, suggesting that man-made structures favour the establishment of stress-tolerant species.

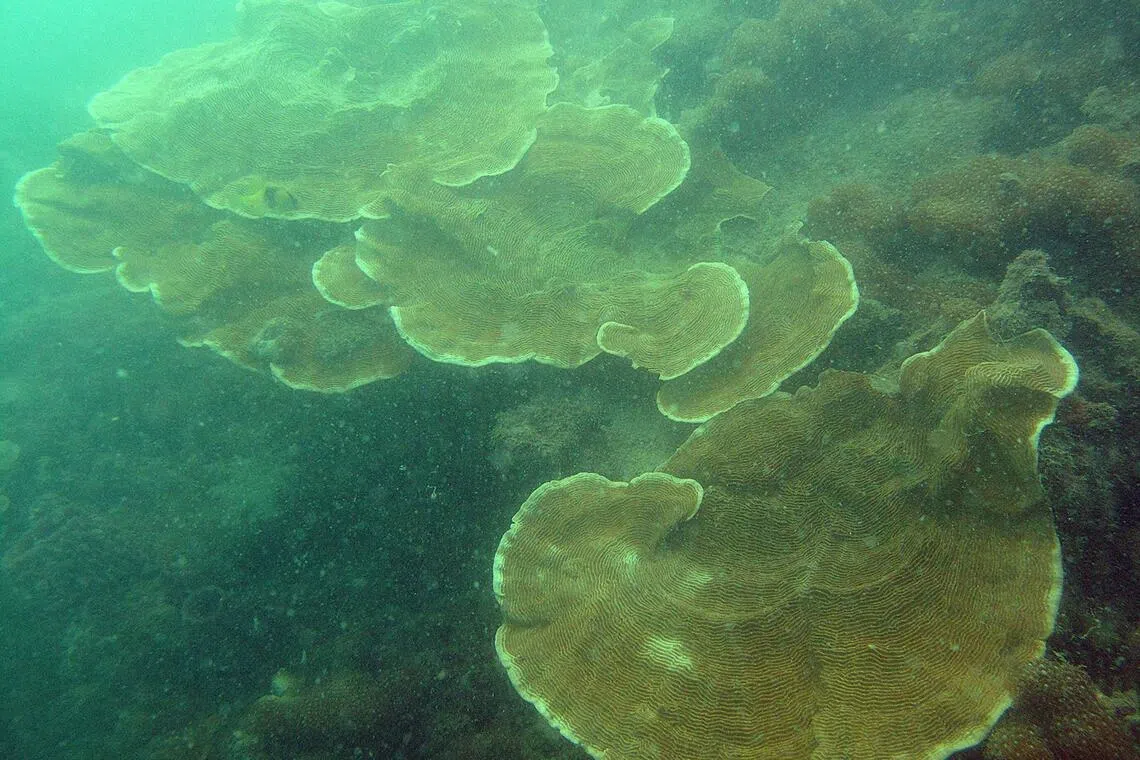

Plate-like

Ringed plate corals tend to host a large number of reef animals with their wide structure.

PHOTO: HUANG DANWEI

Plate-like corals can thrive in a range of environmental conditions, especially in the deepest parts of the reef, as their large spreading plates help capture sunlight.

The corals tend to host a large number of reef animals with their wide structure.

Encrusting

Crust corals can withstand strong waves better than branching corals, which can snap.

PHOTO: HUANG DANWEI

They tend to form a layer of crust over a rocky surface.

Such corals act as a natural “cement”, binding loose reef components together.

They can withstand strong waves better than branching corals, which can snap.

Soft coral

Lobophytum leather corals serve as habitats for tiny animals like brittle stars and shrimps.

PHOTO: NPARKS

Soft corals can resemble undersea flowers, fans or leathery beds.

While they are not reef builders like hard corals, they serve as habitats for tiny animals like brittle stars and shrimps.