As Aceh reels from severe floods, NTU-led study in 2024 traces roots to forest loss

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Researchers found that more than 2,000 flood events happened in Aceh between 2011 and 2018.

PHOTO: AFP

- Deforestation in Aceh, Indonesia, exacerbates monsoon floods, as highlighted by the devastating floods of November 2025 which killed over 1,000 people.

- An NTU study led by Dr Lubis (PLOS One) found flood-prone Aceh areas had fewer trees, more palm oil, and higher poverty, with over 2,000 floods between 2011-2018.

- Dr Lubis suggests conditional cash transfers linked to forest restoration can aid recovery and reduce future flood risk; Indonesia plans to revoke forestry permits.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – While land clearing for plantations in Indonesia has been blamed for causing haze, deforestation’s role in fuelling floods has received far less attention.

That changed after devastating monsoon floods in November, worsened by a rare cyclone,

Environmentalists have blamed deforestation for aggravating the damage

Led by researchers from the NTU Asian School of the Environment, the study found that flood-prone areas in Aceh were likely to have fewer trees, more oil palm plantations and higher poverty rates.

By extracting data from primarily online news reports, the researchers found that more than 2,000 flood events happened in Aceh between 2011 and 2018.

Overall, the number of floods steadily increased each year, displacing around 158,000 people, as well as damaging about 24,500 houses and 11,500ha of agricultural land.

The impacts of the 2025 floods largely reflect the patterns identified in the 2024 study, said Dr Muhammad Irfansyah Lubis, lead author of the study, which was published in scientific journal PLOS One. The study was conducted by Dr Muhammad Lubis and another researcher, both affiliated with the NTU Asian School of the Environment and the Earth Observatory of Singapore, along with a third researcher from the Wildlife Conservation Society.

“Many of the (currently affected areas) overlap with areas previously identified as having low tree cover, extensive land conversion, higher poverty rates and recurrent flooding,” said Dr Muhammad Lubis, who is now working at the National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia.

Flood impacts were most severe in places already degraded by deforestation and the expansion of plantations, particularly oil palm. Several heavily affected districts, including Aceh Singkil, also have persistently high poverty levels, he added.

As at Dec 2, Aceh Singkil recorded more than 6,100 affected households, the highest in all districts, according to humanitarian organisation Human Initiative.

Aceh has the largest area of intact forest on the island of Sumatra, but it has been threatened by development, illegal logging and conversion to agricultural land.

The province is part of the Leuser forest ecosystem – the last place on earth where endangered species like Sumatran orangutans, tigers, elephants, and rhinoceroses roam the same land.

Carbon-rich peatlands on Aceh helped to minimise the impact of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami on coastal communities, stated the paper.

In 1971, forest covered 75 per cent of the province. But between 1990 and 2000, more than 30,900ha of forests were cleared each year.

Large forest areas in Aceh Singkil have been replaced by oil palm, and these lands are now increasingly threatened by more frequent flooding during the rainy season, added the paper.

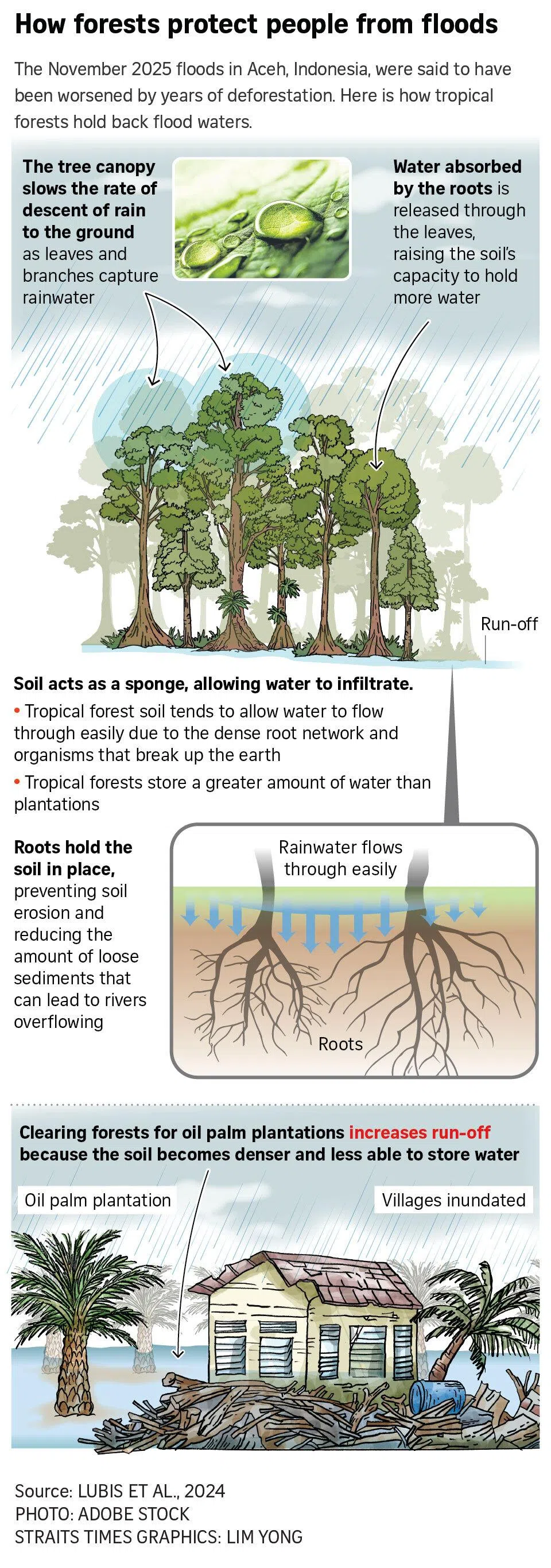

Soil in oil palm plantations is denser and tightly packed, reducing the ability of flood waters to seep through. This, in turn, increases run-off and land erosion.

In contrast, tropical forests allow flood waters to seep into the ground through complex root systems and soil organisms, enabling forests to store greater amounts of water than agricultural or urban areas.

There were reports of piles of logs swept away in the November floods, potentially exposing illegal logging.

“Our findings highlight the critical link between forest preservation and flood prevention, and the irreplaceable role that forests play in ensuring the well-being of local communities, especially those affected by poverty,” stated the paper.

While the importance of forests in reducing flooding is clear, the scientific evidence has had little influence in changing flood management policies.

One reason is that on the field, it is hard to directly attribute flood incidents to forest loss, noted Dr Muhammad Lubis. There are other factors at play, such as terrain, climate, land use and population density.

“The key task now is to build robust and accessible evidence demonstrating that forest degradation – particularly driven by extractive industries and land-use change – has been a contributing cause of increased flood risk,” he added.

In late December, The New York Times reported that Indonesia’s Ministry of Forestry had identified “indications of violations” by 12 companies in North Sumatra, and plans to revoke about 20 forestry permits covering 750,000ha.

However, the government’s slow response in providing aid to flood and landslide victims had sparked protests in Aceh.

Dr Muhammad Lubis said: “The 2025 floods have severely damaged the main livelihoods of many communities, making immediate financial support essential to helping families meet basic needs and recover.”

In the short term, conditional cash transfer schemes can provide quick assistance to affected families while reducing the need for harmful coping strategies, such as further forest clearing, he suggested.

Such schemes involve the authorities giving money to families in need, on the condition that they meet certain education or health obligations to escape the poverty cycle.

The financial support should also act as a pathway towards more sustainable livelihoods, he pointed out.

Dr Muhammad Lubis said: “By linking financial assistance to activities such as forest restoration, agroforestry and watershed protection, communities can rebuild income while lowering future flood risks.”